|

| The Lorax, 1971 (Credit: Dr Seuss/Courtesy of Random House Children’s Books) |

by Fiona Macdonald

2nd March 2019

On the 115th anniversary of Dr Seuss’ birth, Fiona Macdonald looks at how creating wartime propaganda honed his unique vision.

“Step with care and great tact

and remember that Life’s

a Great Balancing Act.

Just never forget to be dexterous and deft.

And never mix up your right foot with your left.”

- Oh, The Places You’ll Go! (1960)

There’s a healthy dollop of wisdom percolating through the slapstick silliness and anarchic absurdity of Dr Seuss. More perhaps than any other children’s author, the musings of US writer and illustrator Theodor Seuss Geisel – who adopted the pen name Dr Seuss while at college – amount to a kind of philosophy. It’s one that has entered popular consciousness, contributing to pop song lyrics and even being cited by a Supreme Court judge. Yet there’s also a political edge to Dr Seuss that is often overlooked.

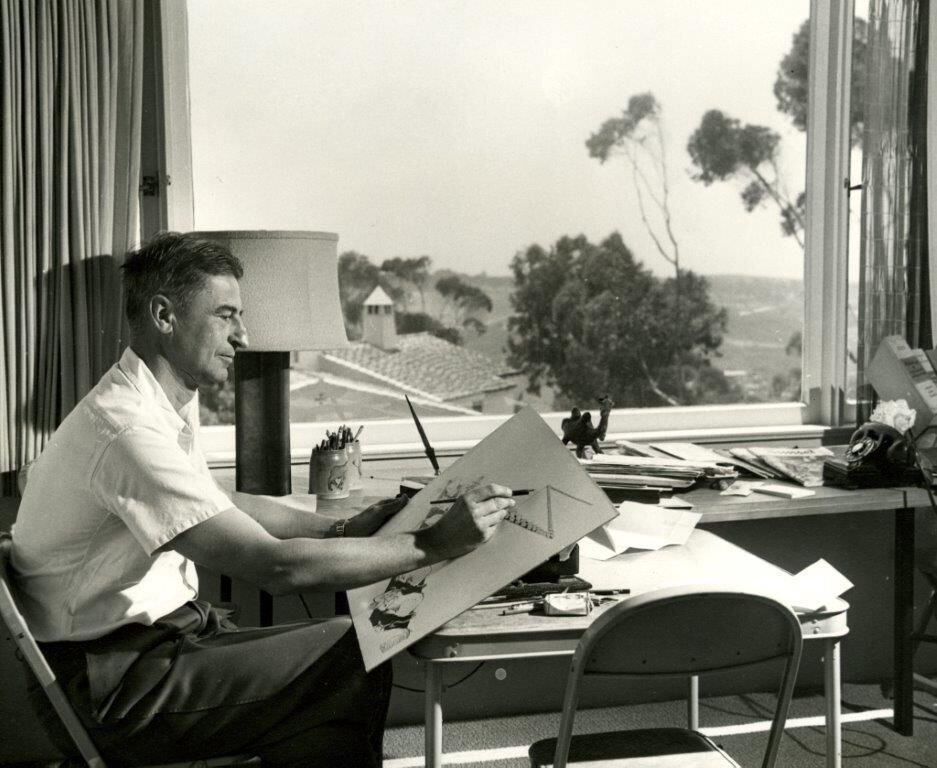

Seuss wrote and illustrated more than 60 books, which have sold over 600 million copies. His most famous, The Cat in the Hat (1957), reveals many of his signature flourishes: a delight in words for their own sake, creating ever more surreal combinations through surprising rhymes; drawings of fantastical figures and complicated inventions; and a questioning of the values and conventions of adults.

|

| Dr Seuss with his book The Cat in the Hat, pictured in 1957 (Credit: Getty) |

Arguing in a 1959 Life magazine interview that “kids can see a moral coming a mile off and they gag at it”, Seuss chose humour over dogmatism. There was a time, however, when he combined the two – and many believe it was during this period that the essential elements of Dr Seuss emerged. The surreal rhyming verse and strange creatures that populated his children’s books – whales with long eyelashes; goats joined at the beard; many-legged cows – find their roots in his World War Two propaganda cartoons.

