Let's begin with Dr. Seuss and then explore several other writers

of the limerick genre. - re slater

ps - "Can you find the non-limerick panel(s) which don't belong?"

Happy Birthday, Dr. Seuss!

Today is the birthday of old Dr. Seuss,

A man of many words, all put to good use.

Books with dark-lit windows and too many doors,

With upstairs and downstairs and too many floors.

Using words like "Once-ler" and "Sneetches" is silly at times,

But words such as these make for silly ol’ rhymes.

Creatively described on the house and the lawn,

Duck feet and Fox in Socks ingeniously drawn.

Children don’t question Geisel’s word choices he makes,

"DiffenDoofer" and "Octember" reveal no mistakes.

He writes without misspelling, he writes with no wrongs,

He constructs silly sentences, stringing new words along.

With creative new words, you’ll find that you’ll laugh,

With The Cat in the Hat and on Yertle the Turtle’s behalf.

No challenge is too challenging in writing a plot,

Impactful and impressive is Ten Apples Up on Top.

Horton hatches the egg because he said that he would,

Be careful of words like "I could" and "I should".

"I can" and "I will" is the way to success,

A Wacky Wednesday is meant to lessen the stress.

Oh, the Places You’ll Go if you just take a look

At The 500 Hats and The Tooth and Eye Book.

Impressions LeSieg has made on so many,

With a cat and the Lorax and characters of plenty.

Oh the Thinks you can Think, and all that you’ve earned,

Comes from reading and loving all the things that you’ve learned.

You’re Only Old Once, so dive into McElligot’s Pool,

Be open to adventure on your way to Solla Sollew.

Meet Thidwick and Horton, and Thing One and Thing Two,

Meet Mr. Brown and Marco, Daisy-Head Mayzie and Sue.

I Can Read with My Eyes Shut because you said that I could,

I’ve tasted Green Eggs and Ham because you insisted I should.

I can count One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish,

And pretend There’s A Wocket in my Pocket, if I wish.

Dr. Seuss, I’d like to thank you for all the things I could do,

Like reading A, B, C’s and imagining If I Ran the Zoo.

And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street with you,

Theodor Geisel, today, I wish a happy birthday to you!

* * * * * * * *

A Sense for Nonsense:

From Edward Lear to Lewis Carroll to Dr. Seuss

by Dale D. Dalenberg, M.D.

April 1, 2014

Every now and then the Dalenberg Library of Antique Popular Literature gets ambitious and tries to live up to its name by buying something that is truly antique. This month we are proud to announce the acquisition of a first edition of Lewis Carroll’s book-length nonsense poem masterpiece The Hunting of the Snark (MacMillan and Co., London, 1876.) To be precise, the real first edition was a limited run bound in red that is very pricey to come by these days, but our copy is from the main press run bound between tan brown boards with front and back cover illustrations, gilt on all edges, and including nine interior panels illustrated by Henry Holiday (1839-1927), who was associated with the pre-Raphaelite group of Victorian artists.

Snark is Lewis Carroll’s most famous and popular work outside of the two Alice in Wonderland books. The Holiday illustrations are priceless, quite unlike his other paintings, which were very much in the Edward Burne-Jones school of late Victorian sensual, romanticized realism. If you like the classic Tenniel illustrations for the Wonderland books, you will find the Holiday illustrations for the Snark poem to be in a similar vein, only more grotesque. An added treat in this edition is a little leaflet that has been attached to the front endpapers, dated Easter, 1876, and titled “An Easter Greeting to Every Child Who Loves ‘Alice’.” While I suspect that mostly adults with an interest in 19th Century literature read The Hunting of the Snark these days, Carroll obviously intended it to be for the same youthful audience who inspired the Wonderland tales.

|

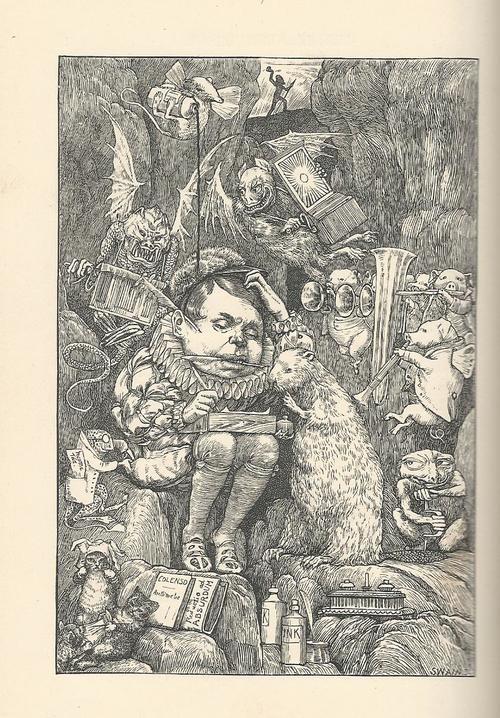

| “The Beaver’s Lesson” from The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll; illustrated by Henry Holiday |

