Dec 15, 2010Beethoven - Moonlight Sonata (FULL) - Piano Sonata No. 14Copyright Andrea Romano

The Piano Sonata No. 14 in C♯ minor "Quasi una fantasia", op. 27, No. 2 has three movements:0:00 1 mvt: Adagio sostenuto6:00 2 mvt: Allegretto8:05 3 mvt: Presto agitato

- Wikipedia (below)

- History of the Moonlight Sonata - https://www.tonara.com/blog/history-of-moonlight-sonata/

| Piano Sonata No. 14 | |

|---|---|

| Sonata quasi una fantasia | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

Title page of the first edition of the score, published on 2 August 1802 in Vienna by Giovanni Cappi e Comp[a] | |

| Other name | Moonlight Sonata |

| Key | C♯ minor, D♭ major (second movement) |

| Opus | 27/2 |

| Style | Classical-Romantic (transitional) |

| Form | Piano sonata |

| Composed | 1801 |

| Dedication | Countess Giulietta Guicciardi |

| Published | 1802 |

| Publisher | Giovanni Cappi |

| Duration | 15 minutes |

| Movements | 3 |

The Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, marked Quasi una fantasia, Op. 27, No. 2, is a piano sonata by Ludwig van Beethoven, completed in 1801 and dedicated in 1802 to his pupil Countess Julie "Giulietta" Guicciardi.[b] Although known throughout the world as the Moonlight Sonata (German: Mondscheinsonate), it was not Beethoven who named it so. The title "Moonlight Sonata'" was proposed in 1832, after the author's death, by the poet Ludwig Rellstab.

The piece is one of Beethoven's most famous compositions for the piano, and was quite popular even in his own day.[2] Beethoven wrote the Moonlight Sonata around the age of 30, after he had finished with some commissioned work; there is no evidence that he was commissioned to write this sonata.[2]

Names

The first edition of the score is headed Sonata quasi una fantasia ("sonata almost a fantasy"), the same title as that of its companion piece, Op. 27, No. 1.[3] Grove Music Online translates the Italian title as "sonata in the manner of a fantasy".[4] "The subtitle reminds listeners that the piece, although technically a sonata, is suggestive of a free-flowing, improvised fantasia."[5]

Many sources say that the nickname Moonlight Sonata arose after the German music critic and poet Ludwig Rellstab likened the effect of the first movement to that of moonlight shining upon Lake Lucerne.[6][7] This comes from the musicologist Wilhelm von Lenz, who wrote in 1852: "Rellstab compares this work to a boat, visiting, by moonlight, the remote parts of Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. The soubriquet Mondscheinsonate, which twenty years ago made connoisseurs cry out in Germany, has no other origin."[8][9] Taken literally, "twenty years" would mean the nickname had to have started after Beethoven's death. In fact Rellstab made his comment about the sonata's first movement in a story called Theodor that he published in 1824: "The lake reposes in twilit moon-shimmer [Mondenschimmer], muffled waves strike the dark shore; gloomy wooded mountains rise and close off the holy place from the world; ghostly swans glide with whispering rustles on the tide, and an Aeolian harp sends down mysterious tones of lovelorn yearning from the ruins."[8][10] Rellstab made no mention of Lake Lucerne, which seems to have been Lenz's own addition. Rellstab met Beethoven in 1825,[11] making it theoretically possible for Beethoven to have known of the moonlight comparison, though the nickname may not have arisen until later.

By the late 1830s, the name "Mondscheinsonate" was being used in German publications[12] and "Moonlight Sonata" in English[13] publications. Later in the nineteenth century, the sonata was universally known by that name.[14]

Many critics have objected to the subjective, romantic nature of the title "Moonlight", which has at times been called "a misleading approach to a movement with almost the character of a funeral march"[15] and "absurd".[16] Other critics have approved of the sobriquet, finding it evocative[17] or in line with their own interpretation of the work.[18] Gramophone founder Compton Mackenzie found the title "harmless", remarking that "it is silly for austere critics to work themselves up into a state of almost hysterical rage with poor Rellstab", and adding, "what these austere critics fail to grasp is that unless the general public had responded to the suggestion of moonlight in this music Rellstab's remark would long ago have been forgotten."[19] Donald Francis Tovey thought the title of Moonlight was appropriate for the first movement but not for the other two.[20]