“Dr Seuss, beloved purveyor of genial rhyming nonsense for beginning readers, stuff about cats in hats and foxes in socks, started as a feisty political cartoonist who exhorted America to do battle with Hitler? Yeah, right!” exclaims Art Spiegelman, the graphic novelist who created Maus, in the foreword to a 1999 book. Historian Richard Minear’s Dr Seuss Goes to War features nearly 200 cartoons that were left unseen for half a century – cartoons that help redraw the beloved king of the kooky.

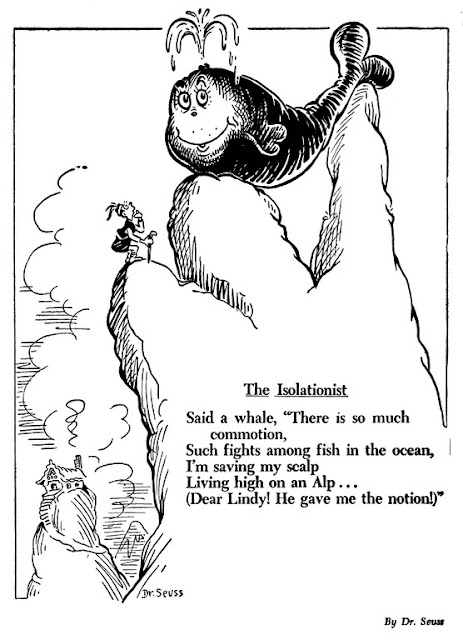

Describing Dr Seuss’s wartime output as “very impressive evidence of cartooning as an art of persuasion”, Spiegelman explains how they “rail against isolationism, racism, and anti-semitism with a conviction and fervor lacking in most other American editorial pages of the period… virtually the only editorial cartoons outside the communist and black press that decried the military’s Jim Crow policies and Charles Lindbergh’s anti-semitism”. Dr Seuss, he argues, “made these drawings with the fire of honest indignation and anger that fuels all real political art”.

Taking sides

Between January 1941 and January 1943, Seuss created more than 400 political cartoons for the left-wing daily New York newspaper PM. He attacked the America First policies espoused by Lindbergh and others, who wanted to prevent the US entering World War Two; he lampooned Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini; and he pleaded for racial tolerance.

The unique galumphing menagerie of Seussian fauna and themes that later enraptured millions… come into focus in these early drawings – Art Spiegelman

Through the cartoons, we can see Seuss “develop his goofily surreal vision while he delivers the ethical goods”, argues Spiegelman. “The unique galumphing menagerie of Seussian fauna, the screwball humor and themes that later enraptured millions… come into focus in these early drawings that were done with urgency on very short deadlines.” According to Minear, most of Seuss’ later books – barring the ones teaching children to read – are political in some way. And they contain features that can be traced back to the wartime cartoons.

One, depicting a whale stranded on a mountain in a parody of American isolationists, later appeared in the 1955 book On Beyond Zebra. Another, showing a cow with many udders to represent conquered European nations being milked by Hitler, also featured in the same book. A cartoon satirising dawdling wartime producers with a teetering tower of turtles was replicated in Seuss’s 1958 book Yertle the Turtle.

|

| Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories, 1958 (Credit: Dr Seuss/Courtesy of Random House Children’s Books) |

That book is itself a political parable. “Not many people know that when he first drew Yertle, it had a Hitler moustache, so Yertle was Hitler,” Richard Minear tells BBC Culture. The story has been seen as poking fun at all despots, with one journalist arguing in 2003 that “its final lines apply as much to Saddam Hussein as they once did to the European fascists”. Another claims that its warning on the dangers of overreaching is an important lesson for business. More recently, critics of rising American nationalism have shared Seuss’ cartoons. The messages in his stories help explain the enduring power of Dr Seuss as much as his humour and poetry.

As Spiegelman argues, the wartime cartoons “make us more aware of the political messages often embedded within the sugar pill of Dr Seuss’s signature zaniness”. While Yertle is an anti-fascist tale, The Sneetches (1953) tells a story about discrimination based on stars worn on the bellies of birds (“what are those stars,” asks Spiegelman, “if not Magen Davids?”).

|

| The Lorax, 1971 (Credit: Dr Seuss/Courtesy of Random House Children’s Books) |

And The Lorax is one of the most powerful environmental fables of the 20th Century. Published in 1971, the year after the celebration of the first Earth Day, it has been described in Nature magazine as “a kind of Silent Spring for the playground set”, teaching generations of children about ecological ruin brought on by greed – and offering lessons for environmental policy today.

