Christopher Tolkien

Christopher Tolkien | |

|---|---|

Tolkien in 2019 | |

| Born | Christopher John Reuel Tolkien 21 November 1924 Leeds, England |

| Died | 16 January 2020 (aged 95) Draguignan, France |

| Occupation | Editor, illustrator, academic |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford (B.A., B.Litt.) |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Notable awards | Bodley Medal (2016) |

| Spouse | Faith Faulconbridge Baillie Klass |

| Children | 3, including Simon Tolkien |

| Parents | J. R. R. Tolkien Edith Tolkien |

| Relatives | John Francis Reuel Tolkien (brother) |

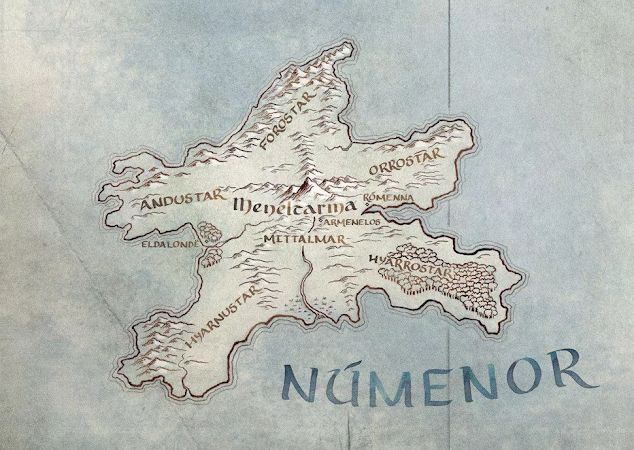

Christopher John Reuel Tolkien (21 November 1924 – 16 January 2020) was an English and French academic editor. He was the son of author J. R. R. Tolkien and the editor of much of his father's posthumously published work. Tolkien drew the original maps for his father's The Lord of the Rings.

Early life

Tolkien was born in Leeds, England, the third of four children and youngest son of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and his wife, Edith Mary Tolkien (née Bratt). He was educated at the Dragon School (Oxford) and later at The Oratory School.[1]

He entered the Royal Air Force in mid-1943 and was sent to South Africa for flight training, completing the elementary flying course at 7 Air School, Kroonstad, and the service flying course at 25 Air School, Standerton. He was commissioned into the general duties branch of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve on 27 January 1945 as a pilot officer on probation (emergency) and was given the service number 193121.[2] He briefly served as an RAF pilot before transferring to the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve on 28 June 1945.[3] His commission was confirmed and it was announced he was promoted to flying officer (war substantive) on 27 July 1945.[4][5]

After the war, he studied English at Trinity College, Oxford, taking his B.A. in 1949 and his B.Litt. a few years later.[6]

Career

Tolkien had long been part of the critical audience for his father's fiction, first as a child listening to tales of Bilbo Baggins (which were published as The Hobbit), and then as a teenager and young adult offering much feedback on The Lord of the Rings during its 15-year gestation. He had the task of interpreting his father's sometimes self-contradictory maps of Middle-earth in order to produce the versions used in the books, and he re-drew the main map in the late 1970s to clarify the lettering and correct some errors and omissions. Tolkien was invited by his father to join the Inklings when he was 21 years old, making him the youngest member of the informal literary discussion society that included C. S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, Warren Lewis, Lord David Cecil, and Nevill Coghill.[7]

He published The Saga of King Heidrek the Wise: "Translated from the Icelandic with Introduction, Notes and Appendices by Christopher Tolkien" in 1960.[8] Later, Tolkien followed in his father's footsteps, becoming a lecturer and tutor in English Language at New College, Oxford, from 1964 to 1975.[6]

In 2016, he was given the Bodley Medal, an award that recognises outstanding contributions to literature, culture, science, and communication.[9]

Editorial work

His father wrote a great deal of material connected to the Middle-earth legendarium that was not published in his lifetime. He had originally intended to publish The Silmarillion along with The Lord of the Rings, and parts of it were in a finished state when he died in 1973, but the project was incomplete. Tolkien once referred to his son as his "chief critic and collaborator", and named him his literary executor in his will. Tolkien organised the masses of his father's unpublished writings, some of them written on odd scraps of paper a half-century earlier. Much of the material was handwritten; frequently a fair draft was written over a half-erased first draft, and names of characters routinely changed between the beginning and end of the same draft. In the years following, Tolkien worked on the manuscripts and was able to produce an edition of The Silmarillion for publication in 1977.[10]

The Silmarillion was followed by Unfinished Tales in 1980, and The History of Middle-earth in 12 volumes between 1983 and 1996. Most of the original source-texts have been made public from which The Silmarillion was constructed. In April 2007, Tolkien published The Children of Húrin, whose story his father had brought to a relatively complete stage between 1951 and 1957 before abandoning it. This was one of his father's earliest stories, its first version dating back to 1918; several versions are published in The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and The History of Middle-earth. The Children of Húrin is a synthesis of these and other sources. Beren and Lúthien is an editorial work and was published as a stand-alone book in 2017.[11]

The next year, The Fall of Gondolin was published, also as an editorial work.[12] The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and The Fall of Gondolin make up the three "Great Tales" of the Elder Days which J.R.R. Tolkien considered to be the biggest stories of the First Age.[13]

HarperCollins published other J. R. R. Tolkien work edited by Tolkien which is not connected to the Middle-earth legendarium. The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún appeared in May 2009, a verse retelling of the Norse Völsung cycle, followed by The Fall of Arthur[14] in May 2013, and by Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary in May 2014.[15][16]

Tolkien served as chairman of the Tolkien Estate, Ltd., the entity formed to handle the business side of his father's literary legacy, and as a trustee of the Tolkien Charitable Trust. He resigned as director of the estate in 2017.[17]

Reaction to filmed versions

In 2001, he expressed doubts over The Lord of the Rings film trilogy directed by Peter Jackson, questioning the viability of a film interpretation that retained the essence of the work, but stressed that this was just his opinion.[18] In a 2012 interview with Le Monde he criticised the films saying: "They gutted the book, making an action film for 15 to 25-year-olds."[19]

In 2008, Tolkien commenced legal proceedings against New Line Cinema, which he claimed owed his family £80 million in unpaid royalties.[20] In September 2009, he and New Line reached an undisclosed settlement, and he withdrew his legal objection to The Hobbit films.[21]

Personal life

Tolkien lived from 1975 in the French countryside with his second wife, Baillie Tolkien (née Klass), who edited his father's The Father Christmas Letters for posthumous publication. They had two children, Adam Reuel Tolkien and Rachel Clare Reuel Tolkien. In the wake of a dispute surrounding the making of The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, he disowned his son by his first marriage, barrister and novelist Simon Mario Reuel Tolkien,[22] though they reconciled prior to Christopher's death.[23]

He died on 16 January 2020, at the age of 95, in Draguignan, Var, France.[10][24][25][26]

Bibliography

As author or translator

- Tolkien, Christopher (1953–1957). The Battle of the Goths and the Huns (PDF). Saga-Book. 14. pp. 141–63.

- The Saga of King Heidrek the Wise (PDF). Translated by ———. 1960., from the Icelandic Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks

As editor

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (1958) [1387–1400]. ———; Coghill, Nevill (eds.). The Nun's Priest's Tale.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (1959) [1387–1400]. ———; Coghill, Nevill (eds.). The Pardoner's Tale.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (1969) [1387–1400]. ———; Coghill, Nevill (eds.). The Man of Law's Tale.

- ———, ed. (1975). Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. Translated by Tolkien, J. R. R.; Gordon, E.V.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). ——— (ed.). The Silmarillion. ISBN 9780395257302.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1979). ——— (ed.). Pictures by J. R. R. Tolkien. ISBN 9780047410031.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2010) [1980]. ——— (ed.). Unfinished Tales. ISBN 978-0261102163.

