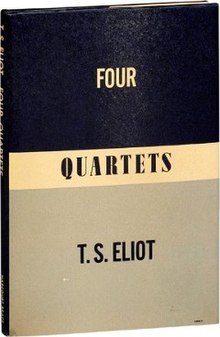

Four Quartets |

| Author | T. S. Eliot |

|---|

| Language | English |

|---|

| Genre | Poetry |

|---|

| Publisher | Harcourt (US) |

|---|

Publication date | 1943 |

|---|

| Media type | Print |

|---|

| Pages | 40 |

|---|

Four Quartets is a set of four poems written by T. S. Eliot that were published over a six-year period. The first poem, Burnt Norton, was published with a collection of his early works (1936's Collected Poems 1909–1935). After a few years, Eliot composed the other three poems, East Coker, The Dry Salvages, and Little Gidding, which were written during World War II and the air-raids on Great Britain. They were first published as a series by Faber and Faber in Great Britain between 1940 and 1942 towards the end of Eliot's poetic career (East Coker in September 1940, Burnt Norton in February 1941, The Dry Salvages in September 1941 and Little Gidding in 1942). The poems were not collected [as one piece] until Eliot's New York publisher printed them together in 1943.

Four Quartets are four interlinked meditations with the common theme being man's relationship with time, the universe, and the divine. In describing his understanding of the divine within the poems, Eliot blends his Anglo-Catholicism with mystical, philosophical and poetic works from both Eastern and Western religious and cultural traditions, with references to the Bhagavad-Gita and the Pre-Socratics as well as St. John of the Cross and Julian of Norwich.

Although many critics find the Four Quartets to be Eliot's last great work, some of Eliot's contemporary critics, including George Orwell, were dissatisfied with Eliot's overt religiosity. Orwell believed this was not a worthy topic to write about and a failing compared to his earlier work. [1] Later critics disagreed with Orwell's claims about the poems and argued instead that the religious themes made the poem stronger. Overall, reviews of the poem within Great Britain were favourable while reviews in the United States were split between those who liked Eliot's later style and others who felt he had abandoned positive aspects of his earlier poetry.

Background

While working on his play Murder in the Cathedral, Eliot came up with the idea for a poem that was structured similarly to The Waste Land.[2] The resulting poem, Burnt Norton, named after a manor house, was published in Eliot's 1936 edition of Collected Poems 1909–1935.[3] Eliot decided to create another poem similar to Burnt Norton but with a different location in mind. This second poem, East Coker, was finished and published by Easter 1940.[4] (Eliot visited East Coker in Somerset in 1937, and his ashes now repose there at St Michael and All Angels' Church.)[4]

As Eliot was finishing his second poem, World War II began to disrupt his life and he spent more time lecturing across Great Britain and helping out during the war when he could. It was during this time that Eliot began working on The Dry Salvages, the third poem, which was put together near the end of 1940.[5] This poem was published in February 1941 and Eliot immediately began to plot out his fourth poem, Little Gidding. Eliot's health declined and he stayed in Shamley Green to recuperate. His illness and the war disrupted his ability to write and he became dissatisfied with each draft. He believed that the problem with the poem was with himself and that he had started the poem too soon and written it too quickly. By September 1941, he stopped writing and focused on his lecturing. It was not until September 1942 that Eliot finished the last poem and it was finally published.[6]

While writing East Coker Eliot thought of creating a "quartet" of poems that would reflect the idea of the four elements and, loosely, the four seasons.[7] As the first four parts of The Waste Land have each been associated with one of the four classical elements so has each of the constituent poems of Four Quartets: air (BN), earth (EC), water (DS), and fire (LG). However, there is little support for the poems matching with individual seasons.[8] Eliot described what he meant by "quartet" in a 3 September 1942 letter to John Hayward:

... these poems are all in a particular set form which I have elaborated, and the word "quartet" does seem to me to start people on the right track for understanding them ("sonata" in any case is too musical). It suggests to me the notion of making a poem by weaving in together three or four superficially unrelated themes: the "poem" being the degree of success in making a new whole out of them.[9]

The four poems comprising Four Quartets were first published together as a collection in New York in 1943 and then London in 1944.[10] The original title was supposed to be the Kensington Quartets after his time in Kensington.[11] The poems were kept as a separate entity in the United States until they were collected in 1952 as Eliot's Complete Poems and Plays, and in the United Kingdom until 1963 as part of Eliot's Complete Poems 1909–62. The delay in collecting the Four Quartets with the rest of Eliot's poetry separated them from his other work, even though they were the result of a development from his earlier poems.[12]