Meanwhile, The Butter Battle Book is a parable about arms races, in particular mutually assured destruction – according to Spiegelman, its “polemic for nuclear disarmament… created a blizzard of controversy when it first appeared in 1984”. While reflecting the concerns of the Cold War era, it is also timeless satire: depicting a deadly conflict caused by something trivial, in this case toast, it recalls a war in Gulliver’s Travels sparked by an argument over how to crack an egg.

On the offensive

One problematic issue in Seuss’s wartime cartoons is touched upon in Horton Hears a Who!. “The Japanese cartoons are horribly narrow and racist and stereotyped,” says Minear. A supporter of the mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans, Seuss used offensive stereotypes to caricature the Japanese in his cartoons, leading to accusations that he was racist.

“I think he would find it a legitimate criticism, because I remember talking to him about it at least once and him saying that things were done a certain way back then,” Ted Owens, a great-nephew of Geisel, told The New York Times. “Characterizations were done, and he was a cartoonist and he tended to adopt those. And I know later in his life he was not proud of those at all.”

Seuss followed up a 1976 interview for his former college, Dartmouth, with a handwritten note in which he partially apologised for the cartoons. “When I look at them now they’re hurriedly and embarrassingly badly drawn, and they’re full of many snap judgements that every political cartoonist has to make… The one thing I do like about them, however, is their honesty and their frantic fervor. I believed the USA would go down the drain if we listened to the America Firstisms… I probably was intemperate in my attacks on them. But they almost disarmed this country at a time it was obviously about to be destroyed, and I think I helped a little bit – not much, but some – in stating the fact that we were in a war and we damned well better ought to do something about it.”

According to Minear, Horton Hears a Who! was an apology of sorts for his anti-Japanese cartoons. “It was written soon after the war, and after a visit to Japan. He doesn’t come out and explicitly say he’s recanting his earlier views but it’s a very different take.” The 1954 book is a parable about post-war relations between the US, Japan and the Soviet Union, promoting equal treatment with the line “a person’s a person no matter how small”.

Seuss was engaged in propaganda during his war years; one superior officer described him in an evaluation as a “personable zealot”. As Minear puts it: “He worked for a couple of years with Frank Capra on the Why We Fight series, which is documentary film propaganda. If you look at them now, they’re of a piece with the wartime cartoons.

“He simplified things – that was part of the wartime experience… by the time he came out of World War Two, there was a focus that hadn’t been there before.” It continued into his later children’s books. “The books themselves are in the broader sense propaganda, argument, persuasion.”

I’m subversive as hell! I’ve always had a mistrust of adults… The Cat in the Hat is a revolt against authority – Theodor Seuss Geisel

Although Dr Seuss insisted he never started out with a moral in his children’s stories, he did say “there’s an inherent moral in any story”; often he was able to use humour to mask what could be weighty topics. “He’s a genius that way,” argues Minear. “He was very conscious of what he was doing, what he was trying to do.”

Playground satire

Even The Cat in the Hat had a political edge. In Jonathan Cott’s 1983 collection of interviews, Pipers at the Gates of Dawn, Seuss said in response to the suggestion that some of his books are subversive: “I’m subversive as hell! I’ve always had a mistrust of adults… Hilaire Belloc, whose writings I liked a lot, was a radical. Gulliver’s Travels was subversive, and both Swift and Voltaire influenced me. The Cat in the Hat is a revolt against authority, but it’s ameliorated by the fact that the cat cleans up everything in the end.” Spiegelman finds a precursor to the cat’s red-and-white striped hat in the headgear on the bird Seuss drew to depict the US in his political cartoons.

Seuss himself didn’t necessarily see a huge disconnect between what he was doing during the war and what he did afterwards. “Children’s literature as I write it and as I see it is satire to a great extent – satirizing the mores and the habits of the world,” he is quoted in Cott’s book. “There’s Yertle the Turtle, which was modelled on the rise of Hitler; and then there’s The Sneetches, which was inspired by my opposition to anti-Semitism. These books come from the part of my soul that started out to be a teacher.”

The cartoons offer us a richer understanding of one of the best-selling children’s authors of all time. He revealed, when discussing The Butter Battle Book in a 1984 interview for USA Today: “I don’t think my book is going to change society. But I’m naïve enough to think that society will be changed by examination of ideas through books and the press, and that information can prove to be greater than the dissemination of stupidity.”