Please Note - These are my class notes. I am in the process of reading Eliot with the help of a quarter-term quasi-college community class. These notes might not be correct as I have written them. Please utilize the additional resources I will list here and in other parts of this poetry website as I refer to them. Thanks! - re slater

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

As a Christian, Eliot began to think about the church that was and the church which is. These thoughts produced in him not only a sense of tension but a great sense of disruption both in his own life and the life of the church in the world. A world in which it had failed in its outreach between the voices of old and new theology. Theologies which were either bad or good or were not meeting the needs of humanity in its strifes and confusions. Eliot's own life was similarly filled with its many voices of where the bedrock of faith lay. Did it lay in Jesus' commands to love or in the church's commands which seemed to distance itself from its God, its duties to ministries, and its calls to love rather than to judge and condemn. Such was the turmoil Eliot was dealing with.Secondly, and most importantly, Eliot visited Burnt Norton with his ex-wife, and later, close companion Emily Hale, walking the grounds with him in his memories. Much later, Eliot's second wife, Valarie, captured his thoughts in the play "Cats" when Eliot reflected that "memory is the real parts of us; that memory revises us as we cast about in our thoughts."

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

Burnt Norton was the first of what became four parts, or musical compositions, known as Eliot's "Four Quartets". The other three sections - each having five tonal poems each - were East Coker, The Dry Salvages, and Little Gidding, respectively. These latter three were produced several years after the first composition, Burnt Norton. In essence, Eliot's former life, and all that was in it, had burnt up. After suffering various and sundry griefs as only a poet might do, Eliot picked up its tattered pieces to being to put together his past with his present and where it might lend itself into the flowing streams of humanity's despairs and disillusionments.Further, each composition held differing themes and subject matters but when read within themselves and between themselves the reader will find all themes, matters, and compositions as one tightly interwoven piece across 4x5 orchestrations (4 poems x 5 sections per each poem).

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

Above are the five sections of Burnt Norton which became the five common themes for all preceding sectional poems of "The Four Quartets". One may think of them musically as "movements" between composition lending to the overall musicality of the poems themselves.Here is my own interpretation of Eliot's themes:

- I am an eternal being learning to live in the present-ness of the present

- My experience of present-ness is one of living an existence in crisis

- My existential struggle feels to me as my own dissent into the many hells of the world besides mine own

- I cry out to God moment by moment for help, wisdom, and the ability to love

- I struggle to find and express wholeness through past and present hardships

Conclusion: Every part of Burnt Norton struggles with crisis towards surviving despair and disappointment asking daily the questions of "What now? How do I live with myself or with the things I witness about me in the world, the church, my faith, friends, and family?"

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

"Words beyond words" says Eliot:Our words fail to express what we know, what we see, what we hear, smell, and sense. Poetry attempts the impossible by uttering the inexpressible. It's not enough to say as a Christian, the all is expressed by God in the Incarnation of Christ as the Word or Testament or Covenant or Action of God. Even in God's Word lies the inexpressible. Neither the Author of creation nor creation itself can be written about without our language and senses failing us. The deep mystery of storytelling, or story expressing, is that even the very process wearies the author and poet of the infinite ways to experience and tell of a situation. And yet, as a poet, I am driven to express the inexpressible as only I can, though I feel my own fraility in the very process I attempt. - R.E. Slater

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

The tone of Burnt Norton is that of paradox. Eliot expresses his words in epigrams. By pithy sayings or remarks of an idea he has in a clever or amusing way. His words swim through our heart and soul much like a summer's tornadoey gust of swirling wind we run to catch and stand within before it blows past us quickly expiring on its meandering route.

John 1.1 "In Christ was the Word, the Logos of God" - Eliot takes the universal Logos and particularizes it in creation. Like the Greek philosopher Heraclitus who said "No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man." So Eliot weaves and reweaves time about itself sounding more like the British Process Philosopher Alfred North Whitehead than himself as he looks at time and life to flatly state every moment is unlike the last and will not be like itself in the future. What then, is life all about? And why is life found to be in this way? All fluid in motion, event to event, interacting with itself from itself to become more of itself in restless, ceaseless being and becoming." (sic, process philosophy; and, process theology; both of which may be found in contemporary discussion here, at Relevancy22).