- Carpenter, Humphrey; ———, eds. (2005) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. ISBN 978-0261102651.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2007) [1983]. ——— (ed.). The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays. ISBN 978-0261102637.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983–2002). ——— (ed.). The History of Middle-earth. ISBN 978-0008259846.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983). ——— (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. 1. ISBN 978-0261102224.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984). ——— (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales, part 2. 2. ISBN 978-0261102149.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1985). ——— (ed.). The Lays of Beleriand. 3. ISBN 978-0261102262.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1986). ——— (ed.). The Shaping of Middle-earth. 4. ISBN 9780261102187.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). ——— (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. 5. ISBN 9780007348220.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988). ——— (ed.). The Return of the Shadow. 6. ISBN 9780007365302.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1989). ——— (ed.). The Treason of Isengard. 7. ISBN 978-0395515624.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1990). ——— (ed.). The War of the Ring. 8. ISBN 978-0261102231.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1992). ——— (ed.). Sauron Defeated. 9. ISBN 978-0395606490.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1993). ——— (ed.). Morgoth's Ring. 10. ISBN 978-0261103009.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). ——— (ed.). The War of the Jewels. 11. ISBN 978-0261103245.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). ——— (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. 12. ISBN 978-0261103481.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2002). ——— (ed.). The History of Middle-earth Index.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2007). ——— (ed.). The Children of Húrin. ISBN 978-0007597338.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2009). ——— (ed.). The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún. ISBN 978-0007317240.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2013). ——— (ed.). The Fall of Arthur. ISBN 978-0007557301.

- ———, ed. (2014). Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary. Translated by Tolkien, J. R. R. ISBN 978-0007590094.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2017). ——— (ed.). Beren and Lúthien. ISBN 978-0008214197.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2018). ——— (ed.). The Fall of Gondolin. ISBN 978-0008302757.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). ——— (ed.). The Silmarillion. ISBN 9780395257302.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1979). ——— (ed.). Pictures by J. R. R. Tolkien. ISBN 9780047410031.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2010) [1980]. ——— (ed.). Unfinished Tales. ISBN 978-0261102163.

Carpenter, Humphrey; ———, eds. (2005) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. ISBN 978-0261102651.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2007) [1983]. ——— (ed.). The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays. ISBN 978-0261102637.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983–2002). ——— (ed.). The History of Middle-earth. ISBN 978-0008259846.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983). ——— (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. 1. ISBN 978-0261102224.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984). ——— (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales, part 2. 2. ISBN 978-0261102149.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1985). ——— (ed.). The Lays of Beleriand. 3. ISBN 978-0261102262.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1986). ——— (ed.). The Shaping of Middle-earth. 4. ISBN 9780261102187.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). ——— (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. 5. ISBN 9780007348220.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988). ——— (ed.). The Return of the Shadow. 6. ISBN 9780007365302.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1989). ——— (ed.). The Treason of Isengard. 7. ISBN 978-0395515624.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1990). ——— (ed.). The War of the Ring. 8. ISBN 978-0261102231.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1992). ——— (ed.). Sauron Defeated. 9. ISBN 978-0395606490.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1993). ——— (ed.). Morgoth's Ring. 10. ISBN 978-0261103009.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). ——— (ed.). The War of the Jewels. 11. ISBN 978-0261103245.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). ——— (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. 12. ISBN 978-0261103481.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2002). ——— (ed.). The History of Middle-earth Index.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2007). ——— (ed.). The Children of Húrin. ISBN 978-0007597338.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2009). ——— (ed.). The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún. ISBN 978-0007317240.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2017). ——— (ed.). Beren and Lúthien. ISBN 978-0008214197.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2018). ——— (ed.). The Fall of Gondolin. ISBN 978-0008302757.

* * * * * * * *

Other References for Reading Order

* * * * * * * *

Key

Silm: Silmarillion

UT: Unfinished Tales

LotR: Lord of the Rings

Lays: The Lays of Beleriand (History of Middle-earth 3)

Shaping: The Shaping of Middle-earth (History of Middle-earth 4)

Lost Road: The Lost Road and Other Writings (History of Middle-earth 5)

Sauron: Sauron Defeated (History of Middle-earth 9)

Morg Ring: Morgoth's Ring (History of Middle-earth 10)

War Jewel: War of the Jewels (History of Middle-earth 11)

People: The Peoples of Middle-earth (History of Middle-earth 12)

Zeroth Age

Silmarillion: Ainulindale.

Silm: Valaquenta

First Age

Quenta Silmarillion, etc

Silm: Chap 1

Shaping: Ambarkanta

Silm: Chap 2-3

People: Chap 13 Cirdan

War Jewel: Part 3, Chap 4

Lost Road: Part 2, Chap 5

Morg Ring: Part 2, Sect 2, Finwe and Miriel, etc, pp 205-271

Silm: Chap 4-6

People: Chap 11

Silm: Chap 7-9

Lays Bel: Part 2(i)

Silm: Chap 10-11

Lost Tales 1: Chap 8

Silm: Chap 12-15

Morg Ring: Part 4

Silm: Chap 16-19

People: Chap 10

Silm: Chap 17-19

Lays Bel: Part 3-4

Silm: Chap 20-21

War Jewel: Part 3, Chap 2

UT: Part 1, Chap 2

The Children of Hurin

Lays Bel: Part 1

War Jewel: Part 3, Chap 1

Silm: Chap 22-23

War Jewel: Part 3, Chap 3

UT: Part 1, Chap 1

Lost Tales 2: Chap 3

Lays: Part 2(iii)

Shaping: The Horns of Ylmir

Lays Bel: 2(ii)

Silm: Chap 24

Second Age

UT: Part 4, Chap 1, Chap 3

UT: Part 2

People: Chap 13 Glorfindel

People: Chap 17

Silm: Of the Rings of Power

Akallabeth

Silm: Akallabeth

Lost Road: Part 1

Sauron: Part 2-3

Third Age

UT: Part 3, Chap 1

UT: Part 4, Chap 2

People: Chap 13 Istari

UT: Part 3, Chap 2

There and Back Again

Hobbit

UT: Part 3, chap 3

War of the Rings

LotR: FotR

UT: Part 3, Chap 4-5

People: Chap 15

LotR: TT

LotR: RotK

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

Fourth Age

People: Chap 16

* * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * *

Suggested Reading Order

1. The Hobbit (1937)2. The Fellowship of the Ring (1954)

3. The Two Towers (1954)

4. The Return of the King (1955)

5. The Adventures of Tom Bombadil (1962)

6. The Silmarillion (1977)

7. The Children of Húrin (2007)

8. Any other Middle-earth stories attributed to J.R.R. Tolkien & Christopher Tolkien.

- The Hobbit

- The Lord of the Rings

- The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book

- The Silmarillion

- Unfinished Tales

- The History of Middle-earth series

- The Children of Húrin

- The Legend of Sigurd & Gudrun

- Beren and Lúthien

- The Fall of Gondolin

- The Book of Lost Tales [volumes 1 & 2]

- The Lays of Beleriand

- The Shaping of Middle-earth

- The Lost Road

- The Hobbit

- The Return of the Shadow

- The Treason of Isengard

- The War of the Ring

- Sauron Defeated [first part]

- The Peoples of Middle-earth [first part]

- [The Lord of the Rings]

- The Notion Club Papers [in Sauron Defeated]

- Unfinished Tales [omit Narn i Hîn Húrin]

- The Children of Húrin

- The Legend of Sigurd & Gudrun

- Beren and Lúthien

- The Fall of Gondolin

- Morgoth’s Ring

- The War of the Jewels

- [The Silmarillion]

- The Peoples of Middle-earth [last part]

* * * * * * * *

J. R. R. Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien | |

|---|---|

Tolkien in the 1940s | |

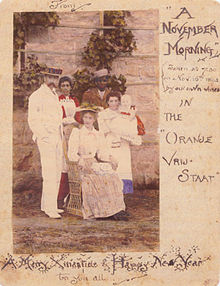

| Born | John Ronald Reuel Tolkien 3 January 1892 Bloemfontein, Orange Free State (modern-day South Africa) |

| Died | 2 September 1973 (aged 81) Bournemouth, England |

| Occupation | Author, academic, philologist, poet |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Exeter College, Oxford |

| Genre | Fantasy, high fantasy, mythopoeia, translation, literary criticism |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Signature |  |

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien CBE FRSL (/ruːl ˈtɒlkiːn/;[a] 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer, poet, philologist, and academic. He was the author of the high fantasy works The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

He served as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon and Fellow of Pembroke College, Oxford, from 1925 to 1945 and Merton Professor of English Language and Literature and Fellow of Merton College, Oxford, from 1945 to 1959.[3] He was at one time a close friend of C. S. Lewis—they were both members of the informal literary discussion group known as the Inklings. Tolkien was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II on 28 March 1972.

