For those who like to figure out riddles go no further in your reading

than the poem shown here. The poem has been written in such a way

so that there may be many possible conjectures. But once a solution

has been read the creativity to the reader's conjecture may be

dramatically reduced in imagination and type form. So, read

the poem, then re-read it, and come to your own thots first!

- Enjoy!

so that there may be many possible conjectures. But once a solution

has been read the creativity to the reader's conjecture may be

dramatically reduced in imagination and type form. So, read

the poem, then re-read it, and come to your own thots first!

- Enjoy!

PS... And when you've read as much of this post and it's historic framing

as possible, this next post I created five and half years later will offer a few

suggestions to your own posits and conjectures here today. Have fun!

施氏食狮史

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

A 20th century romanized phonetic poem "Shi Shi" by Chinese-American linguist Yuen Ren Chao expresses the homophonic traditions of old Classical Chinese illustrating the language's tonal intricacies when expressed in Pinyin (modern Mandarin). When reading the riddle every syllable has the sound “shi” with only the tonal values differing.

THE LION EATING POET IN THE STONE DEN

In a stone den was a poet called Shi Shi, who was a lion addict, and had resolved to eat ten lions.

He often went to the market to look for lions.

At ten o’clock, ten lions had just arrived at the market.

At that time, Shi had just arrived at the market.

He saw those ten lions, and using his trusty arrows, caused the ten lions to die.

He brought the corpses of the ten lions to the stone den.

The stone den was damp. He asked his servants to wipe it.

After the stone den was wiped, he tried to eat those ten lions.

When he ate, he realized that these ten lions were in fact ten stone lion corpses.

Try to explain this matter.

* * * * * *

You may wish to stop here, at this point, and attempt to give your own imaginings first before reading any further in this present article. My own favorite imagining is the one given here by Red Slider in his very clever solution worthy of the art form itself! But then again, I have provided my own offerings here in this follow up post. But before going there, read through the remainder of today's post so to appreciate the cultural background of Shi-Shi.

