To Henry St. John, Lord Bolingbroke

Awake, my St. John! leave all meaner things

To low ambition, and the pride of kings.

Let us (since life can little more supply

Than just to look about us and to die)

Expatiate free o'er all this scene of man;

A mighty maze! but not without a plan;

A wild, where weeds and flow'rs promiscuous shoot;

Or garden, tempting with forbidden fruit.

Together let us beat this ample field,

Try what the open, what the covert yield;

The latent tracts, the giddy heights explore

Of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar;

Eye Nature's walks, shoot folly as it flies,

And catch the manners living as they rise;

Laugh where we must, be candid where we can;

But vindicate the ways of God to man.

I.

Say first, of God above, or man below,

What can we reason, but from what we know?

Of man what see we, but his station here,

From which to reason, or to which refer?

Through worlds unnumber'd though the God be known,

'Tis ours to trace him only in our own.

He, who through vast immensity can pierce,

See worlds on worlds compose one universe,

Observe how system into system runs,

What other planets circle other suns,

What varied being peoples ev'ry star,

May tell why Heav'n has made us as we are.

But of this frame the bearings, and the ties,

The strong connections, nice dependencies,

Gradations just, has thy pervading soul

Look'd through? or can a part contain the whole?

Is the great chain, that draws all to agree,

And drawn supports, upheld by God, or thee?

II.

Presumptuous man! the reason wouldst thou find,

Why form'd so weak, so little, and so blind?

First, if thou canst, the harder reason guess,

Why form'd no weaker, blinder, and no less!

Ask of thy mother earth, why oaks are made

Taller or stronger than the weeds they shade?

Or ask of yonder argent fields above,

Why Jove's satellites are less than Jove?

Of systems possible, if 'tis confest

That Wisdom infinite must form the best,

Where all must full or not coherent be,

And all that rises, rise in due degree;

Then, in the scale of reas'ning life, 'tis plain

There must be somewhere, such a rank as man:

And all the question (wrangle e'er so long)

Is only this, if God has plac'd him wrong?

Respecting man, whatever wrong we call,

May, must be right, as relative to all.

In human works, though labour'd on with pain,

A thousand movements scarce one purpose gain;

In God's, one single can its end produce;

Yet serves to second too some other use.

So man, who here seems principal alone,

Perhaps acts second to some sphere unknown,

Touches some wheel, or verges to some goal;

'Tis but a part we see, and not a whole.

When the proud steed shall know why man restrains

His fiery course, or drives him o'er the plains:

When the dull ox, why now he breaks the clod,

Is now a victim, and now Egypt's God:

Then shall man's pride and dulness comprehend

His actions', passions', being's, use and end;

Why doing, suff'ring, check'd, impell'd; and why

This hour a slave, the next a deity.

Then say not man's imperfect, Heav'n in fault;

Say rather, man's as perfect as he ought:

His knowledge measur'd to his state and place,

His time a moment, and a point his space.

If to be perfect in a certain sphere,

What matter, soon or late, or here or there?

The blest today is as completely so,

As who began a thousand years ago.

III.

Heav'n from all creatures hides the book of fate,

All but the page prescrib'd, their present state:

From brutes what men, from men what spirits know:

Or who could suffer being here below?

The lamb thy riot dooms to bleed today,

Had he thy reason, would he skip and play?

Pleas'd to the last, he crops the flow'ry food,

And licks the hand just rais'd to shed his blood.

Oh blindness to the future! kindly giv'n,

That each may fill the circle mark'd by Heav'n:

Who sees with equal eye, as God of all,

A hero perish, or a sparrow fall,

Atoms or systems into ruin hurl'd,

And now a bubble burst, and now a world.

Hope humbly then; with trembling pinions soar;

Wait the great teacher Death; and God adore!

What future bliss, he gives not thee to know,

But gives that hope to be thy blessing now.

Hope springs eternal in the human breast:

Man never is, but always to be blest:

The soul, uneasy and confin'd from home,

Rests and expatiates in a life to come.