After Tolkien's death, his son Christopher published a series of works based on his father's extensive notes and unpublished manuscripts, including The Silmarillion. These, together with The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, form a connected body of tales, poems, fictional histories, invented languages, and literary essays about a fantasy world called Arda and Middle-earth[b] within it. Between 1951 and 1955, Tolkien applied the term legendarium to the larger part of these writings.[4]

While many other authors had published works of fantasy before Tolkien,[5] the great success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings led directly to a popular resurgence of the genre. This has caused Tolkien to be popularly identified as the "father" of modern fantasy literature[6][7]—or, more precisely, of high fantasy.[8] In 2008, The Times ranked him sixth on a list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[9] Forbes ranked him the fifth top-earning "dead celebrity" in 2009.[10]

Biography

Ancestry

Tolkien's immediate paternal ancestors were middle-class craftsmen who made and sold clocks, watches and pianos in London and Birmingham. The Tolkien family originated in the East Prussian town Kreuzburg near Königsberg, which was founded during medieval German eastward expansion, where his earliest-known paternal ancestor Michel Tolkien was born around 1620. Michel's son Christianus Tolkien (1663–1746) was a wealthy miller in Kreuzburg. His son Christian Tolkien (1706–1791) moved from Kreuzburg to nearby Danzig, and his two sons Daniel Gottlieb Tolkien (1747–1813) and Johann (later known as John) Benjamin Tolkien (1752–1819) emigrated to London in the 1770s and became the ancestors of the English family; the younger brother was J. R. R. Tolkien's second great-grandfather. In 1792 John Benjamin Tolkien and William Gravell took over the Erdley Norton manufacture in London, which from then on sold clocks and watches under the name Gravell & Tolkien. Daniel Gottlieb obtained British citizenship in 1794, but John Benjamin apparently never became a British citizen. Other German relatives also joined the two brothers in London. Several people with the surname Tolkien or similar spelling, some of them members of the same family as J. R. R. Tolkien, live in northern Germany, but most of them are descendants of people who evacuated East Prussia in 1945, at the end of World War II.[11][12][13][14]

According to Ryszard Derdziński the Tolkien name is of Low Prussian origin and probably means "son/descendant of Tolk."[11][12] Tolkien mistakenly believed his surname derived from the German word tollkühn, meaning "foolhardy",[15] and jokingly inserted himself as a "cameo" into The Notion Club Papers under the literally translated name Rashbold.[16] However, Derdziński has demonstrated this to be a false etymology.[11][12] While J. R. R. Tolkien was aware of the Tolkien family's German origin, his knowledge of the family's history was limited because he was "early isolated from the family of his prematurely deceased father".[11][12]

Childhood

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born on 3 January 1892 in Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State (later annexed by the British Empire; now Free State Province in the Republic of South Africa), to Arthur Reuel Tolkien (1857–1896), an English bank manager, and his wife Mabel, née Suffield (1870–1904). The couple had left England when Arthur was promoted to head the Bloemfontein office of the British bank for which he worked. Tolkien had one sibling, his younger brother, Hilary Arthur Reuel Tolkien, who was born on 17 February 1894.[17]

As a child, Tolkien was bitten by a large baboon spider in the garden, an event some think later echoed in his stories, although he admitted no actual memory of the event and no special hatred of spiders as an adult. In another incident, a young family servant, who thought Tolkien a beautiful child, took the baby to his kraal to show him off, returning him the next morning.[18]

When he was three, he went to England with his mother and brother on what was intended to be a lengthy family visit. His father, however, died in South Africa of rheumatic fever before he could join them.[19] This left the family without an income, so Tolkien's mother took him to live with her parents in Kings Heath,[20] Birmingham. Soon after, in 1896, they moved to Sarehole (now in Hall Green), then a Worcestershire village, later annexed to Birmingham.[21] He enjoyed exploring Sarehole Mill and Moseley Bog and the Clent, Lickey and Malvern Hills, which would later inspire scenes in his books, along with nearby towns and villages such as Bromsgrove, Alcester, and Alvechurch and places such as his aunt Jane's farm Bag End, the name of which he used in his fiction.[22]

Mabel Tolkien taught her two children at home. Ronald, as he was known in the family, was a keen pupil.[23] She taught him a great deal of botany and awakened in him the enjoyment of the look and feel of plants. Young Tolkien liked to draw landscapes and trees, but his favourite lessons were those concerning languages, and his mother taught him the rudiments of Latin very early.[24]

Tolkien could read by the age of four and could write fluently soon afterwards. His mother allowed him to read many books. He disliked Treasure Island and The Pied Piper and thought Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll was "amusing but disturbing". He liked stories about "Red Indians" (Native Americans) and the fantasy works by George MacDonald.[25] In addition, the "Fairy Books" of Andrew Lang were particularly important to him and their influence is apparent in some of his later writings.[26]

Mabel Tolkien was received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1900 despite vehement protests by her Baptist family,[28] which stopped all financial assistance to her. In 1904, when J. R. R. Tolkien was 12, his mother died of acute diabetes at Fern Cottage in Rednal, which she was renting. She was then about 34 years of age, about as old as a person with diabetes mellitus type 1 could survive without treatment—insulin would not be discovered until two decades later. Nine years after her death, Tolkien wrote, "My own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants so easy a way to his great gifts as he did to Hilary and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labour and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith."[28]

Before her death, Mabel Tolkien had assigned the guardianship of her sons to her close friend, Father Francis Xavier Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory, who was assigned to bring them up as good Catholics. In a 1965 letter to his son Michael, Tolkien recalled the influence of the man whom he always called "Father Francis": "He was an upper-class Welsh-Spaniard Tory, and seemed to some just a pottering old gossip. He was—and he was not. I first learned charity and forgiveness from him; and in the light of it pierced even the 'liberal' darkness out of which I came, knowing more [i.e. Tolkien having grown up knowing more] about 'Bloody Mary' than the Mother of Jesus—who was never mentioned except as an object of wicked worship by the Romanists."[29]

After his mother's death, Tolkien grew up in the Edgbaston area of Birmingham and attended King Edward's School, Birmingham, and later St. Philip's School. In 1903, he won a Foundation Scholarship and returned to King Edward's. While a pupil there, Tolkien was one of the cadets from the school's Officers Training Corps who helped line the route for the 1910 coronation parade of King George V. Like the other cadets from King Edward's, Tolkien was posted just outside the gates of Buckingham Palace.[30]

In Edgbaston, Tolkien lived there in the shadow of Perrott's Folly and the Victorian tower of Edgbaston Waterworks, which may have influenced the images of the dark towers within his works.[31][32] Another strong influence was the romantic medievalist paintings of Edward Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery had a large collection of works on public display.[33]

Youth

While in his early teens, Tolkien had his first encounter with a constructed language, Animalic, an invention of his cousins, Mary and Marjorie Incledon. At that time, he was studying Latin and Anglo-Saxon. Their interest in Animalic soon died away, but Mary and others, including Tolkien himself, invented a new and more complex language called Nevbosh. The next constructed language he came to work with, Naffarin, would be his own creation.[34][35]

Tolkien learned Esperanto some time before 1909. Around 10 June 1909 he composed "The Book of the Foxrook", a sixteen-page notebook, where the "earliest example of one of his invented alphabets" appears.[36] Short texts in this notebook are written in Esperanto.[37]

In 1911, while they were at King Edward's School, Tolkien and three friends, Rob Gilson, Geoffrey Bache Smith and Christopher Wiseman, formed a semi-secret society they called the T.C.B.S. The initials stood for Tea Club and Barrovian Society, alluding to their fondness for drinking tea in Barrow's Stores near the school and, secretly, in the school library.[38][39] After leaving school, the members stayed in touch and, in December 1914, they held a "council" in London at Wiseman's home. For Tolkien, the result of this meeting was a strong dedication to writing poetry.

In 1911, Tolkien went on a summer holiday in Switzerland, a trip that he recollects vividly in a 1968 letter,[30] noting that Bilbo's journey across the Misty Mountains ("including the glissade down the slithering stones into the pine woods") is directly based on his adventures as their party of 12 hiked from Interlaken to Lauterbrunnen and on to camp in the moraines beyond Mürren. Fifty-seven years later, Tolkien remembered his regret at leaving the view of the eternal snows of Jungfrau and Silberhorn, "the Silvertine (Celebdil) of my dreams". They went across the Kleine Scheidegg to Grindelwald and on across the Grosse Scheidegg to Meiringen. They continued across the Grimsel Pass, through the upper Valais to Brig and on to the Aletsch glacier and Zermatt.[40]

In October of the same year, Tolkien began studying at Exeter College, Oxford. He initially studied classics but changed his course in 1913 to English language and literature, graduating in 1915 with first-class honours.[41] Among his tutors at Oxford was Joseph Wright.