Enjoy! - re slater

* * * * * *

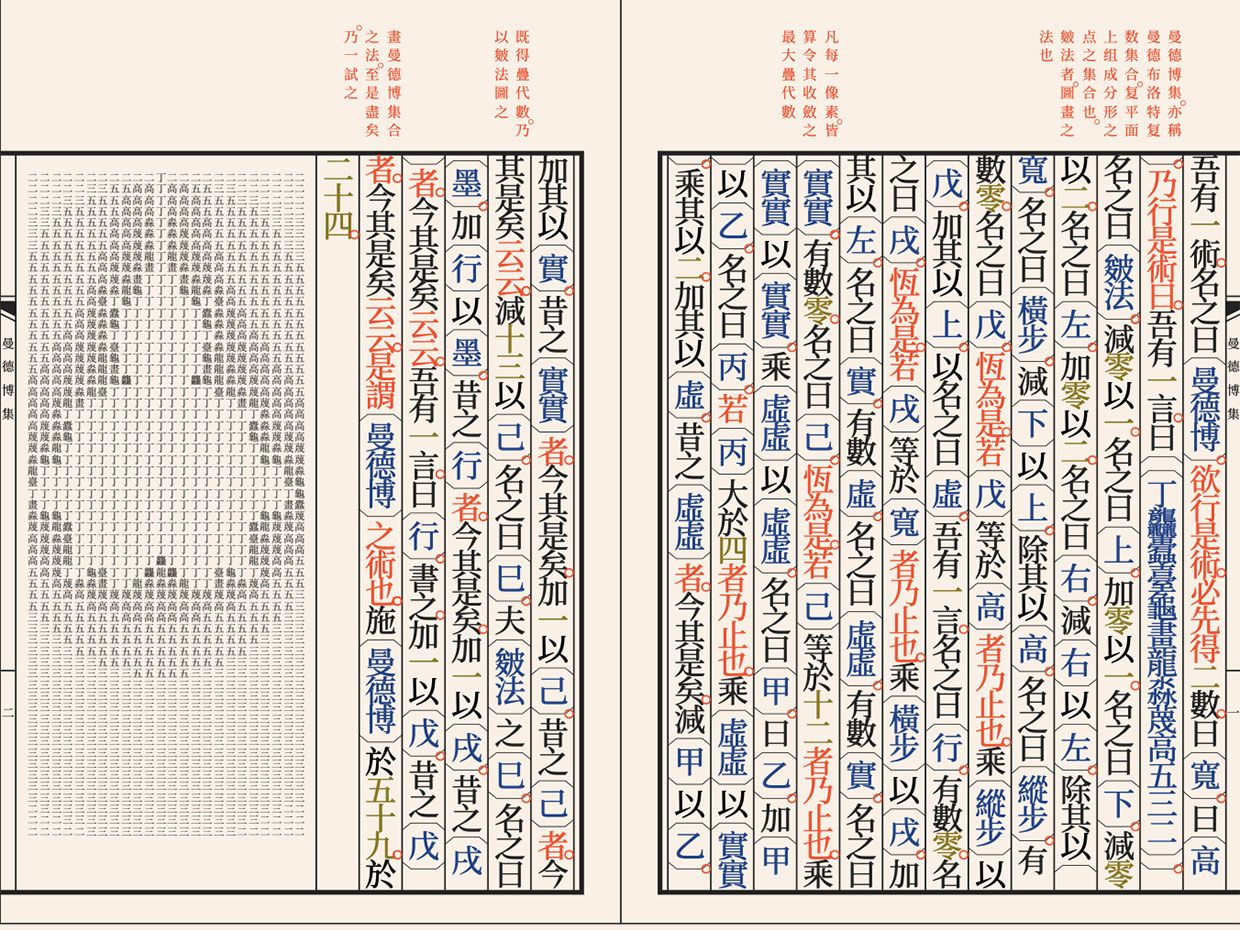

The Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den (Chinese: 施氏食獅史; pinyin: Shī-shì shí shī shǐ) is a short narrative poem written in Classical Chinese that is composed of 92 characters in which every word is pronounced shi ([ʂɻ̩]) when read in present-day Standard Mandarin, with only the tones differing.[1]

The poem was written in the 1930s by the Chinese linguist Yuen Ren Chao as a linguistic demonstration. The poem is coherent and grammatical in Classical Chinese, but the loss of older sound combinations in Chinese over the centuries has greatly increased the number of Chinese homophones, making Classical Chinese difficult to understand in oral speech. In Mandarin, the poem is incomprehensible when read aloud, since only four syllables cover the entire 92 words of the poem. The poem is less incomprehensible—but still not very intelligible—when read in other varieties of Chinese such as Cantonese, in which it has 22 different syllables, or Hokkien Chinese, in which it has 15 different syllables.

The poem is an example of a one-syllable article, a form of constrained writing possible in tonal languages such as Mandarin Chinese, where tonal contours expand the range of meaning for a single syllable.

Explanation

Chinese is a tonal language in which subtle changes in pronunciation could change the meaning.[2] In Romanized script, the poem is an example of the antanaclasis in Chinese.[2] The poem shows the flexibility of the Chinese language in many ways, including wording, syntax, punctuation and sentence structures, which gives rise to various explanations.[3]

The poem could be misinterpreted as objection to the Romanization of Chinese. However, the 20th-century author Yuen Ren Chao was a major supporter for Romanization. He used this poem as an example to object to the use of Classical Chinese that is hardly used in daily life.[4][5]

The poem is easy to understand when read in its written form in Chinese characters, due to each character being associated with a different core meaning, or in its spoken form in those Sinitic languages other than Mandarin. However, when it is in its transcribed Romanized form or in its spoken Mandarin form, it becomes confusing.[4]