Lo! the poor Indian, whose untutor'd mind

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind;

His soul, proud science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk, or milky way;

Yet simple nature to his hope has giv'n,

Behind the cloud-topt hill, an humbler heav'n;

Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd,

Some happier island in the wat'ry waste,

Where slaves once more their native land behold,

No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold.

To be, contents his natural desire,

He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire;

But thinks, admitted to that equal sky,

His faithful dog shall bear him company.

IV.

Go, wiser thou! and, in thy scale of sense

Weigh thy opinion against Providence;

Call imperfection what thou fanciest such,

Say, here he gives too little, there too much:

Destroy all creatures for thy sport or gust,

Yet cry, if man's unhappy, God's unjust;

If man alone engross not Heav'n's high care,

Alone made perfect here, immortal there:

Snatch from his hand the balance and the rod,

Rejudge his justice, be the God of God.

In pride, in reas'ning pride, our error lies;

All quit their sphere, and rush into the skies.

Pride still is aiming at the blest abodes,

Men would be angels, angels would be gods.

Aspiring to be gods, if angels fell,

Aspiring to be angels, men rebel:

And who but wishes to invert the laws

Of order, sins against th' Eternal Cause.

V.

Ask for what end the heav'nly bodies shine,

Earth for whose use? Pride answers, " 'Tis for mine:

For me kind Nature wakes her genial pow'r,

Suckles each herb, and spreads out ev'ry flow'r;

Annual for me, the grape, the rose renew,

The juice nectareous, and the balmy dew;

For me, the mine a thousand treasures brings;

For me, health gushes from a thousand springs;

Seas roll to waft me, suns to light me rise;

My foot-stool earth, my canopy the skies."

But errs not Nature from this gracious end,

From burning suns when livid deaths descend,

When earthquakes swallow, or when tempests sweep

Towns to one grave, whole nations to the deep?

"No, ('tis replied) the first Almighty Cause

Acts not by partial, but by gen'ral laws;

Th' exceptions few; some change since all began:

And what created perfect?"—Why then man?

If the great end be human happiness,

Then Nature deviates; and can man do less?

As much that end a constant course requires

Of show'rs and sunshine, as of man's desires;

As much eternal springs and cloudless skies,

As men for ever temp'rate, calm, and wise.

If plagues or earthquakes break not Heav'n's design,

Why then a Borgia, or a Catiline?

Who knows but he, whose hand the lightning forms,

Who heaves old ocean, and who wings the storms,

Pours fierce ambition in a Cæsar's mind,

Or turns young Ammon loose to scourge mankind?

From pride, from pride, our very reas'ning springs;

Account for moral, as for nat'ral things:

Why charge we Heav'n in those, in these acquit?

In both, to reason right is to submit.

Better for us, perhaps, it might appear,

Were there all harmony, all virtue here;

That never air or ocean felt the wind;

That never passion discompos'd the mind.

But ALL subsists by elemental strife;

And passions are the elements of life.

The gen'ral order, since the whole began,

Is kept in nature, and is kept in man.

VI.

What would this man? Now upward will he soar,

And little less than angel, would be more;

Now looking downwards, just as griev'd appears

To want the strength of bulls, the fur of bears.

Made for his use all creatures if he call,

Say what their use, had he the pow'rs of all?

Nature to these, without profusion, kind,

The proper organs, proper pow'rs assign'd;

Each seeming want compensated of course,

Here with degrees of swiftness, there of force;

All in exact proportion to the state;

Nothing to add, and nothing to abate.

Each beast, each insect, happy in its own:

Is Heav'n unkind to man, and man alone?

Shall he alone, whom rational we call,

Be pleas'd with nothing, if not bless'd with all?

The bliss of man (could pride that blessing find)

Is not to act or think beyond mankind;

No pow'rs of body or of soul to share,

But what his nature and his state can bear.