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

Here, the question might be asked of Eliot whether he knew of the contemporary academicians of Einstein and Whitehead. The first, Einstein, who was famous for his Relativity Theory which preceded all future Quantum Physics studies. And the Second, Whitehead, for his "Philosophy of Organism" later to be known as "Process Philosophy" along with its many derivations of process theology, process sciences, the process quantum sciences, neurology, evolution, sociology, psychology, religion, socio-political economic systems, and etc. Each academic knew of the other as friends and fellow Brits in the Royal Academy of Sciences. And both their life works had been recently expressed no more than 15 years ago or there-abouts. Yet whether Eliot was expressing in the Four Quartets his own observations or improving in character his predecessor's observations is moot as Eliot uses these expressions time and again to tell us that he is in a quandary, held in a world which is perplexing, spinning about like the swirling wind attempting to explain his experience with Christ's Word to "Incarnate the World" by acts of love and desperation.Hence, Eliot states that "time is relational" which is what Einstein and Whitehead were saying. Moreover, that ALL things are relational with ALL things whether near or far. Nothing operates alone with an effect/affect on ALL other things. Einstein says "Without matter in motion there can be no time, event, space, or gravity." Whitehead similarly says, "Nothing operates alone. All things are in relation to one another. Our cosmology is ultimately relational."

"All past and future falls to the present." - adaptation: R.E. Slater"Hold to the now, the here, through which all future plunges to the past." - James Joyce (Ulysses)Observation: The eternality of the present-ness of the present presence becomes unredeemable if unused; but redeemable when used in "LIVED" existence. - R.E. Slater

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

Here TSE pictures "motion and growth": The dancer and ice skater; the spinning of the stars; the movement of the moving tree. That we are in the movement of time's motions of stars and seasons and flesh whilst living in an eternal present which passes and begins all at the same time.Eliot speaks to the crosswords of time v eternity: That neither time nor eternity ever is arrested or stops moving; that they are always in ascent and descent; in stasis and then dynamic interleave. We can never be anywhere else but in the here-and-now attempting to work out, to reconcile, our present with its past and future movements to come.As such, our memories, like Eliot's, are trapped in the rose-bed wishing to rise up through the trees into the heavens above. That our dance with life in this life is never suspended or interrupted lest we allow it to be upon momentary horrors lived. We dance with timeful eternities conspiring an immortality of a kind upon the motion of concrete things which harm or still the soul to the motion of concrete things which inspire and drive one forwards in passion, with resoluteness, to rise above the defeats and tragedies, and woes besetting our souls with losses deep and scarring.Living in this life requires doing what we are meant to do and not quitting until it is fulfilled, or passed down, or both. To conquer time is to live timefully in time where past and future are gathered, in reconciliation within ourselves. And from a Christian standpoint, that justice will be met, and love and hope be reborn again, despite all which strives against living by undoing living life's from their purposes and wills.

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

Eliot continues his descent into darkness in section 3. He speaks to his perpetual solitude, destitution, desiccation, evacuation, and inoperancy gained from living in the world with dashed hopes, harm, and poor choices. Choices which plague him. Which have unmade him in his considerations of whether he should have, or shouldn't have done this thing or that thing. Of the wrongs he has done and the rights he had missed to correct opportunities in time.

But then he thinks to himself that when finally recognizing what his life has spent of itself, has made of itself, has missed in this or that department, that he cannot live like this, driving himself crazy in his penitence of soul and heart. But that this very process of repenting, of being emptied of one's self is the very process of death which becomes ironically very life itself.As the Magi had once said of the baby Jesus they had beheld, "This birth was like unto our own death!" No truer words were spoken to the state of mankind dead to itself with no life. That in the paradox of things, to die is to live, and for the Magi, their death to self in its myriad ways of unlove, unforgiveness, ungiving, can only be righted in recognizing the love of God who is ever constant in loving, forgiving, and giving of the divine Self to the needs of a mortal creation blackened and gone mad by sin. That without self-diminishment (not in the ascetic, monkish kind of way of self-deprecation), without undergoing the internal, personal processes of self-emptying of one's deadened life, one cannot live. And it is in the Christ child wherein life is found again in its death. Where hope and love may be birthed again - not only in the renewal of penitence but in the renewal of the human spirit by divine means of grace and reclamation power.Humanity therefore is always in the process of eternally dying to itself but also always in the process of being emptied out of itself whether by laments or hurts or the scars which it bears. For Eliot, as for his new Christian faith, the way down is also the way up. And its is this aspect of eternally becoming within his broken being which aspires him to rise up, to reconcile with his regrets and harms, to return back to his identity and purpose in the adolescence of his being bound by a new self-awareness released from his darkness to live in the light of being and becoming.

