|

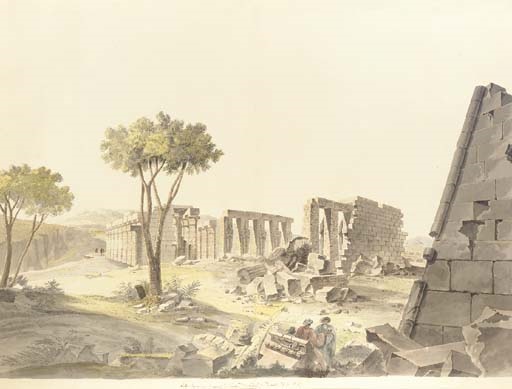

| The ruins of the Ramesseum, known as the tomb of Ozymandias, at Thebes, Egypt; watercolor by Charles-Louis Balzac |

Ozymandias

by Percy Bysshe Shelley

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: "Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away."

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

* * * * * * *

The Memory of Ruins

by R.E. Slater

“Man is of soul and body, formed for deeds

Of high resolve; yet doomed to pass away.”

- Queen Mab

What is man... once illusion is removed?

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

in solemn indifference across its endless reaches.

Patient as the stars, silent as death, loveless and cold,

concealing fraught recesses in ancient, molded stone.

Telling of the dying works of striving, mortal man -

Telling of the dying works of striving, mortal man -

imperious to time and space, standing as gods.

All kings have passed; all boasts have lost their tongues,

before an unflinching sun in golden orb uplifted.

Blazing in peerless power across its hot dominion,

before an unflinching sun in golden orb uplifted.

Blazing in peerless power across its hot dominion,

whose sand and stone once sustained mighty empires.

Ah, what is mortal man but dream and shadow -

a vapor fed in yesterday's light, lasting but a day.

Ah, what is mortal man but dream and shadow -

a vapor fed in yesterday's light, lasting but a day.

So lies an empire's ruins like names beneath the sand,

their works silenced in the patient wearing of long years.

No earthly throne can survive the grinding work of wind,

nor jeweled crown outlive the slow moil of the worm.

What had commanded worlds no longer utters decrees,

their works silenced in the patient wearing of long years.

No earthly throne can survive the grinding work of wind,

nor jeweled crown outlive the slow moil of the worm.

What had commanded worlds no longer utters decrees,

nor passing reign could outlast time's steady erosions.

From sculptor’s mind and hand endures but a trace -

a proud sneer, soulless eyes, surveying vanished realms.

All empires are fleeting memories lifted in haughty eyes,

All empires are fleeting memories lifted in haughty eyes,

their gathered power fading, testament to borrowed days.

For time unmakes the mighty in its unhurried pace,

For time unmakes the mighty in its unhurried pace,

and muted ruins lie lonely, lost and misremembered.

R.E. Slater

January 14, 2026

@copyright R.E. Slater Publications

all rights reserved

Ozymandias - Smith initially titled his poem the same as Shelley’s; later, he re-titled it “On a Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below.” He was a friend of Shelley's and helped to manage his finances.

IN Egypt's sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Deseart knows:

"I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone,

"The King of Kings; this mighty City shows

"The wonders of my hand." - The City's gone,

Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder, and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro' the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

"Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert." Such is the fleeting nature of power and the inevitable decay of human accomplishments over time. Upon looking, the statute's pedestal was inscribed, "My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!" And so we do, seeing the desolate rubble and ruins that lie all about the sand and stone. - R.E. Slater

What is the main idea of the poem "Ozymandias"?

by Gretchen Mussey, enotes

In the poem, Shelley describes the ruins of a once great statue of a sphinx intended to represent the almighty reign of Ramses II, also known as Ozymandias. However, instead of witnessing the powerful image of an omnipotent ruler, all that remains of Ozymandias's statue is a "Half sunk," broken image of a domineering man that is decaying in the sand. Ironically, Ramses's original intentions of his statue have the opposite effect on travelers, who only witness how time impacts one's legacy and accomplishments. Shelley's poem examines the transitory nature of life, legacy, power, and government institutions. The decaying, broken image of Ozymandias's visage portrays how time destroys every human accomplishment. The inscription on the bottom of the statue is also ironic and symbolically represents how one's pursuit of power and glory are illusory and fleeting.

* * * * * * *

What kind of person is Ozymandias as he is depicted in Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem of the same name?

by Andrew Nightengale, enotes

We learn something about Ozymandias from line three of the poem. These lines provide a description of the individual whose image has been sculpted in stone, which now lies broken in the sand.

Near them, on the sand,Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command...

The words in bold inform us that the sculpture expresses a frown which suggests a serious expression; 'wrinkled lip' informs of a haughty expression, possessed by one who regards others with contempt. This is further supported and accentuated by the word 'sneer', which tells us that the person so depicted had disdain for those whom he commanded. The fact that his command is described as 'cold' suggests that he was heartless and cruel. Our perception is therefore of a cruel, hard, ruthless taskmaster who led without any love for his subjects. We can therefore rightly assume that he must have been either a dictator or tyrant.

The speaker tells us that the sculptor 'well those passions read,' which is an indication that the skilled artist was not remiss in the manner in which he portrayed his subject in this now decayed work. The line "The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed" further informs us that Ozymandias saw his subjects as buffoons and treated them as if they were idiots. He relished abusing his subjects and he fed his overblown ego by treating them with utter disregard and making fools of them.