Why has not man a microscopic eye?

For this plain reason, man is not a fly.

Say what the use, were finer optics giv'n,

T' inspect a mite, not comprehend the heav'n?

Or touch, if tremblingly alive all o'er,

To smart and agonize at ev'ry pore?

Or quick effluvia darting through the brain,

Die of a rose in aromatic pain?

If nature thunder'd in his op'ning ears,

And stunn'd him with the music of the spheres,

How would he wish that Heav'n had left him still

The whisp'ring zephyr, and the purling rill?

Who finds not Providence all good and wise,

Alike in what it gives, and what denies?

VII.

Far as creation's ample range extends,

The scale of sensual, mental pow'rs ascends:

Mark how it mounts, to man's imperial race,

From the green myriads in the peopled grass:

What modes of sight betwixt each wide extreme,

The mole's dim curtain, and the lynx's beam:

Of smell, the headlong lioness between,

And hound sagacious on the tainted green:

Of hearing, from the life that fills the flood,

To that which warbles through the vernal wood:

The spider's touch, how exquisitely fine!

Feels at each thread, and lives along the line:

In the nice bee, what sense so subtly true

From pois'nous herbs extracts the healing dew:

How instinct varies in the grov'lling swine,

Compar'd, half-reas'ning elephant, with thine:

'Twixt that, and reason, what a nice barrier;

For ever sep'rate, yet for ever near!

Remembrance and reflection how allied;

What thin partitions sense from thought divide:

And middle natures, how they long to join,

Yet never pass th' insuperable line!

Without this just gradation, could they be

Subjected, these to those, or all to thee?

The pow'rs of all subdu'd by thee alone,

Is not thy reason all these pow'rs in one?

VIII.

See, through this air, this ocean, and this earth,

All matter quick, and bursting into birth.

Above, how high, progressive life may go!

Around, how wide! how deep extend below!

Vast chain of being, which from God began,

Natures ethereal, human, angel, man,

Beast, bird, fish, insect! what no eye can see,

No glass can reach! from infinite to thee,

From thee to nothing!—On superior pow'rs

Were we to press, inferior might on ours:

Or in the full creation leave a void,

Where, one step broken, the great scale's destroy'd:

From nature's chain whatever link you strike,

Tenth or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike.

And, if each system in gradation roll

Alike essential to th' amazing whole,

The least confusion but in one, not all

That system only, but the whole must fall.

Let earth unbalanc'd from her orbit fly,

Planets and suns run lawless through the sky;

Let ruling angels from their spheres be hurl'd,

Being on being wreck'd, and world on world;

Heav'n's whole foundations to their centre nod,

And nature tremble to the throne of God.

All this dread order break—for whom? for thee?

Vile worm!—Oh madness, pride, impiety!

IX.

What if the foot ordain'd the dust to tread,

Or hand to toil, aspir'd to be the head?

What if the head, the eye, or ear repin'd

To serve mere engines to the ruling mind?

Just as absurd for any part to claim

To be another, in this gen'ral frame:

Just as absurd, to mourn the tasks or pains,

The great directing Mind of All ordains.

All are but parts of one stupendous whole,

Whose body Nature is, and God the soul;

That, chang'd through all, and yet in all the same,

Great in the earth, as in th' ethereal frame,

Warms in the sun, refreshes in the breeze,

Glows in the stars, and blossoms in the trees,

Lives through all life, extends through all extent,

Spreads undivided, operates unspent,

Breathes in our soul, informs our mortal part,

As full, as perfect, in a hair as heart;

As full, as perfect, in vile man that mourns,

As the rapt seraph that adores and burns;

To him no high, no low, no great, no small;

He fills, he bounds, connects, and equals all.

X.

Cease then, nor order imperfection name:

Our proper bliss depends on what we blame.

Know thy own point: This kind, this due degree

Of blindness, weakness, Heav'n bestows on thee.