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

TSE begins his ascent up from the death of self. First, by recognizing that we live in the here-and-now. And secondly, by recognizing that when we are emptied of ourself we are rid of the things which hold us back from new-birth-living. One might say this is an "Elergy to Ascent" or "Ascending" from the grave of self-and-world towards light and life. "The light is still at the still point of the turning world." We who have died as living beings have been stilled in our hearts and minds to consider the turning world in its glories, its vanities, its sobering realities, its harsh melting points, and may rise like the kingfisher's wing unstilled in the light against the darkness which might still it to its duties, needs, arousals, passions, and very being of its soul to become.

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

Here, in section 5, Eliot wrestles with speaking about his relationship with life, with Vivien, Emily, etc, as well as life's elements - especially of his close relationships - with himself. Of how their worlds intersected with his, clashed with his, made peace with his, as he with them. To learn to speak of beingness in an infinite sense of processual development, growth, maturation, pursuit, of never-ceasing beginnings and endings, both in life's deathly sense and life's atoning redemptive senses.Overall, Eliot expresses in his worldly and personal weariness, hope. He is learning to live together with himself when filled with joy or sadness. That within his melancholy heart of existence there may be overall goodness merging in-and-out with times of wasted possibilities. In a sense, Eliot is seeking a restitution within himself, or a permission, to live in a broken world, as a broken (time-ful) being himself, in recognition that life's truer modes stretch endlessly with generative, valuative possibilities. An infinite arrangement of these should mankind find within itself the ability to become humble with nature, each other, and within oneself. If not, we war with all - and especially ourselves - as restlessly as we might coexist in goodness and love with one another - and ourselves. These then are the mysteries of life.

|

| @copyright Dr. Michael Stevens - all rights reserved |

‘Burnt Norton’ is the first poem in Four Quartets. Although it was first published in 1936, the poem appeared together with the rest of the quartets in 1943. Four Quartets includes four poems that were independently published over six years: ‘Burnt Norton’, ‘East Coker’, ‘The Dry Salvages’, and ‘Little Gidding’. T. S. Eliot believed that Four Quartets was his best work. These poems explore the relationship between men and time, the need for spirituality, the importance of consciousness and existence, among other themes.

Sections of Burnt Norton

‘Burnt Norton’ has 178 lines and can be found in full, along with the rest of the Quartets, here. The poem, like East Coker, The Dry Salvages, and Little Gidding, is divided into five sections. The first section focuses on the movement of time, while the second section explores the unsatisfying worldly experience. The third section introduces a possible purgation of the modern world, which contrasts with the lyric prayer of the fourth section. Finally, the fifth section presents the question of art’s possible entirety, which is equivalent to the seek for spiritual health. The poem is named after a manor house in Gloucestershire.

Theme of Burnt Norton

The main theme of ‘Burnt Norton is the nature of time, its relation to salvation, and the contrast between the experience of the modern man and spirituality. The lyrical voice meditates on life and the need to subscribe to the universal order. The poem’s structure and form are similar to T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, as several fragments of poetry are put together and set as one. The rhyme and meter rely on the repetition and circularity of language, which corresponds to the conception of time introduced in the poem. Light and dark, movement and stillness, and roses are some of the motifs that appear in ‘Burnt Norton’.

You can read the full poem here and more poems by T.S. Eliot here.

Analysis of Burnt Norton

Section One

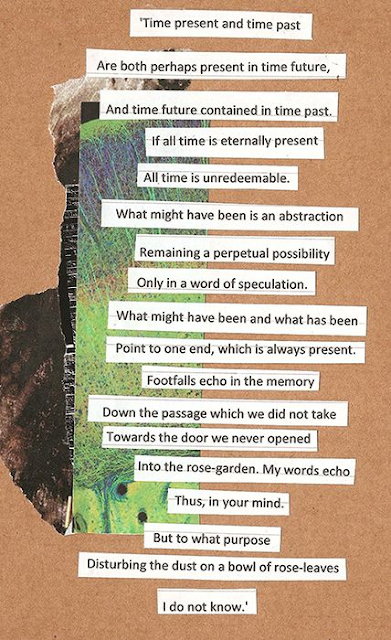

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable […]

The first section of ‘Burnt Norton’ presents, on the one hand, a particular conception of time: “If all time is eternally present/All time is unredeemable”. The different temporalities of time are related to each other, as past and future are always implicated in the present. Through this conception of time, the lyrical voice explores the possibility that men can only control the present. This section also explores an alternate temporality (“Down the passage which we did not take/Towards the door we never opened/Into the rose-garden”) that, as the ending of the section suggests, is also part of the present: “What might have been and what has been/Point to one end, which is always present”.