Henry Holiday’s interpretation of “The Beaver’s Lesson” from The Hunting of the Snark, bearing more resemblance to something by Hieronymus Bosch than to his fellow pre-Raphaelites. The lines that inspired this plate:

The Beaver brought paper, portfolio, pens,

And ink in unfailing supplies:

While strange creepy creatures came out of their dens,

And watched them with wondering eyes.

The Hunting of the Snark recounts a nonsensical voyage in search of a mysterious beast, and it builds to a rather unexpected climax. As the story of a whimsical voyage, it is much more complex than - but still very reminiscent of - Edward Lear’s poem “The Jumblies,” which was written a few years earlier. The Jumblies go to sea in a sieve, which of course allows the water to get into their boat, but they manage to sleep in a crockery pot, somehow stay dry and alive, get to their destination, go shopping, buy some strange things (including a monkey with lollipop paws), and they come back home in twenty years having grown somewhat taller. In contrast, the crew of the Snark has a stranger, darker, more mysterious voyage, and the outcome is much less certain.

Edward Lear (1812-1888) is chiefly remembered and endlessly anthologized as the author of two poems published originally as “nonsense songs” in 1871. These are “The Owl and the Pussycat” (who also venture out to sea in the beginning of their poem) and “The Jumblies.” During his lifetime, Lear was predominantly a painter of animals and landscapes. He happened into writing by chance. While employed painting the avian collection and menagerie of the Earl of Derby, he took to writing nonsense limericks illustrated with pen drawings to amuse the children in the Earl’s family. The limericks were not published for 10 years (appearing in 1846). A second book didn’t appear until 16 years later (1862). By then, Lear must have had a following, because he trickled out a steady stream of nonsense stuff after his second book until his death in 1888.

Lear was a pioneer of this sort of whimsical writing. Lear is good, and in his time he had few if any competitors writing nonsense lyrics; but aside from a couple masterpieces, Lear is not great. His two famous poems are really his best, and there are not a great many other hidden gems. Mostly, his kind of writing has been improved upon by people who came along later and did his sort of poem better (such as Lewis Carroll, Eugene Field, Ogden Nash, and Dr. Seuss.)

Easily half of Lear’s nonsense output was limericks. He wrote more than two hundred. He was an early popularizer of the limerick, but he did not contribute much to its creativity. Most of his limericks are crafted in the old mold (going back to Mother Goose and before) of repeating the first line in the last line, often with a little variation. Unfortunately, this structure rather has the effect of making the last line anticlimactic because you have heard it before, like a joke without a surprise in the punchline. Lear’s limericks are silly and nonsensical, and the line drawings that accompany them are cute, but they are mostly not particularly funny.

Here are three of Lear’s limericks as originally written. Then I will follow with the Dale Dalenberg “improvements,” designed to demonstrate how replacing the repetitive final line with a new rhyming “punchline” can make the limerick both more interesting and more funny.

Edward Lear:

There was an Old Man on whose nose,

Most birds of the air could repose;

But they all flew away

At the closing of day,

Which relieved that Old Man and his nose.

Dalenberg version:

There was an Old Man on whose nose,

Most birds of the air could repose;

But they all flew away

At the closing of day,

Leaving night’s share of bird-stuff to hose.

Edward Lear:

There was an Old Person of Burton,

Whose answers were rather uncertain;

When they said, “How d’ye do?”

He replied, “Who are you?”

That distressing Old Person of Burton.

Dalenberg version:

There was an Old Person of Burton,

Whose answers were rather uncertain;

When they said, “How d’ye do?”

He replied, “Who are you?”

“Is he daft?” all would ask. “No—impertinent!”

Edward Lear:

There was an Old Person of Hurst,

Who drank when he was not athirst;

When they said, “You’ll grow fatter!”

He answered, “What matter?”

That globular Person of Hurst.

Dalenberg version:

There was an old Person of Hurst,

Who drank when he was not athirst;

When they said, “You’ll grow fatter!”