Submit.—In this, or any other sphere,

Secure to be as blest as thou canst bear:

Safe in the hand of one disposing pow'r,

Or in the natal, or the mortal hour.

All nature is but art, unknown to thee;

All chance, direction, which thou canst not see;

All discord, harmony, not understood;

All partial evil, universal good:

And, spite of pride, in erring reason's spite,

One truth is clear, Whatever is, is right.

|

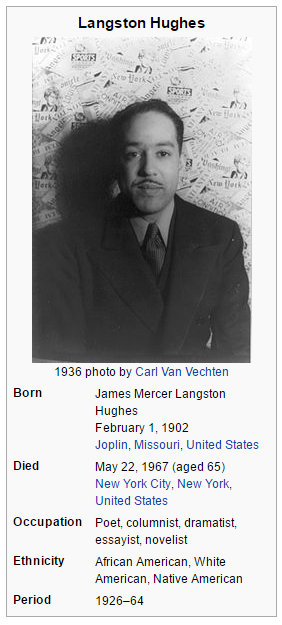

| Alexander Pope as a young man |

An Essay on Man: Epistle II

Related Poem Content Details

I.

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is man.

Plac'd on this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise, and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the stoic's pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest;

In doubt to deem himself a god, or beast;

In doubt his mind or body to prefer;

Born but to die, and reas'ning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such,

Whether he thinks too little, or too much:

Chaos of thought and passion, all confus'd;

Still by himself abus'd, or disabus'd;

Created half to rise, and half to fall;

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurl'd:

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!

Go, wondrous creature! mount where science guides,

Go, measure earth, weigh air, and state the tides;

Instruct the planets in what orbs to run,

Correct old time, and regulate the sun;

Go, soar with Plato to th' empyreal sphere,

To the first good, first perfect, and first fair;

Or tread the mazy round his follow'rs trod,

And quitting sense call imitating God;

As Eastern priests in giddy circles run,

And turn their heads to imitate the sun.

Go, teach Eternal Wisdom how to rule—

Then drop into thyself, and be a fool!

Superior beings, when of late they saw

A mortal Man unfold all Nature's law,

Admir'd such wisdom in an earthly shape,

And showed a Newton as we shew an Ape.

Could he, whose rules the rapid comet bind,

Describe or fix one movement of his mind?

Who saw its fires here rise, and there descend,

Explain his own beginning, or his end?

Alas what wonder! Man's superior part

Uncheck'd may rise, and climb from art to art;

But when his own great work is but begun,

What Reason weaves, by Passion is undone.

Trace science then, with modesty thy guide;

First strip off all her equipage of pride;

Deduct what is but vanity, or dress,

Or learning's luxury, or idleness;

Or tricks to show the stretch of human brain,

Mere curious pleasure, or ingenious pain;

Expunge the whole, or lop th' excrescent parts

Of all our Vices have created Arts;

Then see how little the remaining sum,

Which serv'd the past, and must the times to come!

II.

Two principles in human nature reign;

Self-love, to urge, and reason, to restrain;

Nor this a good, nor that a bad we call,

Each works its end, to move or govern all:

And to their proper operation still,

Ascribe all good; to their improper, ill.

Self-love, the spring of motion, acts the soul;

Reason's comparing balance rules the whole.

Man, but for that, no action could attend,

And but for this, were active to no end:

Fix'd like a plant on his peculiar spot,

To draw nutrition, propagate, and rot;

Or, meteor-like, flame lawless through the void,

Destroying others, by himself destroy'd.

Most strength the moving principle requires;

Active its task, it prompts, impels, inspires.

Sedate and quiet the comparing lies,

Form'd but to check, delib'rate, and advise.

Self-love still stronger, as its objects nigh;

Reason's at distance, and in prospect lie:

That sees immediate good by present sense;

Reason, the future and the consequence.

Thicker than arguments, temptations throng,

At best more watchful this, but that more strong.

The action of the stronger to suspend,

Reason still use, to reason still attend.