Many words in the passage had distinct sounds in Middle Chinese. All of the variants of spoken Chinese have, over time, merged and split different sounds. For example, when the same passage is read in Cantonese (even modern Cantonese) there are seven distinct syllables—ci, sai, sap, sat, sek, si, sik—in six distinct tone contours, producing 22 distinct character pronunciations. In Southern Min, there are six distinct syllables—se, si, su, sek, sip, sit—in seven distinct tone contours, producing fifteen character pronunciations. Therefore, the passage is barely comprehensible when read aloud in modern Mandarin without context, but easier to understand when read in other Sinitic languages, such as Cantonese.

References

Behr, Wolfgang (2015). "Discussion 6: G. Sampson, "A Chinese Phonological Enigma": Four Comments". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 43 (2): 719–732. ISSN 0091-3723. JSTOR 24774984.

Forsyth, Mark. (2011). The Etymologicon : a Circular Stroll through the Hidden Connections of the English Language. Cambridge: Icon Books. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781848313224. OCLC 782875800.

Hengxing, He (2018-02-01). "The Discourse Flexibility of Zhao Yuanren [Yuen Ren Chao]'s Homophonic Text". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 46 (1): 149–176. doi:10.1353/jcl.2018.0005. ISSN 2411-3484.

彭, 泽润 (2009). "赵元任的"狮子"不能乱"吃"——文言文可以看不能听的原理" [Zhao Yuanren's "lion" cannot be "eaten": the reasons why Classical Chinese can be read instead of being listened to]. 现代语文:下旬.语言研究 (12): 160.

张, 巨龄 (11 January 2015). "赵元任为什么写"施氏食狮史"" [Why Zhao Yuanren wrote Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den]. 光明日报. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

* * * * * *

The Story of Mr Shi Eating Lions, recited in Mandarin Chinese

Lion-Eating Poet - Chinese Tongue Twister

Counting Tongue Twister in Mandarin Chinese: sì shì sì

Learn ALL 249 Chinese HSK words with “shi”

(with example sentences)

Opening Illustrations to Video:

Learn ALL 249 Chinese HSK words with “shi”

(with example sentences)

* * * * * *

HOW TO READ A CHINESE POEM

WITH ONLY ONE SOUND

by Aaron Posehn

Learning Chinese can be a struggle, especially if you’ve just started out on the path to fluency. The tones, the characters, and the difficult sounds that you might not be familiar with can be a challenge to grasp.

However, once you’ve spent some time learning the basics, next comes reading articles, writing short in-class essays, and even perhaps the ability to understand TV shows and movies.

But once you’re fairly comfortable in these areas, you might take your Chinese even further and dive into the ever obscure Classic Chinese.

Truthfully, it’s not really that bad, but it often differs significantly from the Mandarin that is used in everyday life.

If you’re not familiar with Classical Chinese, here’s a quick example of a famous line attributed to Confucius.

Classical Chinese Simplified: 有朋自远方来,不亦乐乎?

Classical Chinese Traditional: 有朋自遠方來,不亦樂乎?

Pinyin: Yǒu péng zì yuǎnfāng lái, bù yì lè hū?

Modern Chinese Simplified: 有朋友从远方来,不也快乐吗?

Modern Chinese Traditional: 有朋友從遠方來,不也快樂嗎?

Pinyin: Yǒu péngyǒu cóng yuǎnfāng lái, bù yě kuàilè ma?

English: Is it not a delight to have friends come from afar?

Some of the most noticeable differences are in the following words:

朋 (péng) vs. 朋友 (péng yǒu) – friend

自 (zì) vs. 从 (cóng) – from

乐 (lè) vs. 快乐 (kuài lè) – happiness, a delight

乎 (hū) vs. 吗 (ma) – question particle.