World War II

The outbreak of World War II, in 1939, pushed Eliot further into the belief that there was something worth defending in society and that Germany had to be stopped. There is little mention of the war in Eliot's writing except in a few pieces, like "Defence of the Islands". The war became central to Little Gidding as Eliot added in aspects of his own experience while serving as a watchman at the Faber building during the London blitz. The Four Quartets were favoured as giving hope during the war and also for a later religious revival movement.[13] By Little Gidding, WWII is not just the present time but connected also to the English Civil War.[14]

Poems

Each poem has five sections. The later poems connect to the earlier sections, with Little Gidding synthesising the themes of the earlier poems within its sections.[15] Within Eliot's own poetry, the five sections connect to The Waste Land. This allowed Eliot to structure his larger poems, which he had difficulty with.[16]

According to C.K. Stead, the structure is based on:[17]

- The movement of time, in which brief moments of eternity are caught.

- Worldly experience, leading to dissatisfaction.

- Purgation in the world, divesting the soul of the love of created things.

- A lyric prayer for, or affirmation of the need of, intercession.

- The problem of attaining artistic wholeness, which becomes an analogue for and merges into the problem of achieving spiritual health.

These points can be applied to the structure of The Waste Land, though there is not necessarily a fulfilment of these but merely a longing or discussion of them.[18]

Burnt Norton

The poem begins with two epigraphs taken from the fragments of Heraclitus:

τοῦ λόγου δὲ ἐόντος ξυνοῦ ζώουσιν οἱ πολλοί

ὡς ἰδίαν ἔχοντες φρόνησιν

— I. p. 77. Fr. 2.

The first may be translated, "Though wisdom is common, the many live as if they have wisdom of their own";

---

ὁδὸς ἄνω κάτω μία καὶ ὡυτή

— I. p. 89 Fr. 60.

the second, "the way upward and the way downward is one and the same".[19]

The concept and origin of Burnt Norton is connected to Eliot's play Murder in the Cathedral.[20] The poem discusses the idea of time and the concept that only the present moment really matters because the past cannot be changed and the future is unknown.[21]

- In Part I, this meditative poem begins with the narrator trying to focus on the present moment while walking through a garden, focusing on images and sounds like the bird, the roses, clouds, and an empty pool.

- In Part II, the narrator's meditation leads him to reach "the still point" in which he doesn't try to get anywhere or to experience place and/or time, instead experiencing "a grace of sense."

- In Part III, the meditation experience becomes darker as night comes on, and

- by Part IV, it is night and "Time and the bell have buried the day."

- In Part V, the narrator reaches a contemplative end to his/her meditation, initially contemplating the arts ("Words" and "music") as they relate to time.

The narrator focuses particularly on the poet's art of manipulating "Words [which] strain,/Crack and sometimes break, under the burden [of time], under the tension, slip, slide, perish, decay with imprecision, [and] will not stay in place, /Will not stay still." By comparison, the narrator concludes that "Love is itself unmoving,/Only the cause and end of movement,/Timeless, and undesiring." For this reason, this spiritual experience of "Love" is the form of consciousness that most interests the narrator (presumably more than the creative act of writing poetry).

East Coker

Eliot started writing East Coker in 1939, and modelled the poem after Burnt Norton as a way to focus his thoughts. The poem served as a sort of opposite to the popular idea that The Waste Land served as an expression of disillusionment after World War I, though Eliot never accepted this interpretation.[4]

The poem focuses on life, death, and continuity between the two. Humans are seen as disorderly and science is viewed as unable to save mankind from its flaws:

Instead, science and reason lead mankind to warfare, and humanity needs to become humble in order to escape the cycle of destruction. To be saved, people must recognize Christ as their saviour as well as their need for redemption.[22]

The Dry Salvages

Eliot began writing The Dry Salvages at the end of 1940 during air-raids on London, and managed to finish the poem quickly. The poem included many personal images connecting to Eliot's childhood, and emphasised the image of water and sailing as a metaphor for humanity.[7] According to the poem, there is a connection to all of mankind within each man. If we just accept drifting upon the sea, then we will end up broken upon rocks. We are restrained by time, but the Annunciation [a pattern of nature - re slater] gave mankind hope that it will be able to escape. This hope is not part of the present. What we must do is understand the patterns found within the past [and within creation itself - re slater] in order to see that there is meaning to be found. This meaning allows one to experience eternity through moments of revelation.[23]