Courtship and marriage

At the age of 16, Tolkien met Edith Mary Bratt, who was three years his senior, when he and his brother Hilary moved into the boarding house where she lived in Duchess Road, Edgbaston. According to Humphrey Carpenter, "Edith and Ronald took to frequenting Birmingham teashops, especially one which had a balcony overlooking the pavement. There they would sit and throw sugarlumps into the hats of passers-by, moving to the next table when the sugar bowl was empty. ... With two people of their personalities and in their position, romance was bound to flourish. Both were orphans in need of affection, and they found that they could give it to each other. During the summer of 1909, they decided that they were in love."[42]

His guardian, Father Morgan, viewed Edith as the reason for Tolkien's having "muffed" his exams and considered it "altogether unfortunate"[43] that his surrogate son was romantically involved with an older, Protestant woman. He prohibited him from meeting, talking to, or even corresponding with her until he was 21. He obeyed this prohibition to the letter,[44] with one notable early exception, over which Father Morgan threatened to cut short his university career if he did not stop.[45]

On the evening of his 21st birthday, Tolkien wrote to Edith, who was living with family friend C. H. Jessop at Cheltenham. He declared that he had never ceased to love her, and asked her to marry him. Edith replied that she had already accepted the proposal of George Field, the brother of one of her closest school friends. But Edith said she had agreed to marry Field only because she felt "on the shelf" and had begun to doubt that Tolkien still cared for her. She explained that, because of Tolkien's letter, everything had changed.

On 8 January 1913, Tolkien travelled by train to Cheltenham and was met on the platform by Edith. The two took a walk into the countryside, sat under a railway viaduct, and talked. By the end of the day, Edith had agreed to accept Tolkien's proposal. She wrote to Field and returned her engagement ring. Field was "dreadfully upset at first", and the Field family was "insulted and angry".[46] Upon learning of Edith's new plans, Jessop wrote to her guardian, "I have nothing to say against Tolkien, he is a cultured gentleman, but his prospects are poor in the extreme, and when he will be in a position to marry I cannot imagine. Had he adopted a profession it would have been different."[47]

Following their engagement, Edith reluctantly announced that she was converting to Catholicism at Tolkien's insistence. Jessop, "like many others of his age and class ... strongly anti-Catholic", was infuriated, and he ordered Edith to find other lodgings.[48]

Edith Bratt and Ronald Tolkien were formally engaged at Birmingham in January 1913, and married at St. Mary Immaculate Roman Catholic Church, Warwick, on 22 March 1916.[49] In his 1941 letter to Michael, Tolkien expressed admiration for his wife's willingness to marry a man with no job, little money, and no prospects except the likelihood of being killed in the Great War.[43]

First World War

J. R. R. Tolkien | |

|---|---|

| |

| Branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1915–1920 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit | Lancashire Fusiliers |

| Battles | |

In August 1914, Britain entered the First World War. Tolkien's relatives were shocked when he elected not to volunteer immediately for the British Army. In a 1941 letter to his son Michael, Tolkien recalled: "In those days chaps joined up, or were scorned publicly. It was a nasty cleft to be in for a young man with too much imagination and little physical courage."[43]

Instead, Tolkien, "endured the obloquy",[43] and entered a programme by which he delayed enlistment until completing his degree. By the time he passed his finals in July 1915, Tolkien recalled that the hints were "becoming outspoken from relatives".[43] He was commissioned as a temporary second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers on 15 July 1915.[50][51] He trained with the 13th (Reserve) Battalion on Cannock Chase, Staffordshire, for 11 months. In a letter to Edith, Tolkien complained: "Gentlemen are rare among the superiors, and even human beings rare indeed."[52] Following their wedding, Lieutenant and Mrs. Tolkien took up lodgings near the training camp.

On 2 June 1916, Tolkien received a telegram summoning him to Folkestone for posting to France. The Tolkiens spent the night before his departure in a room at the Plough & Harrow Hotel in Edgbaston, Birmingham.

He later wrote: "Junior officers were being killed off, a dozen a minute. Parting from my wife then ... it was like a death."[53]

France

On 5 June 1916, Tolkien boarded a troop transport for an overnight voyage to Calais. Like other soldiers arriving for the first time, he was sent to the British Expeditionary Force's (BEF) base depot at Étaples. On 7 June, he was informed that he had been assigned as a signals officer to the 11th (Service) Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers. The battalion was part of the 74th Brigade, 25th Division.

While waiting to be summoned to his unit, Tolkien sank into boredom. To pass the time, he composed a poem entitled The Lonely Isle, which was inspired by his feelings during the sea crossing to Calais. To evade the British Army's postal censorship, he also developed a code of dots by which Edith could track his movements.[54]

He left Étaples on 27 June 1916 and joined his battalion at Rubempré, near Amiens.[55] He found himself commanding enlisted men who were drawn mainly from the mining, milling, and weaving towns of Lancashire.[56] According to John Garth, he "felt an affinity for these working class men", but military protocol prohibited friendships with "other ranks". Instead, he was required to "take charge of them, discipline them, train them, and probably censor their letters ... If possible, he was supposed to inspire their love and loyalty."[57]

Tolkien later lamented, "The most improper job of any man ... is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity."[57]

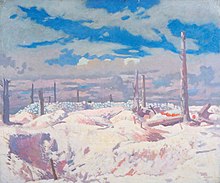

Battle of the Somme

Tolkien arrived at the Somme in early July 1916. In between terms behind the lines at Bouzincourt, he participated in the assaults on the Schwaben Redoubt and the Leipzig salient. Tolkien's time in combat was a terrible stress for Edith, who feared that every knock on the door might carry news of her husband's death. Edith could track her husband's movements on a map of the Western Front. The Reverend Mervyn S. Evers, Anglican chaplain to the Lancashire Fusiliers, recorded that Tolkien and his brother officers were eaten by "hordes of lice" which found the Medical Officer's ointment merely "a kind of hors d'oeuvre and the little beggars went at their feast with renewed vigour."[58]

On 27 October 1916, as his battalion attacked Regina Trench, Tolkien contracted trench fever, a disease carried by the lice. He was invalided to England on 8 November 1916.[59] Many of his dearest school friends were killed in the war. Among their number were Rob Gilson of the Tea Club and Barrovian Society, who was killed on the first day of the Somme while leading his men in the assault on Beaumont Hamel. Fellow T.C.B.S. member Geoffrey Smith was killed during the same battle when a German artillery shell landed on a first-aid post. Tolkien's battalion was almost completely wiped out following his return to England.[60]

According to John Garth, Kitchener's army at once marked existing social boundaries and counteracted the class system by throwing everyone into a desperate situation together. Tolkien was grateful, writing that it had taught him, "a deep sympathy and feeling for the Tommy; especially the plain soldier from the agricultural counties".[61]

Home front

A weak and emaciated Tolkien spent the remainder of the war alternating between hospitals and garrison duties, being deemed medically unfit for general service.[62][63][64]

During his recovery in a cottage in Little Haywood, Staffordshire, he began to work on what he called The Book of Lost Tales, beginning with The Fall of Gondolin. Lost Tales represented Tolkien's attempt to create a mythology for England, a project he would abandon without ever completing.[65] Throughout 1917 and 1918 his illness kept recurring, but he had recovered enough to do home service at various camps. It was at this time that Edith bore their first child, John Francis Reuel Tolkien. In a 1941 letter, Tolkien described his son John as "(conceived and carried during the starvation-year of 1917 and the great U-Boat campaign) round about the Battle of Cambrai, when the end of the war seemed as far off as it does now".[43]

Tolkien was promoted to the temporary rank of lieutenant on 6 January 1918.[66] When he was stationed at Kingston upon Hull, he and Edith went walking in the woods at nearby Roos, and Edith began to dance for him in a clearing among the flowering hemlock. After his wife's death in 1971, Tolkien remembered,

On 16 July 1919 Tolkien was officially demobilized, at Fovant, on Salisbury Plain, with a temporary disability pension.[69]

Academic and writing career

On 3 November 1920, Tolkien was demobilized and left the army, retaining his rank of lieutenant.[70] His first civilian job after World War I was at the Oxford English Dictionary, where he worked mainly on the history and etymology of words of Germanic origin beginning with the letter W.[71] In 1920, he took up a post as reader in English language at the University of Leeds, becoming the youngest professor there.[72] While at Leeds, he produced A Middle English Vocabulary and a definitive edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight with E. V. Gordon; both became academic standard works for several decades. He translated Sir Gawain, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. In 1925, he returned to Oxford as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, with a fellowship at Pembroke College.