You may notice that Classical Chinese often uses only one character where modern Chinese might use two or more. This is okay though, because Classical Chinese is primarily a written language, so if you know what a string of single characters mean, that’s often good enough to understand the sentence (unless the characters have more than one meaning, which they might; the characters might have also meant something different in Classical Chinese than they do in modern Chinese, so there’s also that to watch out for).

One very interesting and famous Classical Chinese poem that I’ve marveled at for some time is that of the “Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den,” or 施氏食狮史 (shī shì shí shī shǐ).

You may have already realized that each character in the title is pronounced “shi,” and indeed, every character in the whole poem is also pronounced this way! This is possible because, although a character may have the same sound as another character, it can have a different tone and can be written with a different character, and so this kind of craziness is possible in Chinese. Remember how I said that you only need to know the meaning of a single character in a string of single characters to understand (more or less) Classical Chinese? This is the case here. If you know the meaning of each character in the poem, even though it’s more of a tongue twister than a verse, you’ll be able to understand it. Here’s the poem below:

Simplified Chinese:

《施氏食狮史》

石室诗士施氏,嗜狮,誓食十狮。

氏时时适市视狮。

十时,适十狮适市。

是时,适施氏适市。

氏视是十狮,恃矢势,使是十狮逝世。

氏拾是十狮尸,适石室。

石室湿,氏使侍拭石室。

石室拭,氏始试食是十狮。

食时,始识是十狮尸,实十石狮尸。

试释是事。

Traditional Chinese:

《施氏食獅史》

石室詩士施氏,嗜獅,誓食十獅。

氏時時適市視獅。

十時,適十獅適市。

是時,適施氏適市。

氏視是十獅,恃矢勢,使是十獅逝世。

氏拾是十獅屍,適石室。

石室濕,氏使侍拭石室。

石室拭,氏始試食是十獅。

食時,始識是十獅屍,實十石獅屍。

試釋是事。

Pinyin:

« Shī Shì shí shī shǐ »

Shíshì shīshì Shī Shì, shì shī, shì shí shí shī.

Shì shíshí shì shì shì shī.

Shí shí, shì shí shī shì shì.

Shì shí, shì Shī Shì shì shì.

Shì shì shì shí shī, shì shǐ shì, shǐ shì shí shī shìshì.

Shì shí shì shí shī shī, shì shíshì.

Shíshì shī, Shì shǐ shì shì shíshì.

Shíshì shì, Shì shǐ shì shí shì shí shī.

Shí shí, shǐ shí shì shí shī shī, shí shí shí shī shī.

Shì shì shì shì.

English:

« Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den »

In a stone den was a poet called Shi Shi, who was a lion addict,

and had resolved to eat ten lions.

He often went to the market to look for lions.

At ten o’clock, ten lions had just arrived at the market.

At that time, Shi had just arrived at the market.

He saw those ten lions, and using his trusty arrows, caused the ten lions to die.

He brought the corpses of the ten lions to the stone den.

The stone den was damp. He asked his servants to wipe it.

After the stone den was wiped, he tried to eat those ten lions.

When he ate, he realized that these ten lions were in fact ten stone lion corpses.

Try to explain this matter.

If you got all the way through the poem without crying, good for you! You’ve probably got some awesome Chinese skills! However, if you want to challenge yourself, you can go on over to Wikipedia’s page about this poem to see how it would be pronounced in other Chinese languages, such as Cantonese, Hakka, Taiwanese, or even the original Classical Chinese pronunciation. They also show you how this poem would be read in the vernacular Mandarin used today; you can read that here. If you’re not totally scared off by Classical Chinese yet, that’s great. I personally think it’s a very interesting written language, full of such interesting gems as the poem just shown above. If you want to dive deeper into it, you can start out by going here, here, or here. So the next time your Chinese friends come from afar, you can delight them with your knowledge of this little poem. They’ll probably agree that it was worth coming just to hear you try and say it.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