Little Gidding

Little Gidding was started after The Dry Salvages but was delayed because of Eliot's declining health and his dissatisfaction with early drafts of the poem. Eliot was unable to finish the poem until September 1942.[24] Like the three previous poems of the Four Quartets, the central theme is time and humanity's place within it. Each generation is seemingly united and the poem describes a unification within Western civilisation. When discussing World War II, the poem states that humanity is given a choice between the bombing of London or the Holy Spirit. God's love allows humankind to redeem itself and escape the living hell through purgation by fire; he drew the affirmative coda "All shall be well" from medieval mystic Julian of Norwich. The end of the poem describes how Eliot has attempted to help the world as a poet, and he parallels his work in language with working on the soul or working on society.[25]

Motifs

Eliot believed that even if a poem can mean different things to each reader, the "absolute" meaning of the poem needs to be discovered. The central meaning of the Four Quartets is to connect to European literary tradition in addition to its Christian themes.[26] It also seeks to unite with European literature to form a unity, especially in Eliot's creation of a "familiar compound ghost" who is supposed to connect to those like Stéphane Mallarmé, Edgar Allan Poe, Jonathan Swift, and William Butler Yeats.[26]

Time

Time is viewed as unredeemable and problematic, whereas eternity is beautiful and true. Living under time's influence is a problem. Within Burnt Norton section 3, people trapped in time are similar to those stuck in between life and death in Dante's Inferno Canto Three.[27]

When Eliot deals with the past in The Dry Salvages, he emphasises its importance to combat the influence of evolution as encouraging people to forget the past and care only about the present and the future. The present is capable of always reminding one of the past. These moments also rely on the idea of Krishna in the Bhagavad-Gita that death can come at any moment, and that the divine will is more important than considering the future.[28]

The Jesuit critic William F. Lynch, who believed that salvation happens within time and not outside of it, explained what Eliot was attempting to do in the Four Quartets when he wrote:

"it is hard to say no to the impression, if I may use a mixture of my own symbols and his, that the Christian imagination is finally limited to the element of fire, to the day of Pentecost, to the descent of the Holy Ghost upon the disciples. The revelation of eternity and time is of an intersection ... It seems not unseemly to suppose that Eliot's imagination (and is this not a theology?) is alive with points of intersection and of descent."[29]

He continued with a focus on how time operated within the poem:

"He seems to place our faith, our hope, and our love, not in the flux of time but in the points of time. I am sure his mind is interested in the line and time of Christ, whose Spirit is his total flux. But I am not so sure about his imagination. Is it, or is it not, an imagination which is saved from time's nausea or terror by points of intersection? ...

"There seems little doubt that Eliot is attracted above all by the image and the goal of immobility, and that in everything he seeks for approximations to this goal in the human order."

Lynch went on to point out that this understanding of time includes Asian influences.[30]

Throughout the poems, the end becomes the beginning and things constantly repeat.[31] This use of circular time is similar to the way Dante uses time in his Divine Comedy – Little Gidding ends with a rose garden image that is the same as the garden beginning Burnt Norton. The repetition of time affects memory and how one can travel through their own past to find permanency and the divine. Memory within the poem is similar to how St. Augustine discussed it, in that memory allows one to understand words and life. The only way to discover eternity is through memory, understanding the past, and transcending beyond time. Likewise, in the Augustinian view that Eliot shares, timeless words are connected to Christ as the Logos and how Christ calls upon mankind to join him in salvation.[32]

Music

The title Four Quartets connects to music, which appears also in Eliot's poems "Preludes", "Rhapsody on a Windy Night", and "A Song for Simeon" along with a 1942 lecture called "The Music of Poetry". Some critics have suggested that there were various classical works that Eliot focused on while writing the pieces.[16] In particular, within literary criticism there is an emphasis on Beethoven serving as a model. Some have disputed this claim.[8] However, Lyndall Gordon's biography of T.S. Eliot establishes that Eliot had Beethoven in mind while writing them.[33] The purpose of the quartet was to have multiple themes that intertwined with each other. Each section, as in the musical image, would be distinct even though they share the same performance. East Coker and The Dry Salvages are written in such a way as to make the poems continuous and create a "double-quartet".[34]