Carl Czerny, Beethoven's pupil, described the first movement as "a ghost scene, where out of the far distance a plaintive ghostly voice sounds".[21]

Franz Liszt described the second movement as "a flower between two abysses".[8]

Form

Although no direct testimony exists as to the specific reasons why Beethoven decided to title both the Op. 27 works as Sonata quasi una fantasia, it may be significant that the layout of the present work does not follow the traditional movement arrangement in the Classical period of fast–slow–[fast]–fast. Instead, the sonata possesses an end-weighted trajectory, with the rapid music held off until the third movement. In his analysis, German critic Paul Bekker states: "The opening sonata-allegro movement gave the work a definite character from the beginning ... which succeeding movements could supplement but not change. Beethoven rebelled against this determinative quality in the first movement. He wanted a prelude, an introduction, not a proposition".[22]

The sonata consists of three movements:

- Adagio sostenuto

- Allegretto

- Presto agitato

I. Adagio sostenuto

The first movement,[c] in C♯ minor and alla breve, is written in modified sonata-allegro form.[23] Donald Francis Tovey warned players of this movement to avoid "taking [it] on a quaver standard like a slow 12

8".[20]

The movement opens with an octave in the left hand and a triplet figuration in the right. A melody that Hector Berlioz called a "lamentation",[citation needed] mostly by the left hand, is played against an accompanying ostinato triplet rhythm, simultaneously played by the right hand. The movement is played pianissimo (pp) or "very quietly", and the loudest it gets is piano (p) or "quietly".

The adagio sostenuto tempo has made a powerful impression on many listeners; for instance, Berlioz commented that it "is one of those poems that human language does not know how to qualify".[24] Beethoven's student Carl Czerny called it "a nocturnal scene, in which a mournful ghostly voice sounds from the distance".[2] The movement was very popular in Beethoven's day, to the point of exasperating the composer himself, who remarked to Czerny, "Surely I've written better things".[25][26]

In his book Beethoven's pianoforte sonatas,[27] the renowned pianist Edwin Fischer suggests that this movement of this sonata is based on Mozart's "Ah soccorso! Son tradito" of his opera Don Giovanni, which comes just after the Commendatore's murder. He claims to have found, in the archives of the Wiener Musikverein, a sketch in Beethoven's handwriting of a few lines of Mozart's music (which bears the same characteristic triplet figuration) transposed to C♯ minor, the key of the sonata. "In any case, there is no romantic moon-light in this movement: it is rather a solemn dirge", writes Fischer.

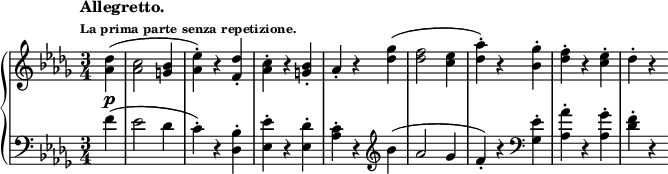

II. Allegretto

The second movement is a relatively conventional minuet in triple time, with the first section of the minuet not repeated. It is a seeming moment of relative calm written in D♭ major, the more easily notated enharmonic equivalent of C♯ major, the parallel major of the main work's key, C♯ minor. The slight majority of the movement is in piano (p), but a handful of sforzandos (sfz) and fortepianos (fp) helps to maintain the movement's cheerful disposition. It is the shortest of the movements and has been called the "less popular" interlude between the first and third movements.[28] Franz Liszt is said to have described the second movement as "a flower between two chasms".[29]

III. Presto agitato

The stormy final movement (C♯ minor), in sonata form and common time, is the weightiest of the three, reflecting an experiment of Beethoven's (also carried out in the companion sonata Opus 27, No. 1 and later on in Opus 101), namely, placement of the most important movement of the sonata last. The writing has many fast arpeggios/broken chords, strongly accented notes, and fast alberti bass sequences that fall both into the right and left hands at various times. An effective performance of this movement demands lively, skillful playing and great stamina, and is significantly more demanding technically than the 1st and 2nd movements.