He answered, “What matter?”

They replied: “Keep it up and you’ll burst!”

Limericks were around before Edward Lear. Supposedly they first appeared in England in the early 18th Century. It is said that as folklore poetry, limericks were always raunchy. Lear took them out of the gutter and popularized the form as nonsense poems.

Despite moving from the pub to the nursery, ribald limericks do still persist today. They are rather addictive to compose, and generally when you start, you keep coming up with more.

I wrote a handful of raunchy ones for this blog, but I can’t publish most of them here, because we try to run a family-friendly blog. Still, I’ll push the limits with three of the cleanest of my naughty limericks, just to demonstrate and play with the form. These are my R-rated ones, not my X-rated ones (feel free to send me an e-mail request for those.) Two of these use the punch-line approach, and the other uses the repeated last-line approach (with a twist):

There was an unsatisfied suitor

Who returned to the girl’s house to shoot her,

But his crime proved a botch

When SHE aimed at HIS crotch

And inquired, “Is it better to spay or to neuter?”

There was a young man of Hong Kong

Who was oppressed by his over-sized schlong,

‘Til he sliced off his testes,

Took hormones, grew breast-ies,

Now he is a young girl of Hong Kong.

Two Sisters from down around Natchez

Turned tricks with their tongues and their snatches,

And sometimes for fun

They’d charge 2-for-1

And bang all the Brothers in batches.

Hallmarks of the limerick include a general sense of irreverence, caricature, and a mockery of more serious academic devices. Many limericks play fast and loose with geography and place names, for instance. Rather than telling us anything about the place, however, the place name is usually just there for rhyming purposes. Thus we have the classic limerick parody line, “There was a young man of Nantucket. . .”, which tells us nothing about Nantucket, but the place name is in the poem mostly just to rhyme with a variety of really vulgar phrases that can be used to end the next line. The word-play of the limerick, and the fact that random things must be plucked out of the air and plunked down in the poem just to fit the rhyme scheme, lends the form to nonsense content. Once you get into the idiom, it’s just as easy to write silly limericks as dirty ones. With apologies to the Japanese, here is one of my silly (non-filthy) limericks:

Drunk wrestler of sumo on saké

Ate way too much teriyaki,

Kept feeding and feeding,

Just wouldn’t stop eating—

And that’s how he got so damn stocky.

---

Lewis Carroll (the pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, 1832-1898) improved on the nonsense poetry model that Lear established in poems like “The Jumblies.” Carroll’s work incorporates mathematical puzzles, political allegory, and mysterious in-jokes into a more fully realized fantasy landscape. Lewis Carroll’s “portmanteau words” are a lot like some of Lear’s nonsense words (e.g. “runcible spoon”), only with a more complex etymology.

|

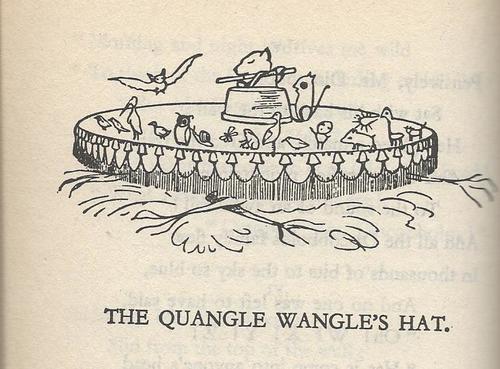

| poem by limerick poet Edward Lear |

Not quite sure what it is about nonsense poetry and beavers, but the opening lines go like this:

On the top of the Crumpetty Tree

The Quangle Wangle sat,

But his face you could not see,

On account of his Beaver Hat.

Edward Lear’s influence can be felt far beyond Carroll, however. With his simple line drawings, he is a precursor to more modern author-illustrators of childrens’ books, such as Dr. Seuss. In fact, Seuss’s Thidwick, the Big-Hearted Moose is a fleshed-out retelling of Edward Lear’s poem “The Quangle Wangle’s Hat,” with a twist.

In the Lear poem, a creature called the Quangle Wangle wears a beaver hat that is a hundred and two feet wide, and numerous animals come to live on the brim of the hat. In the Lear version they all have a grand old time, and the Quangle Wangle is perfectly happy to have guests.

But Dr. Seuss takes the material in a different direction as the animals take advantage of Thidwick’s good nature and become freeloader guests over-staying their welcome. Lear’s emphasis is on nonsense. That is also Dr. Seuss’s emphasis, even though Seuss usually tells a story with a moral—he just doesn’t lay it on too thick.