Eliot focused on sounds or "auditory imagination", as he called it. He doesn't always keep to this device, especially when he is more concerned with thematic development. He did fix many of these passages in revision.[35]

Dante and Christianity

Critics have compared Eliot to Yeats. Yeats believed that we live in a cyclical world, saying, "If it be true that God is a circle whose centre is everywhere, the saint goes to the centre, the poet and the artist to the ring where everything comes round again."[36] Eliot believed that such a [circular] system is stuck within time. Eliot was influenced by Yeats's reading of Dante. This appears in Eliot's Ash Wednesday by changing Yeats's "desire for absolution" away from a humanistic approach.[37] When Eliot wrote about personal topics, he tended to use Dante as a reference point. He also relied on Dante's imagery: the idea of the "refining fire" in the Four Quartets and in The Waste Land comes from Purgatorio, and the celestial rose and fire imagery of Paradiso makes its way into the series.[38]

If The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, Gerontion, The Waste Land, and The Hollow Men are Eliot's Inferno, Ash Wednesday seems to be Purgatorio, and the Four Quartets seems to be Paradiso[original research?].

The Four Quartets abandons time, as per Dante's conception of the Empyrean, and allows for opposites to co-exist together. As such, people are able to experience God directly as long as they know that they cannot fully understand or comprehend him.

Eliot tries to create a new system, according to Denis Donoghue, in which he is able to describe a Christianity that is not restricted by previous views that have fallen out of favour in modern society or contradicted by science. Eliot reasoned that he is not supposed to preach a theological system as a poet, but expose the reader to the ideas of religion. As Eliot stated in 1947: "if we learn to read poetry properly, the poet never persuades us to believe anything" and "What we learn from Dante, or the Bhagavad-Gita, or any other religious poetry is what it feels like to believe that religion."[39]

*According to Russell Kirk, "Nor is it possible to appreciate Eliot—whether or not one agrees with him—if one comes to Four Quartets with ideological blinders. Ideology, it must be remembered, is the attempt to supplant religious dogmas by political and scientistic dogmas. If one's first premise is that religion must be a snare and a delusion, for instance, then it follows that Eliot becomes an enemy to be assaulted, rather than a pilgrim whose journal one may admire-even if one does not believe in the goal of that quest."[40]

Krishna

Eliot's poetry is filled with religious images beyond those common to Christianity: the Four Quartets brings in Hindu stories with a particular emphasis on the Bhagavad-Gita of the Mahabharata.[41] Eliot went so far as to mark where he alludes to Hindu stories in his editions of the Mahabharata by including a page added which compared battle scenes with The Dry Salvages.[42]

Critical responses

Miguel Angel Montezanti El nudo coronado. Estudio de Cuatro cuartetos; 1994 Reviews were favourable for each poem. The completed set received divided reviews in the United States while it was received overall favourably by the British. The American critics liked the poetry but many did not appreciate the religious content of the work or that Eliot abandoned philosophical aspects of his earlier poetry. The British response was connected to Eliot's nationalistic spirit, and the work was received as a series of poems intended to help the nation during difficult times.[43] Santwana Haldar went so far as to assert that the "Four Quartets has been universally appreciated as the crown of Eliot's achievement in religious poetry, one that appeals to all including those who do not share Orthodox Christian creed."[44]

George Orwell believed just the opposite. He argued: "It is clear that something has departed, some kind of current has been switched off, the later verse does not contain the earlier, even if it is claimed as an improvement upon it [...] He does not really feel his faith, but merely assents to it for complex reasons. It does not in itself give him any fresh literary impulse."[45] Years later, Russell Kirk wrote, "I cannot agree with Orwell that Eliot gave no more than a melancholy assent to doctrines now quite unbelievable. Over the past quarter of a century, most serious critics—whether or not they find Christian faith impossible—have found in the Quartets the greatest twentieth-century achievements in the poetry of philosophy and religion."[46] Like Orwell, Stead also noticed a difference between the Four Quartets and Eliot's earlier poetry, but he disagreed with Orwell's conclusion: "Four Quartets is an attempt to bring into a more exact balance the will and the creative imagination; it attempts to harness the creative imagination which in all Eliot's earlier poetry ran its own course, edited but not consciously directed. The achievement is of a high order, but the best qualities of Four Quartets are inevitably different from those of The Waste Land.[47]