Further insight is provided into Ozymandias' unpleasant superciliousness in the lines:

And on the pedestal these words appear:‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

So vain and egotistical was he that he expressed his greatness on the pedestal of his statue, stating that he was greater than any ruler. Even the mightiest of the mighty could not challenge his glory for he was so all-powerful and great that all any other ruler could do was to become disparaged when they witnessed his magnitude and magnificence.

It is therefore ironic that all that has remained of Ozymandias' so-called prodigious power is a broken statue, enveloped by the sands of the desert.

Nothing beside remains

Ozymandias has been defeated by death and time. The lonely, open and vast desert has become his final resting place, leaving a poor testament to his once, as he believed, incomparable might.

* * * * * * *

Ozymandias

"Ozymandias" (/ˌɒziˈmændiəs/ oz-ee-MAN-dee-əs)[1] is the title of two related sonnets published in 1818. The first was written by the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) and was published in the 11 January 1818 issue of The Examiner[2] of London. The poem was included the following year in Shelley's collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems,[3] and in a posthumous compilation of his poems published in 1826.[4] Shelley's most famous work, "Ozymandias" is frequently anthologised.

Shelley wrote the poem in friendly competition with his friend and fellow poet Horace Smith (1779–1849), who also wrote a sonnet on the same topic with the same title. Smith's poem was published in The Examiner three weeks after Shelley's, on February 1st, 1818. Both poems explore the fate of history and the ravages of time: even the greatest men and the empires they forge are impermanent, their legacies fated to decay into oblivion.

In antiquity, Ozymandias (Ὀσυμανδύας) was a Greek name for the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II. Shelley began writing his poem in 1817, soon after the British Museum's announcement that they had acquired a large fragment of a statue of Ramesses II from the 13th century BCE; some scholars believe Shelley was inspired by the acquisition. The 7.25-short-ton (6.58 t; 6,580 kg) fragment of the statue's head and torso had been removed in 1816 from the mortuary temple of Ramesses (the Ramesseum) at Thebes by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Battista Belzoni. It had been expected to arrive in London in 1818, but did not arrive until 1821.[5][6]

Writing and publication history

The banker and political writer Horace Smith spent the Christmas season of 1817–1818 with Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Shelley. At this time, members of Shelley's literary circle would sometimes challenge each other to write competing sonnets on a common subject: Shelley, John Keats and Leigh Hunt wrote competing sonnets on the Nile around the same time. Shelley and Smith both chose a passage from the writings of the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, which described a massive Egyptian statue and quoted its inscription: "King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work." In the poem Diodorus becomes "a traveller from an antique land."[7]

The two poems were later published in Leigh Hunt's The Examiner,[2] published by Leigh's brother John Hunt in London. Hunt had already been planning to publish a long excerpt from Shelley's new epic, The Revolt of Islam, later the same month.

Shelley's poem

Shelley's poem was published on 11 January 1818 under the pen name Glirastes. It appeared on page 24 in the yearly collection, under Original Poetry. Shelley's poem was later republished under the title "Sonnet. Ozymandias" in his 1819 collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems by Charles and James Ollier[3] and in the 1826 Miscellaneous and Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley by William Benbow, both in London.[4]

Smith's poem

Smith's poem was published, along with a note signed with the initials H.S., on 1 February 1818.[8] It takes the same subject, tells the same story, and makes a similar moral point, but one related more directly to modernity, ending by imagining a hunter of the future looking in wonder on the ruins of a forgotten London. It was originally published under the same title as Shelley's verse; but in later collections Smith retitled it "On A Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below".[9]

Comparison of the two poems

Percy Shelley's "Ozymandias"I met a traveller from an antique landWho said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stoneStand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,Tell that its sculptor well those passions readWhich yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:And on the pedestal these words appear:'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'Nothing beside remains. Round the decayOf that colossal wreck, boundless and bareThe lone and level sands stretch far away.[4]

Horace Smith's "Ozymandias"In Egypt's sandy silence, all alone,Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throwsThe only shadow that the Desert knows:—"I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone,"The King of Kings; this mighty City showsThe wonders of my hand."— The City's gone,—Naught but the Leg remaining to discloseThe site of this forgotten Babylon.We wonder,—and some Hunter may expressWonder like ours, when thro' the wildernessWhere London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guessWhat powerful but unrecorded raceOnce dwelt in that annihilated place.[10]

Analysis and interpretation

Form

Shelley's "Ozymandias" is a sonnet, written in iambic pentameter, but with an atypical rhyme scheme (ABABA CDCEDEFEF) when compared to other English-language sonnets, and without the characteristic octave-and-sestet structure.[citation needed]

Hubris

A central theme of the "Ozymandias" poems is the inevitable decline of rulers with their pretensions to greatness.[11] The name "Ozymandias" is a rendering in Greek of a part of Ramesses II's throne name, User-maat-re Setep-en-re. The poems paraphrase the inscription on the base of the statue, given by Diodorus Siculus in his Bibliotheca historica as:

Although the poems were written and published before the statue arrived in Britain,[6] they may have been inspired by the impending arrival in London in 1821 of a colossal statue of Ramesses II, acquired for the British Museum by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni in 1816.[15] The statue's repute in Western Europe preceded its actual arrival in Britain, and Napoleon, who at the time of the two poems was imprisoned on St Helena (although the impact of his own rise and fall was still fresh), had previously made an unsuccessful attempt to acquire it for France.