The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea,

The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimm'ring landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow'r

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such, as wand'ring near her secret bow'r,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mould'ring heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,

The swallow twitt'ring from the straw-built shed,

The cock's shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed.

For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn,

Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

No children run to lisp their sire's return,

Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share.

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bow'd the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

The short and simple annals of the poor.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Nor you, ye proud, impute to these the fault,

If Mem'ry o'er their tomb no trophies raise,

Where thro' the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault

The pealing anthem swells the note of praise.

Can storied urn or animated bust

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust,

Or Flatt'ry soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire;

Hands, that the rod of empire might have sway'd,

Or wak'd to ecstasy the living lyre.

But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page

Rich with the spoils of time did ne'er unroll;

Chill Penury repress'd their noble rage,

And froze the genial current of the soul.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene,

The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear:

Full many a flow'r is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast

The little tyrant of his fields withstood;

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

Some Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood.

Th' applause of list'ning senates to command,

The threats of pain and ruin to despise,

To scatter plenty o'er a smiling land,

And read their hist'ry in a nation's eyes,

Their lot forbade: nor circumscrib'd alone

Their growing virtues, but their crimes confin'd;

Forbade to wade through slaughter to a throne,

And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,

The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide,

To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame,

Or heap the shrine of Luxury and Pride

With incense kindled at the Muse's flame.

Far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife,

Their sober wishes never learn'd to stray;

Along the cool sequester'd vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenor of their way.

Yet ev'n these bones from insult to protect,

Some frail memorial still erected nigh,

With uncouth rhymes and shapeless sculpture deck'd,

Implores the passing tribute of a sigh.

Their name, their years, spelt by th' unletter'd muse,

The place of fame and elegy supply:

And many a holy text around she strews,

That teach the rustic moralist to die.

For who to dumb Forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing anxious being e'er resign'd,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing, ling'ring look behind?

On some fond breast the parting soul relies,

Some pious drops the closing eye requires;

Ev'n from the tomb the voice of Nature cries,

Ev'n in our ashes live their wonted fires.

For thee, who mindful of th' unhonour'd Dead

Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

If chance, by lonely contemplation led,

Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,

Haply some hoary-headed swain may say,

"Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn

Brushing with hasty steps the dews away

To meet the sun upon the upland lawn.

"There at the foot of yonder nodding beech

That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high,

His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

"Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

Mutt'ring his wayward fancies he would rove,

Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn,

Or craz'd with care, or cross'd in hopeless love.

"One morn I miss'd him on the custom'd hill,

Along the heath and near his fav'rite tree;

Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

"The next with dirges due in sad array

Slow thro' the church-way path we saw him borne.

Approach and read (for thou canst read) the lay,

Grav'd on the stone beneath yon aged thorn."

THE EPITAPH

Here rests his head upon the lap of Earth

A youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown.

Fair Science frown'd not on his humble birth,

And Melancholy mark'd him for her own.

Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

Heav'n did a recompense as largely send:

He gave to Mis'ry all he had, a tear,

He gain'd from Heav'n ('twas all he wish'd) a friend.

No farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode,

(There they alike in trembling hope repose)

The bosom of his Father and his God.

Biographical links

Thomas Gray

Plaque marking Thomas Gray's birthplace at 39 Cornhill, London

Early life and education[edit]

Thomas Gray was born in

Cornhill, London. His father, Philip Gray, was a

scrivener and his mother, Dorothy Antrobus, was a

milliner[1] He was the fifth of 12 children, and the only child of Philip and Dorothy Gray to survive infancy.

[2] He lived with his mother after she left his abusive and mentally unwell father. Gray's mother once saved his life by opening one of his veins with her hands.

[3]

Gray's mother paid for him to go to

Eton College where two of his uncles worked: Robert and William Antrobus. Robert became Gray's first teacher and helped inspire in Gray a love for

botany and

observational science. Gray's other uncle, William, became his tutor.