|

| The Structure of Chinese Script |

|

| Jan 2020 - World's First Classical Chinese Programming Language |

The fuller Wikipedia article linked here to

Classical Chinese would useful to understanding

its Romanization known as Pinyin in Mandarin

"Classical Chinese, also known as Literary Chinese,[a] is the language of the classic literature from the end of the Spring and Autumn period through to the end of the Han dynasty, a written form of Old Chinese. Classical Chinese is a traditional style of written Chinese that evolved from the classical language, making it different from any modern spoken form of Chinese. Literary Chinese was used for almost all formal writing in China until the early 20th century, and also, during various periods, in Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Among Chinese speakers, Literary Chinese has been largely replaced by written vernacular Chinese, a style of writing that is similar to modern spoken Mandarin Chinese, while speakers of non-Chinese languages have largely abandoned Literary Chinese in favor of local vernaculars."

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Mandarin (/ˈmændərɪn/ ( listen); simplified Chinese: 官话; traditional Chinese: 官話; pinyin: Guānhuà; literally: 'speech of officials') is a group of Sinitic (Chinese) languages spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of Standard Chinese. Because Mandarin originated in North China and most Mandarin languages and dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as Northern Chinese (北方话, běifānghuà, 'northern speech'). Many varieties of Mandarin, such those of the Southwest (including Sichuanese) and the Lower Yangtze (including the old capital Nanjing), are not mutually intelligible or are only partially intelligible with the standard language. Nevertheless, Mandarin is often placed first in lists of languages by number of native speakers (with nearly a billion).

listen); simplified Chinese: 官话; traditional Chinese: 官話; pinyin: Guānhuà; literally: 'speech of officials') is a group of Sinitic (Chinese) languages spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of Standard Chinese. Because Mandarin originated in North China and most Mandarin languages and dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as Northern Chinese (北方话, běifānghuà, 'northern speech'). Many varieties of Mandarin, such those of the Southwest (including Sichuanese) and the Lower Yangtze (including the old capital Nanjing), are not mutually intelligible or are only partially intelligible with the standard language. Nevertheless, Mandarin is often placed first in lists of languages by number of native speakers (with nearly a billion).

listen); simplified Chinese: 官话; traditional Chinese: 官話; pinyin: Guānhuà; literally: 'speech of officials') is a group of Sinitic (Chinese) languages spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of Standard Chinese. Because Mandarin originated in North China and most Mandarin languages and dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as Northern Chinese (北方话, běifānghuà, 'northern speech'). Many varieties of Mandarin, such those of the Southwest (including Sichuanese) and the Lower Yangtze (including the old capital Nanjing), are not mutually intelligible or are only partially intelligible with the standard language. Nevertheless, Mandarin is often placed first in lists of languages by number of native speakers (with nearly a billion).

listen); simplified Chinese: 官话; traditional Chinese: 官話; pinyin: Guānhuà; literally: 'speech of officials') is a group of Sinitic (Chinese) languages spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of Standard Chinese. Because Mandarin originated in North China and most Mandarin languages and dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as Northern Chinese (北方话, běifānghuà, 'northern speech'). Many varieties of Mandarin, such those of the Southwest (including Sichuanese) and the Lower Yangtze (including the old capital Nanjing), are not mutually intelligible or are only partially intelligible with the standard language. Nevertheless, Mandarin is often placed first in lists of languages by number of native speakers (with nearly a billion).

Mandarin is by far the largest of the seven or ten Chinese dialect groups, spoken by 70 percent of all Chinese speakers over a large geographical area, stretching from Yunnan in the southwest to Xinjiang in the northwest and Heilongjiang in the northeast. This is generally attributed to the greater ease of travel and communication in the North China Plain compared to the more mountainous south, combined with the relatively recent spread of Mandarin to frontier areas.

Most Mandarin varieties have four tones. The final stops of Middle Chinese have disappeared in most of these varieties, but some have merged them as a final glottal stop. Many Mandarin varieties, including the Beijing dialect, retain retroflex initial consonants, which have been lost in southern varieties of Chinese.