The moral is there in Thidwick—something like “don’t allow yourself to be a pushover and get taken advantage of by freeloader ‘friends’”—but the emphasis is still on the silly story, the whimsical illustrations, and the word-play.

* * * * * * * *

10 of the Best Nonsense Poems in English Literature

Are these the best examples of nonsense verse in English?

Selected by Dr Oliver Tearle

Nonsense literature is one of the great subsets of English literature, and for many of us a piece of nonsense verse is our first entry into the world of poetry. In this post, we’ve selected ten of the greatest works of nonsense poetry. We’ve omitted several names from this list, including Dr Seuss (because his best nonsense verse, whilst brilliant, is longer than the short-poem form, often comprising book-length narratives), Hilaire Belloc (whose best work is best-understood as part of the ‘cautionary verse’ tradition, which isn’t as nonsensical as bona fide nonsense verse), and Ogden Nash, whose work seems to be less in the nonsense verse tradition than more straightforward comic verse.

Some of these suggestions come courtesy of Quentin Blake’s The Puffin Book of Nonsense Verse (Puffin Poetry) , which we’d recommend to any fans of nonsense verse looking for an anthology of beautiful nonsense.

, which we’d recommend to any fans of nonsense verse looking for an anthology of beautiful nonsense.

, which we’d recommend to any fans of nonsense verse looking for an anthology of beautiful nonsense.

, which we’d recommend to any fans of nonsense verse looking for an anthology of beautiful nonsense.Hey, diddle, diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon;

The little dog laughed

To see such sport,

And the dish ran away with the spoon.

We tend to associate nonsense verse with those great nineteenth-century practitioners, Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, forgetting that many of the best nursery rhymes are also classic examples of nonsense literature. ‘Hey Diddle Diddle’, with its bovine athletics and eloping cutlery and crockery, certainly qualifies as nonsense.

‘Hey Diddle Diddle’ may have been the rhyme referred to in Thomas Preston’s 1569 play, "A lamentable tragedy mixed ful of pleasant mirth, conteyning the life of Cambises King of Percia: ‘They be at hand Sir with stick and fiddle; / They can play a new dance called hey-didle-didle.’" If so, this poem is much older than Victorian nonsense verse!

What does this intriguing nursery rhyme mean, if anything? What are its origins? We explore the history of this classic piece of nonsense verse for children in the link to the nursery rhyme provided above.

I Saw a Peacock, with a fiery tail,

I saw a Blazing Comet, drop down hail,

I saw a Cloud, with Ivy circled round,

I saw a sturdy Oak, creep on the ground,

I saw a Pismire, swallow up a Whale,

I saw a raging Sea, brim full of Ale …

Included in Quentin Blake’s anthology, this poem dates from the seventeenth century: ‘I Saw a Peacock, with a fiery tail, / I saw a Blazing Comet, drop down hail, / I saw a Cloud, with Ivy circled round, / I saw a sturdy Oak, creep on the ground …’

This is sometimes known as a ‘trick’ poem: look at how the second clause of each line describes the following object as well as the previous one, so that, for instance, ‘with a fiery tail’ could refer back to the peacock but also forwards to the ‘Blazing Comet’. We delve into the poem and its history in more detail in the link above.

So she went into the garden

to cut a cabbage-leaf

to make an apple-pie;

and at the same time

a great she-bear, coming down the street,

pops its head into the shop.

What! no soap?

So he died …

So begins this piece of ‘nonsense verse’. Although Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear are the names that immediately spring to mind, several eighteenth-century writers should get a mention in the history of nonsense writing. One is Henry Carey, who among other things coined the phrase ‘namby-pamby’ in his lambasting of the infantile verses of his contemporary, Ambrose Philips; another is the playwright Samuel Foote, known as the ‘English Aristophanes’, who lost one of his legs in an accident but took it good-humouredly, and often made jokes about it.

It was Samuel Foote who gave us ‘The Great Panjandrum’, a piece of writing whose influence arguably stretches to Carroll and Lear in the nineteenth century, and Spike Milligan in the twentieth. In the eighteenth century, Foote penned this piece of nonsense – later turned into verse simply by introducing line-breaks – as a challenge to the actor Charles Macklin, who boasted that he could memorise and recite any speech, after hearing it just once.