In mid-1919, he began to tutor undergraduates privately, most importantly those of Lady Margaret Hall and St Hugh's College, given that the women's colleges were in great need of good teachers in their early years, and Tolkien as a married professor (then still not common) was considered suitable, as a bachelor don would not have been.[73]

During his time at Pembroke College Tolkien wrote The Hobbit and the first two volumes of The Lord of the Rings, while living at 20 Northmoor Road in North Oxford (where a blue plaque was placed in 2002). He also published a philological essay in 1932 on the name "Nodens", following Sir Mortimer Wheeler's unearthing of a Roman Asclepeion at Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, in 1928.[74]

Beowulf

In the 1920s, Tolkien undertook a translation of Beowulf, which he finished in 1926, but did not publish. It was finally edited by his son and published in 2014, more than 40 years after Tolkien's death and almost 90 years after its completion.[75]

Ten years after finishing his translation, Tolkien gave a highly acclaimed lecture on the work, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics", which had a lasting influence on Beowulf research.[76] Lewis E. Nicholson said that the article Tolkien wrote about Beowulf is "widely recognized as a turning point in Beowulfian criticism", noting that Tolkien established the primacy of the poetic nature of the work as opposed to its purely linguistic elements.[77] At the time, the consensus of scholarship deprecated Beowulf for dealing with childish battles with monsters rather than realistic tribal warfare; Tolkien argued that the author of Beowulf was addressing human destiny in general, not as limited by particular tribal politics, and therefore the monsters were essential to the poem.[78] Where Beowulf does deal with specific tribal struggles, as at Finnsburg, Tolkien argued firmly against reading in fantastic elements.[79] In the essay, Tolkien also revealed how highly he regarded Beowulf: "Beowulf is among my most valued sources", and this influence may be seen throughout his Middle-earth legendarium.[80]

According to Humphrey Carpenter, Tolkien began his series of lectures on Beowulf in a most striking way, entering the room silently, fixing the audience with a look, and suddenly declaiming in Old English the opening lines of the poem, starting "with a great cry of Hwæt!" It was a dramatic impersonation of an Anglo-Saxon bard in a mead hall, and it made the students realize that Beowulf was not just a set text but "a powerful piece of dramatic poetry".[81]

Decades later, W. H. Auden wrote to his former professor, thanking him for the "unforgettable experience" of hearing him recite Beowulf, and stating "The voice was the voice of Gandalf".[81]

Second World War

In the run-up to the Second World War, Tolkien was earmarked as a codebreaker.[82][83] In January 1939, he was asked whether he would be prepared to serve in the cryptographic department of the Foreign Office in the event of national emergency.[82][83] He replied in the affirmative and, beginning on 27 March, took an instructional course at the London HQ of the Government Code and Cypher School.[82][83] A record of his training was found which included the notation "keen" next to his name,[84] although Tolkien scholar Anders Stenström suggested that "In all likelihood, that is not a record of Tolkien's interest, but a note about how to pronounce the name."[85] He was informed in October that his services would not be required.[82][83]

In 1945, Tolkien moved to Merton College, Oxford, becoming the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature,[86] in which post he remained until his retirement in 1959. He served as an external examiner for University College, Dublin, for many years. In 1954 Tolkien received an honorary degree from the National University of Ireland (of which U.C.D. was a constituent college). Tolkien completed The Lord of the Rings in 1948, close to a decade after the first sketches.

Family

The Tolkiens had four children: John Francis Reuel Tolkien (17 November 1917 – 22 January 2003), Michael Hilary Reuel Tolkien (22 October 1920 – 27 February 1984), Christopher John Reuel Tolkien (21 November 1924 – 15 January 2020) and Priscilla Mary Anne Reuel Tolkien (born 18 June 1929). Tolkien was very devoted to his children and sent them illustrated letters from Father Christmas when they were young. Each year more characters were added, such as the North Polar Bear (Father Christmas's helper), the Snow Man (his gardener), Ilbereth the elf (his secretary), and various other, minor characters. The major characters would relate tales of Father Christmas's battles against goblins who rode on bats and the various pranks committed by the North Polar Bear.[87]

Retirement and later years

During his life in retirement, from 1959 up to his death in 1973, Tolkien received steadily increasing public attention and literary fame. In 1961, his friend C. S. Lewis even nominated him for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[88] The sales of his books were so profitable that he regretted that he had not chosen early retirement.[24] In a 1972 letter, he deplored having become a cult-figure, but admitted that "even the nose of a very modest idol ... cannot remain entirely untickled by the sweet smell of incense!"[89]

Fan attention became so intense that Tolkien had to take his phone number out of the public directory,[90] and eventually he and Edith moved to Bournemouth, which was then a seaside resort patronized by the British upper middle class. Tolkien's status as a best-selling author gave them easy entry into polite society, but Tolkien deeply missed the company of his fellow Inklings. Edith, however, was overjoyed to step into the role of a society hostess, which had been the reason that Tolkien selected Bournemouth in the first place. The genuine and deep affection between Ronald and Edith was demonstrated by their care about the other's health, in details like wrapping presents, in the generous way he gave up his life at Oxford so she could retire to Bournemouth, and in her pride in his becoming a famous author. They were tied together, too, by love for their children and grandchildren.[91]

In his retirement Tolkien was a consultant and translator for the Jerusalem Bible, published in 1966. He was initially assigned a larger portion to translate, but, due to other commitments, only managed to offer some criticisms of other contributors and a translation of the Book of Jonah.[92]

Final years

Edith died on 29 November 1971, at the age of 82. Ronald returned to Oxford, where Merton College gave him convenient rooms near the High Street. He missed Edith, but enjoyed being back in the city.[93]

Tolkien was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1972 New Year Honours[94] and received the insignia of the Order at Buckingham Palace on 28 March 1972.[95] In the same year Oxford University gave him an honorary Doctorate of Letters.[41][96]

He had the name Lúthien engraved on Edith's tombstone at Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford. When Tolkien died 21 months later on 2 September 1973 from a bleeding ulcer and chest infection,[97] at the age of 81,[98] he was buried in the same grave, with Beren added to his name. The engravings read:

Lúthien

1889–1971

John Ronald

Reuel Tolkien

Beren

1892–1973

Tolkien's will was proven on 20 December 1973, with his estate valued at £190,577 (equivalent to £2,321,707 in 2019).[99][100]

Views

Tolkien was a devout Roman Catholic, and in his religious and political views he was mostly a traditionalist moderate, with libertarian, distributist, localist, and monarchist leanings, in the sense of favouring established conventions and orthodoxies over innovation and modernization, whilst castigating government bureaucracy; in 1943 he wrote, "My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs)—or to 'unconstitutional' Monarchy."[101]

Although he did not often write or speak about it, Tolkien advocated the dismantling of the British Empire and even of the United Kingdom. In a 1936 letter to a former student, the Belgian linguist Simonne d'Ardenne, he wrote, "The political situation is dreadful... I have the greatest sympathy with Belgium—which is about the right size of any country! I wish my own were bounded still by the seas of the Tweed and the walls of Wales... we folk do at least know something of mortality and eternity and when Hitler (or a Frenchman) says 'Germany (or France) must live forever' we know that he lies."[102]

Tolkien hated the side effects of industrialization, which he considered to be devouring the English countryside and simpler life. For most of his adult life, he was disdainful of cars, preferring to ride a bicycle.[103] This attitude can be seen in his work, most famously in the portrayal of the forced "industrialization" of the Shire in The Lord of the Rings.[104]