The capital has been within the Mandarin area for most of the last millennium, making these dialects very influential. Some form of Mandarin has served as a national lingua franca since the 14th century. In the early 20th century, a standard form based on the Beijing dialect, with elements from other Mandarin dialects, was adopted as the national language. Standard Chinese is the official language of the People's Republic of China[4] and Taiwan[5] and one of the four official languages of Singapore. It is used as one of the working languages of the United Nations.[6] It is also one of the most frequently used varieties of Chinese among Chinese diaspora communities internationally and the most commonly taught Chinese variety

* * * * * *

This article is about the variety of Chinese widely spoken in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau. For related languages and dialects, see Yue Chinese. For other uses, see Cantonese (disambiguation).

Cantonese is a variety of Chinese originating from the city of Guangzhou (also known as Canton) and its surrounding area in Southeastern China. It is the traditional prestige variety of the Yue Chinese dialect group, which has about 68 million native speakers.[3] While the term Cantonese specifically refers to the prestige variety, it is often used to refer to the entire Yue subgroup of Chinese, including related but largely mutually unintelligible languages and dialects such as Taishanese.

Cantonese is viewed as a vital and inseparable part of the cultural identity for its native speakers across large swaths of Southeastern China, Hong Kong and Macau, as well as in overseas communities. In mainland China, it is the lingua franca of the province of Guangdong (being the majority language of the Pearl River Delta) and neighbouring areas such as Guangxi. It is the dominant and official language of Hong Kong and Macau. Cantonese is also widely spoken amongst Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia (most notably in Vietnam and Malaysia, as well as in Cambodia and Singapore to a lesser extent) and throughout the Western world.

Although Cantonese shares much vocabulary with Mandarin, the two varieties are mutually unintelligible because of differences in pronunciation, grammar and lexicon. Sentence structure, in particular the placement of verbs, sometimes differs between the two varieties. A notable difference between Cantonese and Mandarin is how the spoken word is written; both can be recorded verbatim, but very few Cantonese speakers are knowledgeable in the full Cantonese written vocabulary, so a non-verbatim formalized written form is adopted, which is more akin to the Mandarin written form.[4][5] This results in the situation in which a Cantonese and a Mandarin text may look similar but are pronounced differently.

DIALECTS IN CHINA

* * * * * * *

WHAT IS PINYIN?

by Sara Lynn Hua

October 19, 2015

Pinyin is the Romanization of the Chinese characters based on their pronunciation. In Mandarin Chinese, the phrase “Pin Yin” literally translates into “spell sound.” In other words, spelling out Chinese phrases with letters from the English alphabet.

For example:

Characters: 学习中文

Pinyin: xué xí zhōng wén

Historically, Pinyin started as a means of explaining Chinese to Western learners. It wasn’t until the Qing Dynasty that Chinese people really started considering adopting a form of spelling in their writing system. According to some scholars, the beginnings of Pinyin were derived after the Chinese observed the Romaji system and Western learning in Japan.

The Chinese government did not officially recognize this language form until the 1950s, when it became a project headed by Zhou Youguang and a team of linguists. It was then introduced in elementary school in order to improve literacy rates as well as help standardize the pronunciation of Chinese characters.

In the digital age, Pinyin has become exceedingly useful, as it is the most popular and common way to type out Chinese characters on a typical keyboard. Touch-screen devices allow you to draw out the character, which is often unreliable (depending on how bad your handwriting is) and more time consuming.

To those without any knowledge of the Chinese language, Pinyin can look confusing. There are many combinations of letters that do not exist in English. For example, words like “xi,” “qie,” and “cui.” In addition to that, many letters are pronounced differently than they are English. “C” in Chinese is pronounced like the “ts” sound in “grits” as opposed to the “k” sound it makes in English.