Early American reviewers were divided on discussing the theological aspects of the Four Quartets. F. R. Leavis, in Scrutiny (Summer 1942), analysed the first three poems and discussed how the verse "makes its explorations into the concrete realities of experience below the conceptual currency" instead of their Christian themes.[48] Muriel Bradbrook, in Theology (March 1943), did the opposite of F. R. Leavis and emphasised how Eliot captured Christian experience in general and how it relates to literature. D. W. Harding, in the Spring 1943 issue of Scrutiny, discussed the Pentecostal image but would not discuss how it would relate to Eliot's Christianity. Although he appreciated Eliot's work, Paul Goodman believed that the despair found within the poem meant that Eliot could not be a Christian poet. John Fletcher felt that Eliot's understanding of salvation could not help the real world whereas Louis Untermeyer believed that not everyone would understand the poems.[49]

Many critics have emphasised the importance of the religious themes in the poem. Vincent Buckley stated that the Four Quartets "presuppose certain values as necessary for their very structure as poems yet devote that structure to questioning their meaning and relevance. The whole work is, in fact, the most authentic example I know in modern poetry of a satisfying religio-poetic meditation. We sense throughout it is not merely a building-up of an intricate poetic form on the foundation of experiences already over and done with, but a constant energy, an ever-present activity, of thinking and feeling."[50] In his analysis of approaches regarding apocalypse and religious in British poetry, M. H. Abrams claimed, "Even after a quarter-century, T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets has not lost its status as a strikingly 'modern' poem; its evolving meditations, however, merely play complex variations upon the design and motifs of Romantic representation of the poets educational progress."[51]

Late 20th century and early 21st century critics continued the religious emphasis. Craig Raine pointed out: "Undeniably, Four Quartets has its faults—for instance, the elementary tautology of 'anxious worried women' in section I of The Dry Salvages. But the passages documenting in undeniable detail 'the moment in and out of time' are the most successful attempts at the mystical in poetry since Wordsworth's spots of time in The Prelude—themselves a refiguration of the mystical."[52] Michael Bell argued for the universality within the poems' religious dimension and claimed that the poems "were genuinely of their time in that, while speaking of religious faith, they did not assume it in the reader."[53] John Cooper, in regard to the poem's place within the historical context of World War II, described the aspects of the series appeal: "Four Quartets spoke about the spirit in the midst of this new crisis and, not surprisingly, there were many readers who would not only allow the poem to carry them with it, but who also hungered for it."[54]

In a more secular appreciation, one of Eliot's biographers, the critic Peter Ackroyd, has stated that "the most striking characteristic of The Four Quartets is the way in which these sequences are very carefully structured. They echo and re-echo each other, and one sequence in each poem, as it were, echoes its companion sequence in the next poem. . . The Four Quartets are poems about a nation and about a culture which is very severely under threat, and in a sense, you could describe The Four Quartets as a poem of memory, but not the memory of one individual but the memory of a whole civilization."[55]

In a 2019 interview, conservative philosopher Roger Scruton stated that "...(T. S. Eliot influenced) my vision of culture. And that’s from school days: I came across Four Quartets aged 16 and that made sense of everything for the first time."[56] American author Ross Douthat writes of the poem: "This is a poetic counterpart to Chesterton's prose. Eliot's verse makes no argument, but distills the religious impulse and his own Christian hope to eloquent perfection."[57]

See also

References

- Endnotes

- ^ Orwell, George, 1903-1950. (2008). All art is propaganda : critical essays. Packer, George, 1960- (1st ed.). Orlando: Harcourt. ISBN 9780151013555. OCLC 214322739.

- ^ Ackroyd 1984 p. 228

- ^ Grant 1997 p. 37

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ackroyd 1984 pp. 254–255

- ^ Pinion 1986 p. 48

- ^ Ackroyd 1984 pp. 262–266

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ackroyd 1984 p. 262

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pinion 1986 p. 219.

- ^ Gardner 1978 qtd. p. 26

- ^ Kirk 2008 p. 239

- ^ Kirk 2008 p. 266

- ^ Moody 2006 p. 143

- ^ Bergonzi 1972 pp. 150–154

- ^ Bergonzi 1972 pp. 172

- ^ Ackroyd 1984 p. 270

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bergonzi 1972 p. 164

- ^ Stead 1969 p. 171

- ^ Bergonzi 1972 p. 165

- ^ Diels, Hermann; Burnet, John Translator. "Heraclitus 139 Fragments" (PDF) (in Greek and English).