Attention, habit and experience gains;

Each strengthens reason, and self-love restrains.

Let subtle schoolmen teach these friends to fight,

More studious to divide than to unite,

And grace and virtue, sense and reason split,

With all the rash dexterity of wit:

Wits, just like fools, at war about a name,

Have full as oft no meaning, or the same.

Self-love and reason to one end aspire,

Pain their aversion, pleasure their desire;

But greedy that its object would devour,

This taste the honey, and not wound the flow'r:

Pleasure, or wrong or rightly understood,

Our greatest evil, or our greatest good.

III.

Modes of self-love the passions we may call:

'Tis real good, or seeming, moves them all:

But since not every good we can divide,

And reason bids us for our own provide;

Passions, though selfish, if their means be fair,

List under reason, and deserve her care;

Those, that imparted, court a nobler aim,

Exalt their kind, and take some virtue's name.

In lazy apathy let Stoics boast

Their virtue fix'd, 'tis fix'd as in a frost;

Contracted all, retiring to the breast;

But strength of mind is exercise, not rest:

The rising tempest puts in act the soul,

Parts it may ravage, but preserves the whole.

On life's vast ocean diversely we sail,

Reason the card, but passion is the gale;

Nor God alone in the still calm we find,

He mounts the storm, and walks upon the wind.

Passions, like elements, though born to fight,

Yet, mix'd and soften'd, in his work unite:

These 'tis enough to temper and employ;

But what composes man, can man destroy?

Suffice that reason keep to nature's road,

Subject, compound them, follow her and God.

Love, hope, and joy, fair pleasure's smiling train,

Hate, fear, and grief, the family of pain,

These mix'd with art, and to due bounds confin'd,

Make and maintain the balance of the mind:

The lights and shades, whose well accorded strife

Gives all the strength and colour of our life.

Pleasures are ever in our hands or eyes,

And when in act they cease, in prospect, rise:

Present to grasp, and future still to find,

The whole employ of body and of mind.

All spread their charms, but charm not all alike;

On diff'rent senses diff'rent objects strike;

Hence diff'rent passions more or less inflame,

As strong or weak, the organs of the frame;

And hence one master passion in the breast,

Like Aaron's serpent, swallows up the rest.

As man, perhaps, the moment of his breath,

Receives the lurking principle of death;

The young disease, that must subdue at length,

Grows with his growth, and strengthens with his strength:

So, cast and mingled with his very frame,

The mind's disease, its ruling passion came;

Each vital humour which should feed the whole,

Soon flows to this, in body and in soul.

Whatever warms the heart, or fills the head,

As the mind opens, and its functions spread,

Imagination plies her dang'rous art,

And pours it all upon the peccant part.

Nature its mother, habit is its nurse;

Wit, spirit, faculties, but make it worse;

Reason itself but gives it edge and pow'r;

As Heav'n's blest beam turns vinegar more sour.

We, wretched subjects, though to lawful sway,

In this weak queen some fav'rite still obey:

Ah! if she lend not arms, as well as rules,

What can she more than tell us we are fools?

Teach us to mourn our nature, not to mend,

A sharp accuser, but a helpless friend!

Or from a judge turn pleader, to persuade

The choice we make, or justify it made;

Proud of an easy conquest all along,

She but removes weak passions for the strong:

So, when small humours gather to a gout,

The doctor fancies he has driv'n them out.

Yes, nature's road must ever be preferr'd;

Reason is here no guide, but still a guard:

'Tis hers to rectify, not overthrow,

And treat this passion more as friend than foe:

A mightier pow'r the strong direction sends,

And sev'ral men impels to sev'ral ends.

Like varying winds, by other passions toss'd,

This drives them constant to a certain coast.

Let pow'r or knowledge, gold or glory, please,

Or (oft more strong than all) the love of ease;

Through life 'tis followed, ev'n at life's expense;

The merchant's toil, the sage's indolence,

The monk's humility, the hero's pride,

All, all alike, find reason on their side.