When learning Pinyin, you should discard any rules you think you know about languages that use the English alphabet. Xi and Si look like they rhyme, right? Wrong! Xi is pronounced a little like “see / shee,” whereas “Si” is pronounced closer to “sih / suh.”

To make things even more complicated, there are also four tones in Mandarin that help clarify meanings in words. When written, accent marks or numbers are often used to denote the tone. They are listed below:

ma1 or mā (high level tone)Imagine the tone of your voice if you were asked to sing a pitch, “aaaaah.”

ma2 or má (rising tone)Imagine the tone of your voice when you ask a question, such as “Huh?”

ma3 or mǎ (falling rising tone)Imagine the tone of your voice when you say the word “meow.”

ma4 or mà (falling tone)Imagine the tone of your voice when you say an order, such as “Stop!”

Improper usage of the tone can result in completely different words. For example, shuǐ jiǎo (dumpling) and shuì jiào (sleep) have the same spelling, but different tones. It can make for an awkward moment if you accidently ask your waitress to sleep with you instead of asking for some dumplings.

|

| Amazon Link |

"This book is an introduction in the very best sense of the word. It provides the beginner with an accurate, sophisticated, yet accessible account, and offers new insights and challenging perspectives to those who have more specialized knowledge. Focusing on the period in Chinese philosophy that is surely most easily approachable and perhaps is most important, it ranges over of rich set of competing options. It also, with admirable self-consciousness, presents a number of daring attempts to relate those options to philosophical figures and movements from the West. I recommend it very highly."

- Lee H. Yearley, Walter Y. Evans-Wentz Professor, Religious Studies, Stanford University

Review

This lucid introduction to early Chinese thought offers historical, textual and conceptual analyses of the schools of Classical Chinese philosophy, illuminating their basic themes, theories, and arguments and providing readers with an intellectual bridge between Chinese and Western thought. Introductory texts such as this are especially needed today, as the study of philosophy faces the challenges of globalization and the urgent need for dialogue among different philosophical traditions. An ideal text for introductory courses, this book will also inspire graduate students, scholars and experts in philosophy in general, and Chinese Philosophy in particular, with its theoretical insights and comparative methodology.

- Vincent Shen, Lee Chair in Chinese Thought and Culture, Departments of Philosophy and East Asian Studies, University of Toronto

A substantial and highly accessible introduction to the indigenous philosophies of China. Van Norden shares his clear distillations of classical Chinese philosophies using conceptual frameworks many will find familiar. This reader-friendly book sets the historical and cultural contexts for the philosophies discussed, and includes appendices, study questions, and imaginative scenarios, which aid us in appreciating some of the most important philosophy ever developed.

- Ann Pirruccello, Professor of Philosophy, University of San Diego

About the Author

Bryan W. Van Norden is Professor in the Philosophy Department, and in the department of Chinese and Japanese, at Vassar College.

* * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

This new edition offers expanded selections from the works of Kongzi (Confucius), Mengzi (Mencius), Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu), and Xunzi (Hsun Tzu); two new works, the dialogues Robber Zhi and White Horse; a concise general introduction; brief introductions to, and selective bibliographies for, each work; and four appendices that shed light on important figures, periods, texts, and terms in Chinese thought.

this is all very good and well, much detail on linguistics and such. But never actually does what its title suggests it will do, "What Does It Mean?? Interpreting the Riddle of the "Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den"

ReplyDeleteThere is not a word on this page that Interprets the story of 'Shi' or answers the question that Yuen Ren Chao presented to us in the last line of the poem, "Try to explain what this means." The reason is fairly simple. It is because, though everyone calls "She and the Ten Stone Lions" a 'poem', nobody seems to read it as one. If read as a poem, and interpreted using the common devices of interpreting poetry, the riddle is easily answered.

For those curious about the answer to the riddle of 'Shi', you will find it at http://poems4change.org/essays/shi-riddle-solution.pdf

yes. I had this posted originally but the author asked me to take it down. I am glad you found it!

ReplyDelete