[4] He recalled his schooldays as a time of great happiness, as is evident in his

Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College. Gray was a delicate and scholarly boy who spent his time reading and avoiding

athletics. He lived in his uncle’s household rather than at college. He made three close friends at Eton:

Horace Walpole, son of the Prime Minister

Robert Walpole; Thomas Ashton, and Richard West, son of another

Richard West who was briefly

Lord Chancellor of Ireland. The four prided themselves on their sense of style, sense of humour, and appreciation of beauty. They were called the "quadruple alliance."

[5]

In 1734 Gray went up to

Peterhouse, Cambridge.

[6] He found the curriculum dull. He wrote letters to friends listing all the things he disliked: the masters ("mad with Pride") and the Fellows ("sleepy, drunken, dull, illiterate Things"). Intended by his family for the law, he spent most of his time as an undergraduate reading classical and modern literature, and playing

Vivaldi and

Scarlatti on the

harpsichord for relaxation.

In 1738 he accompanied his old school-friend Walpole on his

Grand Tour of Europe, possibly at Walpole's expense. The two fell out and parted in

Tuscany, because Walpole wanted to attend fashionable parties and Gray wanted to visit all the

antiquities. They were reconciled a few years later. It was Walpole who later helped publish Gray's poetry. When Gray sent his most famous poem, "Elegy," to Walpole, Walpole sent off the poem as a manuscript and it appeared in different magazines. Gray then published the poem himself and received the credit he was due

[1]

Writing and academia[edit]

Gray began seriously writing poems in 1742, mainly after his close friend Richard West died. He moved to Cambridge and began a self-imposed programme of literary study, becoming one of the most learned men of his time, though he claimed to be lazy by inclination. Gray was a brilliant

bookworm, a quiet, abstracted, dreaming scholar, often afraid of the shadows of his own fame.

[7] He became a

Fellow first of

Peterhouse, and later of

Pembroke College, Cambridge. Gray moved to Pembroke after the students at Peterhouse played a prank on him.

[8]

Gray spent most of his life as a scholar in Cambridge, and only later in his life did he begin traveling again. Although he was one of the least productive poets (his collected works published during his lifetime amount to fewer than 1,000 lines), he is regarded as the foremost English-language poet of the mid-18th century. In 1757, he was offered the post of

Poet Laureate, which he refused. Gray was so self-critical and fearful of failure that he published only thirteen poems during his lifetime. He once wrote that he feared his collected works would be "mistaken for the works of a flea". Walpole said that "He never wrote anything easily but things of Humour."

[9] Gray came to be known as one of the "

Graveyard poets" of the late 18th century, along with

Oliver Goldsmith,

William Cowper, and

Christopher Smart. Gray perhaps knew these men, sharing ideas about death, mortality, and the finality and sublimity of death.

In 1762, the

Regius chair of

Modern History at Cambridge, a

sinecure which carried a salary of £400, fell vacant after the death of

Shallet Turner, and Gray's friends lobbied the government unsuccessfully to secure the position for him. In the event, Gray lost out to

Lawrence Brockett, but he secured the position in 1768 after Brockett's death.

[10]

"Elegy" masterpiece[edit]

It is believed that Gray began writing his masterpiece, the

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, in the graveyard of St Giles parish church in

Stoke Poges,

Buckinghamshire, in 1742. After several years of leaving it unfinished, he completed it in 1750

[11] (see

Elegy for the form). The poem was a literary sensation when published by

Robert Dodsley in February 1751 (see

1751 in poetry). Its reflective, calm and

stoic tone was greatly admired, and it was pirated, imitated, quoted and translated into Latin and Greek; it is still one of the most popular and most frequently quoted poems in the English language.

[12] In 1759 during the

Seven Years War, before the

Battle of the Plains of Abraham, British General

James Wolfe is said to have recited it to his officers, adding: "Gentlemen, I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec tomorrow".

The

Elegy was recognised immediately for its beauty and skill.

[citation needed] It contains many phrases which have entered the common English lexicon, either on their own or as quoted in other works.

[citation needed] These include:

- "The Paths of Glory"

- "Celestial fire"

- "Some mute inglorious Milton"

- "Far from the Madding Crowd"

- "The unlettered muse"

- "Kindred spirit"

"Elegy" contemplates such themes as death and afterlife. These themes foreshadowed the upcoming Gothic movement. It is suggested that perhaps Gray found inspiration for his poem by visiting the gravesite of his aunt, Mary Antrobus. The aunt was buried at the graveyard by the St. Giles' churchyard, which he and his mother would visit. This is the same gravesite where Gray himself was later buried.