Of the final movement, Charles Rosen has written "it is the most unbridled in its representation of emotion. Even today, two hundred years later, its ferocity is astonishing".[24]

Beethoven's heavy use of sforzando (sfz) notes, together with just a few strategically located fortissimo (ff) passages, creates the sense of a very powerful sound in spite of the predominance of piano (p) markings throughout.

Beethoven's pedal mark

At the opening of the first movement, Beethoven included the following direction in Italian: "Si deve suonare tutto questo pezzo delicatissimamente e senza sordino" ("This whole piece ought to be played with the utmost delicacy and without damper[s]"[30]). The way this is accomplished (both on today's pianos and on those of Beethoven's day) is to depress the sustain pedal throughout the movement – or at least to make use of the pedal throughout, but re-applying it as the harmony changes.

The modern piano has a much longer sustain time than the instruments of Beethoven's time, so that a steady application of the sustain pedal creates a dissonant sound. In contrast, performers who employ a historically based instrument (either a restored old piano or a modern instrument built on historical principles) are more able to follow Beethoven's direction literally.

For performance on the modern piano, several options have been put forth.

- One option is simply to change the sustain pedal periodically where necessary to avoid excessive dissonance. This is seen, for instance, in the editorially supplied pedal marks in the Ricordi edition of the sonata.[31]

- Half pedaling—a technique involving a partial depression of the pedal—is also often used to simulate the shorter sustain of the early nineteenth century pedal. Charles Rosen suggested either half-pedaling or releasing the pedal a fraction of a second late.[24]

- Joseph Banowetz suggests using the sostenuto pedal: the pianist should pedal cleanly while allowing sympathetic vibration of the low bass strings to provide the desired "blur". This is accomplished by silently depressing the piano's lowest bass notes before beginning the movement, then using the sostenuto pedal to hold these dampers up for the duration of the movement.[32]

Influence on later composers

The C♯ minor sonata, particularly the third movement, is held to have been the inspiration for Frédéric Chopin's Fantaisie-Impromptu, and the Fantaisie-Impromptu to have been in fact a tribute to Beethoven.[33] It manifests the key relationships of the sonata's three movements, chord structures, and even shares some passages. Ernst Oster writes: "With the aid of the Fantaisie-Impromptu we can at least recognize what particular features of the C♯ minor Sonata struck fire in Chopin. We can actually regard Chopin as our teacher as he points to the coda and says, 'Look here, this is great. Take heed of this example!' ... The Fantaisie-Impromptu is perhaps the only instance where one genius discloses to us – if only by means of a composition of his own – what he actually hears in the work of another genius."[34]

Carl Bohm's "Meditation", Op. 296, for violin and piano, adds a violin melody over the unaltered first movement of Beethoven's sonata.[35]

Dmitri Shostakovich quoted the sonata's first movement in his Viola Sonata, op. 147 (1975), his last composition. The third movement, where the quotation takes fragmentary form, is called an "Adagio in memory of Beethoven".

Notes and references

Notes

- The title page is in Italian, and reads SONATA quasi una FANTASIA per il Clavicembalo o Piano=forte composta e dedicata alla Damigella Contessa Giulietta Guicciardi da Luigi van Beethoven Opera 27 No. 2. In Vienna presso Gio. Cappi Sulla Piazza di St. Michele No. 5. (In English, "Sonata, almost a fantasia for harpsichord or pianoforte. Composed, and dedicated to Mademoiselle Countess Julie "Giulietta" Guicciardi, by Ludwig van Beethoven. Opus 27 No. 2. Published in Vienna by Giovanni Cappi, Michaelerplatz No. 5.") The suggestion that the work could be performed on the harpsichord reflected a common marketing practice of music publishers in the early 19th century (Siepmann 1998, p. 60).

- This dedication was not Beethoven's original intention, and he did not have Guicciardi in mind when writing the sonata. Thayer, in his Life of Beethoven, states that the work Beethoven originally intended to dedicate to Guicciardi was the Rondo in G, Op. 51, No. 2, but circumstances required that this be dedicated to Countess Lichnowsky. So he cast around at the last moment for a piece to dedicate to Guicciardi.[1]

- Note that Beethoven wrote "senza sordino"; see #Beethoven's pedal mark below.