Th' eternal art educing good from ill,

Grafts on this passion our best principle:

'Tis thus the mercury of man is fix'd,

Strong grows the virtue with his nature mix'd;

The dross cements what else were too refin'd,

And in one interest body acts with mind.

As fruits, ungrateful to the planter's care,

On savage stocks inserted, learn to bear;

The surest virtues thus from passions shoot,

Wild nature's vigor working at the root.

What crops of wit and honesty appear

From spleen, from obstinacy, hate, or fear!

See anger, zeal and fortitude supply;

Ev'n av'rice, prudence; sloth, philosophy;

Lust, through some certain strainers well refin'd,

Is gentle love, and charms all womankind;

Envy, to which th' ignoble mind's a slave,

Is emulation in the learn'd or brave;

Nor virtue, male or female, can we name,

But what will grow on pride, or grow on shame.

Thus nature gives us (let it check our pride)

The virtue nearest to our vice allied:

Reason the byass turns to good from ill,

And Nero reigns a Titus, if he will.

The fiery soul abhorr'd in Catiline,

In Decius charms, in Curtius is divine:

The same ambition can destroy or save,

And make a patriot as it makes a knave.

IV.

This light and darkness in our chaos join'd,

What shall divide? The God within the mind.

Extremes in nature equal ends produce,

In man they join to some mysterious use;

Though each by turns the other's bound invade,

As, in some well-wrought picture, light and shade,

And oft so mix, the diff'rence is too nice

Where ends the virtue, or begins the vice.

Fools! who from hence into the notion fall,

That vice or virtue there is none at all.

If white and black blend, soften, and unite

A thousand ways, is there no black or white?

Ask your own heart, and nothing is so plain;

'Tis to mistake them, costs the time and pain.

V.

Vice is a monster of so frightful mien,

As, to be hated, needs but to be seen;

Yet seen too oft, familiar with her face,

We first endure, then pity, then embrace.

But where th' extreme of vice, was ne'er agreed:

Ask where's the North? at York, 'tis on the Tweed;

In Scotland, at the Orcades; and there,

At Greenland, Zembla, or the Lord knows where:

No creature owns it in the first degree,

But thinks his neighbour farther gone than he!

Ev'n those who dwell beneath its very zone,

Or never feel the rage, or never own;

What happier natures shrink at with affright,

The hard inhabitant contends is right.

VI.

Virtuous and vicious ev'ry man must be,

Few in th' extreme, but all in the degree;

The rogue and fool by fits is fair and wise;

And ev'n the best, by fits, what they despise.

'Tis but by parts we follow good or ill,

For, vice or virtue, self directs it still;

Each individual seeks a sev'ral goal;

But heav'n's great view is one, and that the whole:

That counterworks each folly and caprice;

That disappoints th' effect of ev'ry vice;

That, happy frailties to all ranks applied,

Shame to the virgin, to the matron pride,

Fear to the statesman, rashness to the chief,

To kings presumption, and to crowds belief,

That, virtue's ends from vanity can raise,

Which seeks no int'rest, no reward but praise;

And build on wants, and on defects of mind,

The joy, the peace, the glory of mankind.

Heav'n forming each on other to depend,

A master, or a servant, or a friend,

Bids each on other for assistance call,

'Till one man's weakness grows the strength of all.

Wants, frailties, passions, closer still ally

The common int'rest, or endear the tie:

To these we owe true friendship, love sincere,

Each home-felt joy that life inherits here;

Yet from the same we learn, in its decline,

Those joys, those loves, those int'rests to resign;

Taught half by reason, half by mere decay,

To welcome death, and calmly pass away.

Whate'er the passion, knowledge, fame, or pelf,

Not one will change his neighbour with himself.

The learn'd is happy nature to explore,

The fool is happy that he knows no more;

The rich is happy in the plenty giv'n,

The poor contents him with the care of heav'n.