Click on the link above to read both the prose and verse version, and learn more about the origins of this piece of nonsense.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

‘If this were only cleared away,’

They said, ‘it would be grand!’

‘If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year,

Do you suppose,’ the Walrus said,

‘That they could get it clear?’

‘I doubt it,’ said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear …

Perhaps, of all Lewis Carroll’s poems, ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ has attracted the most commentary and speculation concerning its ultimate ‘meaning’. Some commentators have interpreted the predatory walrus and carpenter as representing, respectively, Buddha (because the walrus is large) and Jesus (the carpenter being the trade Jesus was raised in). It’s unlikely that this was Carroll’s intention, not least because the carpenter could easily have been a butterfly or a baronet instead: he actually gave his illustrator, John Tenniel, the choice, so it was Tenniel who selected ‘carpenter’.

In the poem, the two title characters, while walking along a beach, find a bed of oysters and proceed to eat the lot. But we’re clearly in a nonsense-world here, a world of fantasy: the sun and the moon are both out on this night. The oysters can walk and even wear shoes, even though they don’t have any feet. No, they don’t have feet, but they do have ‘heads’, and are described as being in their beds – with ‘bed’ here going beyond the meaning of ‘sea bed’ and instead conjuring up the absurdly comical idea of the oysters tucked up in bed asleep.

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

‘Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!’ …

Another classic poem by Lewis Carroll, ‘Jabberwocky’ is perhaps the most famous piece of nonsense verse in the English language. And the English language here is made to do some remarkable things, thanks to Carroll’s memorable coinages: it was this poem that gave the world the useful words ‘chortle’ and ‘galumph’, both examples of ‘blending’ or ‘portmanteau words’.

As we explain in the summary of the poem provided in the above link, ‘Jabberwocky’ may be nonsense verse but it also tells one of the oldest and most established stories in literature: the ‘overcoming the monster’ narrative and the ‘voyage and return’ plot. We also include a handy glossary of the nonsense words Carroll used in – and invented for – the poem.

The Owl and the Pussy-cat went to sea

In a beautiful pea-green boat,

They took some honey, and plenty of money,

Wrapped up in a five-pound note …

This is probably Edward Lear’s most famous poem, and a fine example of Victorian nonsense verse. It was published in Lear’s 1871 collection Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany, and Alphabets, and tells of the love between the owl and the pussycat and their subsequent marriage, with the turkey presiding over the wedding.

Edward Lear wrote ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’ for a friend’s daughter, Janet Symonds (daughter of the poet John Addington Symonds), who was born in 1865 and was three years old when Lear wrote the poem.

Long years ago

The Dong was happy and gay,

Till he fell in love with a Jumbly Girl

Who came to those shores one day.

For the Jumblies came in a sieve, they did, —

Landing at eve near the Zemmery Fidd

Where the Oblong Oysters grow,

And the rocks are smooth and gray …

One of the things which differentiates some of Lear’s nonsense verse from Lewis Carroll’s is the poignant strain of melancholy found in some of his finest poems. This nonsense poem is also a story of lost love, involving the titular Dong, a creature with a long glow-in-the-dark nose (fashioned from tree-bark and a lamp), who falls in love with the Jumbly girl, only to be abandoned by her.

Though some at my aversion smile,

I cannot love the crocodile.

Its conduct does not seem to me

Consistent with sincerity …

A. E. Housman, the poet best-known for A Shropshire Lad (1896), wrote poems about death and hopeless love. What [most don't know is] that A. E. Housman wrote nonsense verse [too]. In fact, Housman was an accomplished writer of light verse for children, and ‘The Crocodile’, subtitled ‘Public Decency’, is probably his finest piece of nonsense verse, with a cruel and macabre turn.

Although he’s more famous for writing fiction – notably the Gothic fantasy trilogy Gormenghast – Mervyn Peake was also a writer of nonsense verse. The link above will take you to several of Peake’s nonsense poems, but here we’ve chosen ‘The Trouble with Geraniums’ – which isn’t entirely about geraniums, but rather ‘the trouble with’ all sorts of things, from toast to diamonds to the poet’s looking-glass…

When he wasn’t entertaining millions as part of the comedy troupe the Goons, Spike Milligan was a talented author of nonsense verse, with this poem, first published in his 1959 collection Silly Verse for Kids, being perhaps his most celebrated example of the form. Indeed, in 2007 In December 2007 OFSTED reported that it was one of the ten most commonly taught poems in primary schools in the UK!

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History

and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

No comments:

Post a Comment