[13]

Gray also wrote light verse, including

Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat, Drowned in a Tub of Gold Fishes, a mock elegy concerning

Horace Walpole's cat. After setting the scene with the couplet "What female heart can gold despise? What cat's averse to fish?", the poem moves to its multiple proverbial conclusion: "a fav'rite has no friend", "[k]now one false step is ne'er retrieved" and "nor all that glisters, gold". (Walpole later displayed the fatal china vase (the tub) on a pedestal at his house in

Strawberry Hill.)

Gray’s surviving letters also show his sharp observation and playful sense of humour. He is well known for his phrase, "where

ignorance is bliss, 'tis folly to be wise." The phrase, from

Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College, is possibly one of the most misconstrued phrases in English literature. Gray is not promoting ignorance, but is reflecting with nostalgia on a time when he was allowed to be ignorant, his youth (

1742). It has been asserted that the Ode also abounds with images which find "a mirror in every mind".

[14] This was stated by Samuel Johnson who said of the poem, "I rejoice to concur with the common reader ... The Church-yard abounds with images which find a mirror in every mind, and with sentiments to which every bosom returns an echo".

[1] Indeed, Gray's poem follows the style of the mid-century literary endeavor to write of "universal feelings."

[15] Samuel Johnson also said of Gray that he spoke in "two languages". He spoke in the language of "public" and "private" and according to Johnson, he should have spoken more in his private language as he did in his "Elegy" poem.

[16]

Forms

The Hours by

Maria Cosway, an illustration to Gray's poem

Ode on the Spring, referring to the lines "Lo! where the rosy-bosomed Hours, Fair Venus' train, appear"

Gray considered his two

Pindaric odes,

The Progress of Poesy and

The Bard, as his best works. Pindaric odes are to be written with fire and passion, unlike the calmer and more reflective Horatian odes such as

Ode on a distant Prospect of Eton College.

The Bard tells of a wild Welsh poet cursing the Norman king

Edward I after his conquest of Wales and prophesying in detail the downfall of the

House of Plantagenet. It is melodramatic, and ends with the bard hurling himself to his death from the top of a mountain.

When his duties allowed, Gray travelled widely throughout Britain to places such as Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Scotland in search of

picturesque landscapes and ancient monuments. These elements were not generally valued in the early 18th century, when the popular taste ran to

classical styles in architecture and literature, and most people liked their scenery tame and well-tended. Some

[who?] have seen Gray’s writings on this topic, and the

Gothic details that appear in his

Elegy and

The Bard as the first foreshadowing of the

Romantic movement that dominated the early 19th century, when

William Wordsworth and the other

Lake poets taught people to value the picturesque, the sublime, and the Gothic.

[citation needed] Gray combined traditional forms and poetic diction with new topics and modes of expression, and may be considered as a classically focused precursor of the

romantic revival.

[citation needed]

Gray's connection to the

Romantic poets is vexed. In the prefaces to the 1800 and 1802 editions of Wordsworth's and

Samuel Taylor Coleridge's

Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth singled out Gray's "Sonnet on the Death of Richard West" to exemplify what he found most objectionable in poetry, declaring it was

"Gray, who was at the head of those who, by their reasonings, have attempted to widen the space of separation betwixt prose and metrical composition, and was more than any other man curiously elaborate in the structure of his own poetic diction."

[17]

Gray wrote in a letter to West, that "the language of the age is never the language of poetry."

[17]

Death

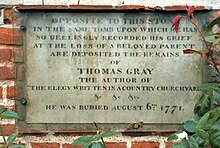

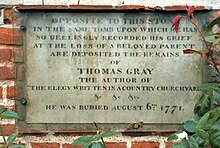

Tomb of Thomas Gray in Stoke Poges Churchyard

Gray died on 30 July 1771 in Cambridge, and was buried beside his mother in the churchyard of

Stoke Poges, the setting for his famous

Elegy. His grave can still be seen there.

Honours