See the blind beggar dance, the cripple sing,

The sot a hero, lunatic a king;

The starving chemist in his golden views

Supremely blest, the poet in his Muse.

See some strange comfort ev'ry state attend,

And pride bestow'd on all, a common friend;

See some fit passion ev'ry age supply,

Hope travels through, nor quits us when we die.

Behold the child, by nature's kindly law,

Pleas'd with a rattle, tickl'd with a straw:

Some livelier plaything gives his youth delight,

A little louder, but as empty quite:

Scarfs, garters, gold, amuse his riper stage,

And beads and pray'r books are the toys of age:

Pleas'd with this bauble still, as that before;

'Till tir'd he sleeps, and life's poor play is o'er!

Meanwhile opinion gilds with varying rays

Those painted clouds that beautify our days;

Each want of happiness by hope supplied,

And each vacuity of sense by Pride:

These build as fast as knowledge can destroy;

In folly's cup still laughs the bubble, joy;

One prospect lost, another still we gain;

And not a vanity is giv'n in vain;

Ev'n mean self-love becomes, by force divine,

The scale to measure others' wants by thine.

See! and confess, one comfort still must rise,

'Tis this: Though man's a fool, yet God is wise.

What Does the Poem Mean?

Wikipedia - An Essay on Man

An Essay on Man is a poem published by Alexander Pope in 1733-1734. It is an effort to rationalize or rather "vindicate the ways of God to man" (l.16), a variation of John Milton's claim in the opening lines of Paradise Lost, that he will "justify the ways of God to men" (1.26). It is concerned with the natural order God has decreed for man. Because man cannot know God's purposes, he cannot complain about his position in the Great Chain of Being (ll.33-34) and must accept that "Whatever IS, is RIGHT" (l.292), a theme that was satirized by Voltaire in Candide (1759). More than any other work, it popularized optimistic philosophy throughout England and the rest of Europe.

Pope's Essay on Man and Moral Epistles were designed to be the parts of a system of ethics which he wanted to express in poetry. Moral Epistles has been known under various other names including Ethic Epistles and Moral Essays.

On its publication, An Essay on Man received great admiration throughout Europe. Voltaire called it "the most beautiful, the most useful, the most sublime didactic poem ever written in any language". In 1756 Rousseau wrote to Voltaire admiring the poem and saying that it "softens my ills and brings me patience". Kant was fond of the poem and would recite long passages from it to his students.

Later however, Voltaire renounced his admiration for Pope's and Leibniz's optimism and even wrote a novel, Candide, as a satire on their philosophy of ethics. Rousseau also critiqued the work, questioning "Pope's uncritical assumption that there must be an unbroken chain of being all the way from inanimate matter up to God."

The essay, written in heroic couplets, comprises four epistles. Pope began work on it in 1729, and had finished the first three by 1731. They appeared in early 1733, with the fourth epistle published the following year. The poem was originally published anonymously; Pope did not admit authorship until 1735.

Pope reveals in his introductory statement, "The Design," that An Essay on Man was originally conceived as part of a longer philosophical poem, with four separate books. What we have today would comprise the first book. The second was to be a set of epistles on human reason, arts and sciences, human talent, as well as the use of learning, science, and wit "together with a satire against the misapplications of them." The third book would discuss politics, and the fourth book "private ethics" or "practical morality." Often quoted is the following passage, the first verse paragraph of the second book, which neatly summarizes some of the religious and humanistic tenets of the poem:

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan

The proper study of Mankind is Man.

Placed on this isthmus of a middle state,

A Being darkly wise, and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the Sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the Stoic's pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest;

In doubt to deem himself a God, or Beast;

In doubt his mind or body to prefer;

Born but to die, and reas'ning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such,

Whether he thinks too little, or too much;

Chaos of Thought and Passion, all confus'd;

Still by himself, abus'd or disabus'd;

Created half to rise and half to fall;

Great Lord of all things, yet a prey to all,

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurl'd;

The glory, jest and riddle of the world.