Many commentators[105] have remarked on parallels between the Middle-earth saga and events in Tolkien's lifetime. The Lord of the Rings is often thought to represent England during and immediately after the Second World War. Tolkien rejected this in the foreword to the second edition of the novel, stating that he preferred applicability to allegory.[105] In his essay "On Fairy-Stories" he argued that fairy-stories are so apt because they are consistent both within themselves and with truths about reality, as Christianity itself is. Commentators have accordingly sought Christian themes in The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien objected to C. S. Lewis's use of overt religious allegory in his stories.[106] However, he wrote that the Mount Doom scene exemplified lines from the Lord's Prayer.[107][108]

His love of myths and his faith came together in his assertion that he believed mythology to be the divine echo of "the Truth",[109] a view expressed in his poem Mythopoeia.[110]

Religion

Tolkien's Roman Catholicism was a significant factor in C. S. Lewis's conversion from atheism to Christianity, although Tolkien was dismayed that Lewis chose to join the Church of England.[111]

He once wrote to Rayner Unwin's daughter Camilla, who wished to know the purpose of life, that it was "to increase according to our capacity our knowledge of God by all the means we have, and to be moved by it to praise and thanks."[112] He had a special devotion to the blessed sacrament, writing to his son Michael that in "the Blessed Sacrament ... you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth, and more than that".[113] He accordingly encouraged frequent reception of Holy Communion, again writing to his son Michael that "the only cure for sagging of fainting faith is Communion." He believed the Catholic Church to be true most of all because of the pride of place and the honour in which it holds the Blessed Sacrament. While he did not disparage the Second Vatican Council – describing it as "needed" – he felt that the reforms of Pope Pius X "surpass[ed] anything...that the Council will achieve."[114] In the last years of his life, Tolkien resisted some of the liturgical changes implemented after the Second Vatican Council, especially the use of English for the liturgy; he continued to make the responses in Latin, ignoring the rest of the congregation.[93]

Politics and race

Anti-communism

Tolkien voiced support for the Nationalists (eventually led by Franco during the Spanish Civil War) upon hearing that communist Republicans were destroying churches and killing priests and nuns.[115]

He was contemptuous of Joseph Stalin. During World War II, Tolkien referred to Stalin as "that bloodthirsty old murderer".[116] However, in 1961, Tolkien sharply criticized a Swedish commentator who suggested that The Lord of the Rings was an anti-communist parable and identified Sauron with Stalin, stating that the situation was conceived long before the Russian revolution.[117]

Opposition to globalization and technocracy

Tolkien was critical of technocracy and what he saw as the dual attempt to control the natural world through science and man through the state. "The quarrelsome, conceited Greeks managed to pull it off against Xerxes; but the abominable chemists and engineers have put such a power into Xerxes' hands...that decent folk don't seem to have a chance." He lamented that the state had become an increasingly abstract entity, and government had come to be thought of as a "thing" rather than a personal process.[118]

He bemoaned the globalization that was a result of the Second World War, writing that "the special horror of the present world is that the whole damned thing is in one bag. There is nowhere to fly to. Even the unlucky little Samoyedes, I suspect, have tinned food and the village loudspeaker telling Stalin's bed-time stories about Democracy and the wicked Fascists who eat babies and steal sledge-dogs."[118] Globalization was in his mind tied to the spread of American methods of mass production, standardization, and mass consumption, and the dominance of English.[119]

Opposition to Nazism

Tolkien vocally opposed Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party before the Second World War, and despised Nazi racist and anti-semitic ideology. In 1938, the publishing house Rütten & Loening, preparing to release The Hobbit in Nazi Germany, outraged Tolkien by asking him whether he was of Aryan origin. In a letter to his British publisher Stanley Unwin, he condemned Nazi "race-doctrine" as "wholly pernicious and unscientific". He added that he had many Jewish friends and was considering "letting a German translation go hang".[120] He provided two letters to Rütten & Loening and instructed Unwin to send whichever he preferred. The more tactful letter was sent but is now lost. In the unsent letter, Tolkien made the point that "Aryan" was a linguistic term, denoting speakers of Indo-Iranian languages, and stated that "if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people."[121] In a 1941 letter to his son Michael, he expressed his resentment at the distortion of Germanic history in "Nordicism", referring to "that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hitler ... Ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe, which I have ever loved, and tried to present in its true light."[122] In 1968, he objected to a description of Middle-earth as "Nordic" for a similar reason.[123]

Total war

Tolkien criticized Allied use of total-war tactics against civilians of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. In a 1945 letter to his son Christopher, he wrote that it was unacceptable to gloat over a criminal's or Germany's punishment, and that Germany's destruction, deserved or not, was an "appalling world-catastrophe".[124] He was horrified by the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, referring to the scientists of the Manhattan Project as "these lunatic physicists" and "Babel-builders".[125]

Democracy

Tolkien did not consider himself "a 'democrat' in any of its current uses". He saw the only true source of equality among men as equality before God.[126] For him, democracy did not lead to an increase in humility and power for the individual but rather to demagoguery and pride: "with the result [of democracy being] that we get not universal smallness and humility, but universal greatness and pride, till some Orc gets hold of a ring of power – and then we get and are getting slavery."[127]

Race

Tolkien reacted with anger to the excesses of anti-German propaganda during World War II. In a 1944 letter to Christopher, he compared the local press to the verbal excesses of Joseph Goebbels, pointing out that if they advocated exterminating Germans, they were no better than the Nazis themselves.[128]

He lamented the treatment of native Africans by whites in his native South Africa.[129]

Nature

During most of his own life conservationism was not yet on the political agenda, and Tolkien himself did not directly express conservationist views—except in some private letters, in which he tells about his fondness for forests and sadness at tree-felling. In later years, a number of authors of biographies or literary analyses of Tolkien conclude that during his writing of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien gained increased interest in the value of wild and untamed nature, and in protecting what wild nature was left in the industrialized world.[130][131][132]

Writing

Tolkien devised several themes that were reused in successive drafts of his legendarium, beginning with The Book of Lost Tales, written while recuperating from the illness contracted during The Battle of the Somme. The two most prominent stories, the tale of Beren and Lúthien and that of Túrin, were carried forward into long narrative poems (published in The Lays of Beleriand).

Influences

British adventure stories

One of the greatest influences on Tolkien was the Arts and Crafts polymath William Morris. Tolkien wished to imitate Morris's prose and poetry romances,[133] from which he took hints for the names of features such as the Dead Marshes in The Lord of the Rings[134] and Mirkwood,[135] along with some general aspects of approach. Edward Wyke-Smith's The Marvellous Land of Snergs, with its "table-high" title characters, strongly influenced the incidents, themes, and depiction of Bilbo's race in The Hobbit.[136] Tolkien mentioned H. Rider Haggard's novel She: "I suppose as a boy She interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas [Amenartas], which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving."[137] A supposed facsimile of this potsherd appeared in Haggard's first edition, and the ancient inscription it bore, once translated, led the English characters to She's ancient kingdom. Critics have compared this device to the Testament of Isildur in The Lord of the Rings[138] and to Tolkien's efforts to produce a facsimile page from the Book of Mazarbul.[139] Critics starting with Edwin Muir[140] have found resemblances between Haggard's romances and Tolkien's.[141][142][143]

Tolkien wrote of being impressed as a boy by S. R. Crockett's historical novel The Black Douglas and of basing the battle with the wargs in The Fellowship of the Ring partly on an incident in it.[144] Critics have noted the similarity in style of incidents in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings to the novel, and have suggested that it was influential.[145][146]

European mythology

Tolkien was inspired by early Germanic, especially Old English, literature, poetry, and mythology, his chosen and much-loved areas of expertise. These included Beowulf, Norse sagas such as the Volsunga saga and the Hervarar saga,[147] the Poetic Edda, the Prose Edda, and the Nibelungenlied.[148] Despite the similarities of his work to the Volsunga saga and the Nibelungenlied, the basis for Richard Wagner's opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, Tolkien dismissed critics' direct comparisons to Wagner, telling his publisher, "Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceases." However, some critics[149][150][151] believe that Tolkien was, in fact, indebted to Wagner for elements such as the "concept of the Ring as giving the owner mastery of the world ..."[152] Two characteristics of the One Ring, its inherent malevolence and its corrupting power upon minds and wills, were not present in the mythical sources but have a central role in Wagner's opera.