On the other hand, the poem describes a rose garden, which is navigated by the lyrical voice. A bird works as a guide through the garden shows the lyrical voice around and asks him/her to look for the laughing children: “Quick, said the bird, find them, find them,/Round the corner”. The rose-garden is a symbolic place, as it evokes the Garden of Eden. This can be related to the author’s relation to Christianity and how it is manifested in different moments in the Four Quartets. The garden also shows signs of human presence and neglect: “Then a cloud passed, and the pool was empty”. This idea of ruin will also come out in the lyrical voice’s mention of modernity.

Section Two

Garlic and sapphires in the mud

Clot the bedded axle-tree.

The trilling wire in the blood

Sings below inveterate scars

Appeasing long forgotten wars […]

The second section opens with irregular tetrameters, forming an embedded poem. This shorter poem connects unusual images (“Garlic and sapphires in the mud/Clot the bedded axle-tree”), which are “reconciled among the stars”. Although these images appear pagan to a certain extent, the relationship between them anticipates the theme of unity found in Four Quartets. This can also be read as an acknowledgment of the fragmentary nature of modernity.

Then, the poem changes its form and focuses on a meditation of consciousness and living (“Time past and time future/Allow but a little consciousness./To be conscious is not to be in time”) that goes back to the idea of coexisting temporalities in the present: “To be conscious is not to be in time”. The lyrical voice reflects on how to live in only one temporality when time is always changing (“I can only say, there we have been: but I cannot say where./And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time”). Consciousness, as opposed to time, is fixed but enables memory: But only in time can the moment in the rose-garden […]/Be remembered”. Note how the image of the rose-garden appears once again and how this section, as the previous one, is filled with images of nature.

Section Three

Here is a place of disaffection

Time before and time after

In a dim light: neither daylight

Investing form with lucid stillness

Turning shadow into transient beauty

Wtih slow rotation suggesting permanence […]

The third section of Burn Norton focuses on one moment: “a place of disaffection”. This place is linked to every day, which “Neither plentitude nor vacancy” can be found, and the modern life, where there is no transcendence (“Nor darkness to purify the soul”), no meaning (“Filled with fancies and empty of meaning”) and no beauty (“Turning shadow into transient beauty”). The lyrical voice relates to this modern world and self with numbness and lack of spirituality. Notice how this is emphasized by the use of repeated structures and words: “Dessication of the world of sense,/Evacuation of the world of fancy,/Inoperancy of the world of spirit;”. This is contrasted by the movement of time (“while the world moves”) that has been developed and detailed in the previous sections.

Section Four

Time and the bell have buried the day,

the black cloud carries the sun away.

Will the sunflower turn to us, will the clematis

Stray down, bend to us; tendril and spray

Clutch and cling?

The fourth section has only 10 lines and it focuses on the description and movement of time. Again, there are many images of nature that resemble the rose-garden in the first section. The image of the yew (“Fingers of yew be curled /Down on us?”) that belongs to the yew tree, also known as the “tree of death”, brings the possibility of a spiritual rebirth, which is, later, discarded by the lyrical voice. Notice that this short section establishes a sort of melody, as some of the lines rhyme, which is accompanied by the different lengths of the lines through the stanza that concentrates on the word “chill” that stands alone in the middle. This emphasizes the coldness of modern spirituality.

Section Five

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence. Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach

The stillness, as a Chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness […]

The fifth section of ‘Burnt Norton’ goes back to images and themes that were introduced in previous sections of the poem. The movement of time and how it can be addressed is again mentioned: “Words move, music moves/ Only in time”. Yet, the fixed point presented in this section is not related to every day as in the third section but to death: “Words, after speech, reach/Into the silence. Only by the form, the pattern,/Can words or music reach/The stillness, as a Chinese jar still/Moves perpetually in its stillness”. Thus, there is a paradox presented regarding time here, as the constant movement mentioned at the beginning and the stillness mentioned in this section seem opposite. In that sense, the lyrical voice mentions that desire would be similar to the constant movement among temporalities (“Desire itself is movement”), whereas love is closer to stillness (“Love is itself unmoving”). Love, as the relation of the themes and the poems itself to Christianity suggests, is related to religion and devotion, and it is a central element for remaining conscious and present.

This section also addresses art (“Words move, music moves”), its relation to time, and its capacity to become eternal, and it can be related to the image of the Chinese jar. Moreover, this image is a clear reference to Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, as the jar represents the capacity of transcending the moment and times itself. According to the lyrical voice, “words, after speech, reach/Into the silence” and poetic form, like the stillness of the Chinese jar, can resemble something eternal in its present state.

The final lines of the poems return to the laughing children in the rose-garden, asserting the circularity of the poem: “There rises the hidden laughter/Of children in the foliage”. Yet, the laugher becomes a mocking laugher, related to the enslavement of modernity.