Go, wondrous creature! mount where science guides,

Go, measure earth, weigh air, and state the tides;

Instruct the planets in what orbs to run,

Correct old time, and regulate the sun;

Go, soar with Plato to th’ empyreal sphere,

To the first good, first perfect, and first fair;

Or tread the mazy round his followers trod,

And quitting sense call imitating God;

As Eastern priests in giddy circles run,

And turn their heads to imitate the sun.

Go, teach Eternal Wisdom how to rule—

Then drop into thyself, and be a fool!

Pope says that man has learnt about Nature and God's creation by using science; science has given man power but man intoxicated by this power thinks that he is "imitating God". Pope uses the word "fool" to show how little he (man) knows in spite of the progress made by science.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Alexander Pope's Essay on Man: An Introduction

David Cody, Associate Professor of English, Hartwick College

The Essay on Man is a philosophical poem, written, characteristically, in heroic couplets, and published between 1732 and 1734. Pope intended it as the centerpiece of a proposed system of ethics to be put forth in poetic form: it is in fact a fragment of a larger work which Pope planned but did not live to complete. It is an attempt to justify, as Milton had attempted to vindicate, the ways of God to Man, and a warning that man himself is not, as, in his pride, he seems to believe, the center of all things. Though not explicitly Christian, the Essay makes the implicit assumption that man is fallen and unregenerate, and that he must seek his own salvation.

The "Essay" consists of four epistles, addressed to Lord Bolingbroke, and derived, to some extent, from some of Bolingbroke's own fragmentary philosophical writings, as well as from ideas expressed by the deistic third Earl of Shaftsbury. Pope sets out to demonstrate that no matter how imperfect, complex, inscrutable, and disturbingly full of evil the Universe may appear to be, it does function in a rational fashion, according to natural laws; and is, in fact, considered as a whole, a perfect work of God. It appears imperfect to us only because our perceptions are limited by our feeble moral and intellectual capacity. His conclusion is that we must learn to accept our position in the Great Chain of Being — a "middle state," below that of the angels but above that of the beasts — in which we can, at least potentially, lead happy and virtuous lives.

Epistle I concerns itself with the nature of man and with his place in the universe; Epistle II, with man as an individual; Epistle III, with man in relation to human society, to the political and social hierarchies; and Epistle IV, with man's pursuit of happiness in this world. An Essay on Man was a controversial work in Pope's day, praised by some and criticized by others, primarily because it appeared to contemporary critics that its emphasis, in spite of its themes, was primarily poetic and not, strictly speaking, philosophical in any really coherent sense: Dr. Johnson, never one to mince words, and possessed, in any case, of views upon the subject which differed materially from those which Pope had set forth, noted dryly (in what is surely one of the most back-handed literary compliments of all time) that "Never were penury of knowledge and vulgarity of sentiment so happily disguised." It is a subtler work, however, than perhaps Johnson realized: G. Wilson Knight has made the perceptive comment that the poem is not a "static scheme" but a "living organism," (like Twickenham) and that it must be understood as such.

Considered as a whole, the Essay on Man is an affirmative poem of faith: life seems chaotic and patternless to man when he is in the midst of it, but is in fact a coherent portion of a divinely ordered plan. In Pope's world God exists, and he is benificent: his universe is an ordered place. The limited intellect of man can perceive only a tiny portion of this order, and can experience only partial truths, and hence must rely on hope, which leads to faith. Man must be cognizant of his rather insignificant position in the grand scheme of things: those things which he covets most — riches, power, fame — prove to be worthless in the greater context of which he is only dimly aware. In his place, it is man's duty to strive to be good, even if he is doomed, because of his inherent frailty, to fail in his attempt. Do you find Pope's argument convincing? In what ways can we relate the Essay on Man to works like Swift's Gulliver's Travels, Johnson's "The Vanity of Human Wishes" (text), Tennyson's In Memoriam and Eliot's The Wasteland?