- ^ Ackroyd 1984 pp. 228–230

- ^ Kirk 2008 pp. 246–247

- ^ Kirk 2008 pp. 250–252

- ^ Kirk 2008 pp. 254–255

- ^ Ackroyd 1984 pp. 263–266

- ^ Kirk 2008 pp. 260–263

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ackroyd 1984 p. 271

- ^ Bergonzi 1972 pp. 166–7

- ^ Pinion 1986 p. 227

- ^ Bergonzi 1972 qtd. p. 168

- ^ Bergonzi qtd. 1972 pp. 168–169

- ^ Gordon 2000 p. 341

- ^ Manganiello 1989 pp. 115–119

- ^ Gordon, Lyndall (1 November 2000). T.S Eliot: An Imperfect Life. W.W. Norton and company. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-393-32093-0.

- ^ Moody 2006 pp. 143–144

- ^ Ackroyd 1984 pp. 265–266

- ^ Manganiello 1989 p. 150

- ^ Manganiello 1989 pp. 150–152

- ^ Bergonzi 1972 pp. 171–173

- ^ Kirk 2008 qtd. pp. 241–243

- ^ Kirk 2008 p. 244

- ^ Pinion 1986 pp. 226–227

- ^ Gordon 2000 p. 85

- ^ Ackroyd 1984 pp. 262–269

- ^ Haldar 2005 p. 94

- ^ Kirk 2008 qtd p. 240

- ^ Kirk 2008 p. 240

- ^ Stead 1969 p. 176

- ^ Grant 1997 qtd. p. 44

- ^ Grant 1997 pp. 44–46

- ^ Kirk 2008 qtd. pp. 240–241

- ^ Abrams 1973 p. 319

- ^ Raine 2006 p. 113

- ^ Bell 1997 p. 124

- ^ Cooper 2008 p. 23

- ^ T.S. Eliot. Voices and Visions Series. New York Center of Visual History: PBS, 1988.[1]

- ^ "The Roger Scruton interview: the full transcript". New Statesman. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Douthat, Ross (15 April 2018). "Ross Douthat's 6 favorite books on religion". The Week. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- Bibliography

- Abrams, Meyer Howard. Natural Supernaturalism: Traditional Revolution in Romantic Literature. W.W Norton and Company, 1973. ISBN 0-393-00609-3

- Ackroyd, Peter. T. S. Eliot: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984. ISBN 0-671-53043-7

- Bell, Michael. Literature, Modernism, and Myth Belief and Responsibility in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-585-00052-2

- Bergonzi, Bernard. T. S. Eliot. New York: Macmillan Company, 1972. OCLC 262820

- Cooper, John. T. S. Eliot and the ideology of Four Quartets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-521-06091-2

- Gallup, Donald. T. S. Eliot: A Bibliography (A Revised and Extended Edition). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1969. OCLC 98808

- Gardner, Helen. The Composition of "Four Quartets". New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-19-519989-8

- Gordon, Lyndall. T. S. Eliot: An Imperfect Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04728-8

- Grant, Michael, T. S. Eliot: The Critical Heritage. New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0-7100-9224-5

- Haldar, Santwana. T. S. Eliot : A Twenty-first Century View. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 2005. ISBN 81-269-0414-3

- Howard, Thomas. Dove Descending: A Journey Into T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets. Ignatius Press, 2006. ISBN 1-58617-040-6

- Kirk, Russell. Eliot and His Age: T.S. Eliot's Moral Imagination in the Twentieth Century. Wilmington: ISI Books, 2008. OCLC 80106144

- Manganiello, Dominic. T. S. Eliot and Dante. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989. ISBN 0-312-02104-6

- Moody, A. David. "Four Quartets: Music, Word, Meaning and Value" in The Cambridge Companion to T. S. Eliot, ed. A. David Moody, 142–157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-42080-6

- Newman, Barbara. "Eliot's Affirmative Way: Julian of Norwich, Charles Williams, and Little Gidding." Modern Philology 108 (2011): 427–61. doi:10.1086/658355 JSTOR 10.1086/658355

- Oser, Lee. "Coming to Terms with Four Quartets." Blackwell Companion to T. S. Eliot. Ed. David Chinitz. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 216-227. doi:10.1002/9781444315738

- Pinion, F. B. A T. S. Eliot Companion. London: MacMillan, 1986. OCLC 246986356

- Raine, Craig. T. S. Eliot. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Stead, Christian. The New Poetic: Yeats to Eliot. Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, 1969. OCLC 312358328