Tolkien acknowledged several non-Germanic sources for some of his stories and ideas. Sophocles' play Oedipus Rex he cited as inspiring elements of The Silmarillion and The Children of Húrin. He read William Forsell Kirby's translation of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala by Elias Lönnrot, while attending King Edward's School. He described its character of Väinämöinen as an influence for Gandalf the Grey, while its antihero Kullervo inspired Túrin Turambar.[153] Scholars such as Dimitra Fimi, Douglas A. Anderson, John Garth, and Marjorie Burns believe that Tolkien also drew influence from Celtic history and legends.[154][155] However, after the Silmarillion manuscript was rejected, in part for its "eye-splitting" Celtic names, he denied their Celtic origin, writing that he did know "Celtic things" including in Irish and Welsh, but he felt some distaste for their "fundamental unreason".[156][157] Fimi pointed out that despite this, Tolkien was fluent in medieval Welsh and declared when delivering the first O'Donnell lectures at Oxford in 1954 that Welsh was "beautiful".[154]

Tolkien objected to the description of his works as "Nordic", both for that term's racist and pagan undertones. Responding to a claim made in the Daily Telegraph Magazine that "the North is a sacred direction" in Tolkien's works, he claimed that his love of the North was based mainly on the fact that he was an inhabitant of northwestern Europe, and that the north was not sacred to him nor did it "exhaust [his] affections". He regarded the end of The Return of the King as akin to the re-establishment of the "Holy Roman Empire with its seat in Rome [more] than anything that would be devised by a 'Nordic'."[158]

One of Tolkien's purposes when writing his Middle-earth books was to create what his biographer Humphrey Carpenter called a "mythology for England". Carpenter cited Tolkien's letter to Milton Waldman complaining of the "poverty of my country: it had no stories of its own (bound up with its tongue and soil)" unlike the Celtic nations of Scotland, Ireland and Wales, which all had their own well developed mythologies.[154] Tolkien never used the exact phrase "a mythology for England", but often made statements to that effect, writing to one reader that his intention in writing the Middle-earth stories was "to restore to the English an epic tradition and present them with a mythology of their own".[154]

In the early 20th century, proponents of Irish nationalism like W. B. Yeats and Lady Gregory created a link in the public mind between traditional Irish folk tales of fairies and elves, and Irish national identity; they denigrating English folk tales as derivatives of Irish ones.[154] This prompted a backlash by English writers, leading to a war of words about which nation had the better fairy tales; the English essayist G. K. Chesterton exchanged polemical essays with Yeats over the question.[154] As a result, many people saw Irish mythology and folklore as Anglophobic.[154] Tolkien with his determination to write a "mythology for England" was for this reason disinclined to admit to Celtic influences.[154] Fimi noted in particular that the story of the Noldor, the Elves who fled Valinor for Middle-earth, resembles the story related in the Lebor Gabála Érenn of the semi-divine Tuatha Dé Danann who fled from a faraway place to conquer Ireland.[154] Like Tolkien's Elves, the Tuatha Dé Danann are inferior to the gods, but superior to humans, being endowed with extraordinary skills as craftsmen, poets, warriors, and magicians.[154] Likewise, after the triumph of humanity, both the Elves and the Tuatha Dé Danann are driven underground, which causes their "fading", leading them to become diminutive and pale.[154]

Catholicism

Catholic theology and imagery played a part in fashioning Tolkien's creative imagination, suffused as it was by his deeply religious spirit.[148][159]

Specifically, Paul H. Kocher argues that Tolkien describes evil in the orthodox Christian way as the absence of good. He cites many examples in The Lord of the Rings, such as Sauron's "Lidless Eye": "the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing". Kocher sees Tolkien's source as Thomas Aquinas, "whom it is reasonable to suppose that Tolkien, as a medievalist and a Catholic, knows well".[160] Tom Shippey makes the same point, but, instead of referring to Aquinas, says Tolkien was very familiar with Alfred the Great's Anglo-Saxon translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy, known as the Lays of Boethius. Shippey contends that this Christian view of evil is most clearly stated by Boethius: "evil is nothing". He says Tolkien used the corollary that evil cannot create as the basis of Frodo's remark, "the Shadow ... can only mock, it cannot make: not real new things of its own", and related remarks by Treebeard and Elrond.[161] He goes on to argue that in The Lord of the Rings evil does sometimes seem to be an independent force, more than merely the absence of good, and suggests that Alfred's additions to his translation of Boethius may have inspired that view.[162]

Stratford Caldecott also interpreted the Ring in theological terms: "The Ring of Power exemplifies the dark magic of the corrupted will, the assertion of self in disobedience to God. It appears to give freedom, but its true function is to enslave the wearer to the Fallen Angel. It corrodes the human will of the wearer, rendering him increasingly 'thin' and unreal; indeed, its gift of invisibility symbolizes this ability to destroy all natural human relationships and identity. You could say the Ring is sin itself: tempting and seemingly harmless to begin with, increasingly hard to give up and corrupting in the long run."[163]

Publications

"Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics"

In addition to writing fiction, Tolkien was an author of academic literary criticism. His seminal 1936 lecture, later published as an article, revolutionized the treatment of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf by literary critics. The essay remains highly influential in the study of Old English literature to this day. Beowulf is one of the most significant influences upon Tolkien's later fiction, with major details of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings being adapted from the poem.

"On Fairy-Stories"

This essay discusses the fairy-story as a literary form. It was initially written as the 1939 Andrew Lang Lecture at the University of St Andrews, Scotland.

Tolkien focuses on Andrew Lang's work as a folklorist and collector of fairy tales. He disagreed with Lang's broad inclusion, in his Fairy Book collections, of traveller's tales, beast fables, and other types of stories. Tolkien held a narrower perspective, viewing fairy stories as those that took place in Faerie, an enchanted realm, with or without fairies as characters. He viewed them as the natural development of the interaction of human imagination and human language.

Children's books and other short works

In addition to his mythopoeic compositions, Tolkien enjoyed inventing fantasy stories to entertain his children.[164] He wrote annual Christmas letters from Father Christmas for them, building up a series of short stories (later compiled and published as The Father Christmas Letters). Other works included Mr. Bliss and Roverandom (for children), and Leaf by Niggle (part of Tree and Leaf), The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, Smith of Wootton Major and Farmer Giles of Ham. Roverandom and Smith of Wootton Major, like The Hobbit, borrowed ideas from his legendarium.

The Hobbit

Tolkien never expected his stories to become popular, but by sheer accident a book called The Hobbit, which he had written some years before for his own children, came in 1936 to the attention of Susan Dagnall, an employee of the London publishing firm George Allen & Unwin, who persuaded Tolkien to submit it for publication.[98] When it was published a year later, the book attracted adult readers as well as children, and it became popular enough for the publishers to ask Tolkien to produce a sequel.

The Lord of the Rings

The request for a sequel prompted Tolkien to begin what would become his most famous work: the epic novel The Lord of the Rings (originally published in three volumes 1954–1955). Tolkien spent more than ten years writing the primary narrative and appendices for The Lord of the Rings, during which time he received the constant support of the Inklings, in particular his closest friend C. S. Lewis, the author of The Chronicles of Narnia. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are set against the background of The Silmarillion, but in a time long after it.

Tolkien at first intended The Lord of the Rings to be a children's tale in the style of The Hobbit, but it quickly grew darker and more serious in the writing.[165] Though a direct sequel to The Hobbit, it addressed an older audience, drawing on the immense backstory of Beleriand that Tolkien had constructed in previous years, and which eventually saw posthumous publication in The Silmarillion and other volumes. Tolkien's influence weighs heavily on the fantasy genre that grew up after the success of The Lord of the Rings.

The Lord of the Rings became immensely popular in the 1960s and has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the 20th century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.[166] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the UK's "Best-loved Novel".[167] Australians voted The Lord of the Rings "My Favourite Book" in a 2004 survey conducted by the Australian ABC.[168] In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to be their favourite "book of the millennium".[169] In 2002 Tolkien was voted the 92nd "greatest Briton" in a poll conducted by the BBC, and in 2004 he was voted 35th in the SABC3's Great South Africans, the only person to appear in both lists. His popularity is not limited to the English-speaking world: in a 2004 poll inspired by the UK's "Big Read" survey, about 250,000 Germans found The Lord of the Rings to be their favourite work of literature.[170]

Posthumous publications

The Silmarillion

Tolkien wrote a brief "Sketch of the Mythology", which included the tales of Beren and Lúthien and of Túrin; and that sketch eventually evolved into the Quenta Silmarillion, an epic history that Tolkien started three times but never published. Tolkien desperately hoped to publish it along with The Lord of the Rings, but publishers (both Allen & Unwin and Collins) declined. Moreover, printing costs were very high in 1950s Britain, requiring The Lord of the Rings to be published in three volumes.[171] The story of this continuous redrafting is told in the posthumous series The History of Middle-earth, edited by Tolkien's son, Christopher Tolkien. From around 1936, Tolkien began to extend this framework to include the tale of The Fall of Númenor, which was inspired by the legend of Atlantis.