References

- Thayer 1967, pp. 291, 297.

- Jones, Timothy. Beethoven, the Moonlight and other sonatas, op. 27 and op. 31. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 19, 43 and back cover.

- "Ludwig van Beethoven, Sonate für Klavier (cis-Moll) op. 27, 2 (Sonata quasi una fantasia), Cappi, 879". Beethovenhaus. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- "Quasi". Grove Music Online. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Schwarm, Betsy. "Moonlight Sonata". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Beethoven, Ludwig van (2004). Beethoven: The Man and the Artist, as Revealed in His Own Words. 1st World Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-59540-149-6.

- Lenz, Wilhelm von (1852). Beethoven et ses trois styles (in French). Vol. 1. Saint Petersburg: Matvey Bernard. p. 225. Beethoven et ses trois styles, 2 vols: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- "Beethoven Bookshelf".

- Maconie, Robin (2010). Musicologia: Musical Knowledge from Plato to John Cage. Scarecrow Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-8108-7696-5.

- Rellstab, Ludwig (1824). "Theodor. Eine musikalische Skizze". Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (in German): 274.

- "The Complete Beethoven: Day 344".

- See. e.g., Allgemeiner musikalischer Anzeiger. Vol. 9, No. 11, Tobias Haslinger, Vienna, 1837, p. 41.

- See, e.g., Ignaz Moscheles, ed. The Life of Beethoven. Henry Colburn pub., vol. II, 1841, p. 109.

- Aunt Judy's Christmas Volume. H. K. F. Gatty, ed., George Bell & Sons, London, 1879, p. 60.

- Kennedy, Michael. "Moonlight Sonata", from Oxford Dictionary of Music 2nd edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006 rev., p. 589.

- "Moonlight Sonata", from Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. J. A. Fuller Maitland (ed.), Macmillan, London, 1900, p. 360.

- Dubal, David. The Art of the Piano. Amadeus Press, 2004, p. 411.

- See, e.g., Wilkinson, Charles W. Well-known Piano Solos: How to Play Them. Theo. Presser Co., Philadelphia, 1915, p. 31.

- Mackenzie, Compton. "The Beethoven Piano Sonatas", from The Gramophone, August 1940, p. 5.

- Beethoven, Ludwig van (1932). Tovey, Donald Francis; Craxton, Harold (eds.). Complete Pianoforte Sonatas, Volume II (revised ed.). London: Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. p. 50. OCLC 53258888.

- Beethoven, Ludwig van (2015). Del Mar, Jonathan; Donat, Misha (eds.). Sonata quasi una Fantasia für Pianoforte (in English and German). Translated by Schütz, Gudula. Kassel: Bärenreiter. p. iii. ISMN 979-0-006-55799-8.

- Maynard Solomon, Beethoven (New York: Schirmer Books, 1998), p. 139

- Harding, Henry Alfred (1901). Analysis of form in Beethoven's sonatas. Borough Green: Novello. pp. 28–29.

- Rosen, Charles (2002). Beethoven's Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion. Yale University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-300-09070-3.

- Thayer, Alexander Wheelock (1967) [1921]. Elliot Forbes (ed.). Thayer's Life of Beethoven (revised ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02702-1.[page needed]

- Fishko, Sara. "Why do we love the 'Moonlight' Sonata?". NPR. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Fischer, Edwin (1959). Beethoven's Pianoforte Sonatas: A Guide for Students & Amateurs. Faber. p. 62.

- Donaldson, Bryna. "Beethoven's Moonlight Fantasy". American Music Teacher, vol. 20, no. 4, 1971, pp. 32–32. JSTOR 43533985. Accessed 20 October 2023.

- Brendel, Alfred (2001). Alfred Brendel on music. A Capella Books. p. 71. ISBN 1-55652-408-0.

- Translation from Rosenblum 1988, p. 136

- William and Gayle Cook Music Library, Indiana University School of Music Beethoven, Sonate per pianoforte, Vol. 1 (N. 1–16), Ricordi

- Banowetz, J. (1985). The Pianist's Guide to Pedaling, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 168.

- Oster 1983.

- Oster 1983, p. 207.