Tolkien had appointed his son Christopher to be his literary executor, and he (with assistance from Guy Gavriel Kay, later a well-known fantasy author in his own right) organized some of this material into a single coherent volume, published as The Silmarillion in 1977. It received the Locus Award for Best Fantasy novel in 1978.[172]

Unfinished Tales and The History of Middle-earth

In 1980, Christopher Tolkien published a collection of more fragmentary material, under the title Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth. In subsequent years (1983–1996), he published a large amount of the remaining unpublished materials, together with notes and extensive commentary, in a series of twelve volumes called The History of Middle-earth. They contain unfinished, abandoned, alternative, and outright contradictory accounts, since they were always a work in progress for Tolkien and he only rarely settled on a definitive version for any of the stories. There is not complete consistency between The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, the two most closely related works, because Tolkien never fully integrated all their traditions into each other. He commented in 1965, while editing The Hobbit for a third edition, that he would have preferred to rewrite the book completely because of the style of its prose.[173]

The Children of Húrin

More recently, in 2007, The Children of Húrin was published by HarperCollins (in the UK and Canada) and Houghton Mifflin (in the US). The novel tells the story of Túrin Turambar and his sister Nienor, children of Húrin Thalion. The material was compiled by Christopher Tolkien from The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, The History of Middle-earth, and unpublished manuscripts.

The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún

The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, which was released worldwide on 5 May 2009 by HarperCollins and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, retells the legend of Sigurd and the fall of the Niflungs from Germanic mythology. It is a narrative poem composed in alliterative verse and is modelled after the Old Norse poetry of the Elder Edda. Christopher Tolkien supplied copious notes and commentary upon his father's work.

According to Christopher Tolkien, it is no longer possible to trace the exact date of the work's composition. On the basis of circumstantial evidence, he suggests that it dates from the 1930s. In his foreword he wrote, "He scarcely ever (to my knowledge) referred to them. For my part, I cannot recall any conversation with him on the subject until very near the end of his life, when he spoke of them to me, and tried unsuccessfully to find them."[174]

The Fall of Arthur

The Fall of Arthur, published on 23 May 2013, is a long narrative poem composed by Tolkien in the early-1930s. It is alliterative, extending to almost 1,000 lines imitating the Old English Beowulf metre in Modern English. Though inspired by high medieval Arthurian fiction, the historical setting of the poem is during the Post-Roman Migration Period, both in form (using Germanic verse) and in content, showing Arthur as a British warlord fighting the Saxon invasion, while it avoids the high medieval aspects of the Arthurian cycle (such as the Grail, and the courtly setting); the poem begins with a British "counter-invasion" to the Saxon lands (Arthur eastward in arms purposed).[175]

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, published on 22 May 2014, is a prose translation of the early medieval epic poem Beowulf from Old English to modern English. Translated by Tolkien from 1920 to 1926, it was edited by his son Christopher. The translation is followed by over 200 pages of commentary on the poem; this commentary was the basis of Tolkien's acclaimed 1936 lecture "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics".[176] The book also includes the previously unpublished "Sellic Spell" and two versions of "The Lay of Beowulf". The former is a fantasy piece on Beowulf's biographical background, while the latter is a poem on the Beowulf theme.[177]

The Story of Kullervo

The Story of Kullervo, first published in Tolkien Studies in 2010 and reissued with additional material in 2015, is a retelling of a 19th-century Finnish poem. It was written in 1915 while Tolkien was studying at Oxford.[178]

Beren and Lúthien

The Tale of Beren and Lúthien is one of the oldest and most often revised in Tolkien's legendarium. The story is one of three contained within The Silmarillion which Tolkien believed to warrant their own long-form narratives. It was published as a standalone book, edited by Christopher Tolkien, under the title Beren and Lúthien in 2017.[179]

The Fall of Gondolin

The Fall of Gondolin is a tale of a beautiful, mysterious city destroyed by dark forces, which Tolkien called "the first real story" of Middle-earth, was published on 30 August 2018[180] as a standalone book, edited by Christopher Tolkien and illustrated by Alan Lee.[181]

Manuscript locations

Before his death, Tolkien negotiated the sale of the manuscripts, drafts, proofs and other materials related to his then-published works—including The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit and Farmer Giles of Ham—to the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Marquette University's John P. Raynor, S.J., Library in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[182] After his death his estate donated the papers containing Tolkien's Silmarillion mythology and his academic work to the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.[183] The Library held an exhibition of his work in 2018, including more than 60 items which had never been seen in public before.[184]

In 2009, a partial draft of Language and Human Nature, which Tolkien had begun co-writing with C. S. Lewis but had never completed, was discovered at the Bodleian Library.[185]

Languages and philology

Linguistic career

Both Tolkien's academic career and his literary production are inseparable from his love of language and philology. He specialized in English philology at university and in 1915 graduated with Old Norse as his special subject. He worked on the Oxford English Dictionary from 1918 and is credited with having worked on a number of words starting with the letter W, including walrus, over which he struggled mightily.[186] In 1920, he became Reader in English Language at the University of Leeds, where he claimed credit for raising the number of students of linguistics from five to twenty. He gave courses in Old English heroic verse, history of English, various Old English and Middle English texts, Old and Middle English philology, introductory Germanic philology, Gothic, Old Icelandic, and Medieval Welsh. When in 1925, aged thirty-three, Tolkien applied for the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Oxford, he boasted that his students of Germanic philology in Leeds had even formed a "Viking Club".[187] He also had a certain, if imperfect, knowledge of Finnish.[188]

Privately, Tolkien was attracted to "things of racial and linguistic significance", and in his 1955 lecture English and Welsh, which is crucial to his understanding of race and language, he entertained notions of "inherent linguistic predilections", which he termed the "native language" as opposed to the "cradle-tongue" which a person first learns to speak.[189] He considered the West Midlands dialect of Middle English to be his own "native language", and, as he wrote to W. H. Auden in 1955, "I am a West-midlander by blood (and took to early west-midland Middle English as a known tongue as soon as I set eyes on it)."[190]

Language construction

Parallel to Tolkien's professional work as a philologist, and sometimes overshadowing this work, to the effect that his academic output remained rather thin, was his affection for constructing languages. The most developed of these are Quenya and Sindarin, the etymological connection between which formed the core of much of Tolkien's legendarium. Language and grammar for Tolkien was a matter of aesthetics and euphony, and Quenya in particular was designed from "phonaesthetic" considerations; it was intended as an "Elvenlatin", and was phonologically based on Latin, with ingredients from Finnish, Welsh, English, and Greek.[157] A notable addition came in late 1945 with Adûnaic or Númenórean, a language of a "faintly Semitic flavour", connected with Tolkien's Atlantis legend, which by The Notion Club Papers ties directly into his ideas about the inability of language to be inherited, and via the "Second Age" and the story of Eärendil was grounded in the legendarium, thereby providing a link of Tolkien's 20th-century "real primary world" with the legendary past of his Middle-earth.

Tolkien considered languages inseparable from the mythology associated with them, and he consequently took a dim view of auxiliary languages: in 1930 a congress of Esperantists were told as much by him, in his lecture A Secret Vice,[191] "Your language construction will breed a mythology", but by 1956 he had concluded that "Volapük, Esperanto, Ido, Novial, &c, &c, are dead, far deader than ancient unused languages, because their authors never invented any Esperanto legends".[192]

The popularity of Tolkien's books has had a small but lasting effect on the use of language in fantasy literature in particular, and even on mainstream dictionaries, which today commonly accept Tolkien's idiosyncratic spellings dwarves and dwarvish (alongside dwarfs and dwarfish), which had been little used since the mid-19th century and earlier. (In fact, according to Tolkien, had the Old English plural survived, it would have been dwarrows or dwerrows.) He also coined the term eucatastrophe, though it remains mainly used in connection with his own work.

Artwork