- Meditation, Op. 296 (Carl Bohm): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

Sources

- Rosenblum, Sandra P. (1988). Performance Practices in Classic Piano Music: Their Principles and Applications. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Oster, Ernst (1983). "The Fantaisie-Impromptu: A Tribute to Beethoven". In David Beach (ed.). Aspects of Schenkerian Analysis. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02800-3.

- Siepmann, Jeremy (1998). The Piano: The Complete Illustrated Guide to the World's Most Popular Musical Instrument.

External links

- Harding, Henry Alfred (1901). "Sonata No. 14". Analysis of Form in Beethoven's Sonatas. Borough Green Sevenoaks, Kent: Novello. pp. 28–29 – via Internet Archive.

- Analysis and recordings review of Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata, Roni's Journal, September 2007, Classical Music Blog

- Lecture by András Schiff on Beethoven's Piano Sonata Op. 27, No. 2 – via The Guardian

Scores

- Piano Sonata No. 14: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Piano Sonata No. 14 in C♯ major, Op. 27/2 (interactive score) on Verovio Humdrum Viewer

- Ricordi edition, The William and Gayle Cook Music Library at the Indiana University School of Music

![\unfoldRepeats

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff = "right" \with {

midiInstrument = "acoustic grand"

} \relative c' { \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo "Adagio sostenuto" 4 = 52

\key cis \minor

\time 2/2

\stemNeutral

\tuplet 3/2 { gis8^"Si deve suonare tutto questo pezzo delicatissimamente e senza sordino" cis e }

\override TupletNumber.stencil = ##f

\repeat unfold 7 { \tuplet 3/2 { gis,8[ cis e] } } |

\tuplet 3/2 { a,8[( cis e] } \tuplet 3/2 { a, cis e) } \tuplet 3/2 { a,8[( d! fis] } \tuplet 3/2 { a, d fis) } |

\tuplet 3/2 { gis,([ bis fis'] } \tuplet 3/2 { gis, cis e } \tuplet 3/2 { gis,[ cis dis!] } \tuplet 3/2 { fis, bis dis) } |

}

\new Staff = "left" \with {

midiInstrument = "acoustic grand"

} {

\clef bass \relative c' {

\override TextScript #'whiteout = ##t

\key cis \minor

\time 2/2

<cis,, cis'>1^\markup \italic { sempre \dynamic pp e senza sordino } \noBreak

<b b'> \noBreak

<a a'>2 <fis fis'> \noBreak

<gis gis'> <gis gis'> \noBreak

}

}

>>

\midi { }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/0/20gtgyj7mwlaj2dw38jzw41rsbxlas3/20gtgyj7.png)

![\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff = "right" \with {

midiInstrument = "acoustic grand"

} \relative c'' { \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo "Presto agitato" 4=160

\key cis \minor

\time 4/4

%1

s2\p cis,16 e, \[ gis cis e gis, cis e \] \bar ".|:"

gis cis, e gis cis e, \[ gis cis e gis, cis e \] <gis, cis e gis>8\sfz-. <gis cis e gis>-.

%2

s2. dis16 gis, bis dis

%3

gis bis, dis gis bis dis, gis bis dis gis, bis dis <gis, bis dis gis>8-.\sfz <gis bis dis gis>-.

}

\new Staff = "left" \with {

midiInstrument = "acoustic grand"

} {

\clef bass \relative c' {

\key cis \minor

\time 4/4

\tempo "Presto agitato."

% impossible d'afficher le premier !

%1

<< { \[ r16 gis,16 cis e \] gis16 cis, e gis s2 } \\ { cis,,8-. gis'-. cis,-. gis'-. cis,-. gis'-. cis,-. gis'-.}>> \stemDown \bar ".|:"

%2

cis, gis' cis, gis' cis, gis' <cis, cis'>\sfz gis'

%3

<<{r16 gis bis dis gis bis, dis gis bis dis, gis bis s4}\\{bis,,8 gis' bis, gis' bis, gis' bis, gis'}>>

bis, gis' bis, gis' bis, gis' <bis, bis'>\sfz gis'

}

}

>>

\midi { }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/5/n51c3kajykdtzkce4mft3genwyi6zkw/n51c3kaj.png)