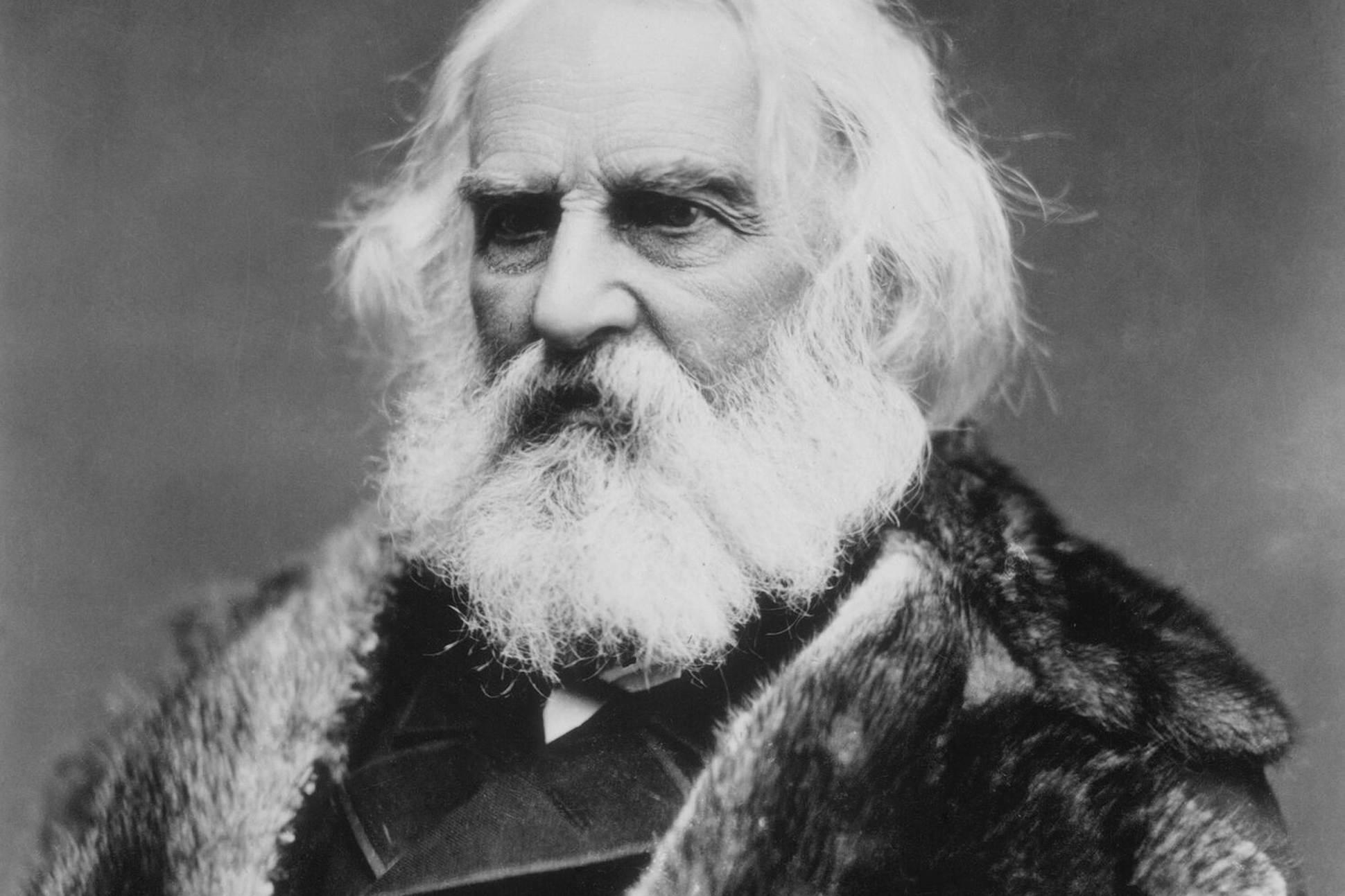

The Children’s Hour by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

by Andrew Walker, Andrew

If you’ve ever tried to convey a sarcastic remark through a written medium, you probably already know how difficult it can be to convey tone through text. For poets, this can be a very difficult mechanic to employ, but a very powerful one at the same time — not because poets are sarcastic people, but because of how useful it can be to play with connotations and denotations and take advantage of a reader’s predispositions. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow proves himself, again and again, to be very adept at using tone to enhance the messages within his poem, and The Children’s Hour is an excellent example of his use of the tool to convey the idea of his titular phenomenon.

The Children’s Hour Analysis

Between the dark and the daylight,

When the night is beginning to lower,

Comes a pause in the day’s occupations,

That is known as the Children’s Hour.

–

I hear in the chamber above me

The patter of little feet,

The sound of a door that is opened,

And voices soft and sweet.

The Children’s Hour is written very lyrically, using the same rhythm and rhyming structure from beginning to end, without any kind of emphatic break or pause. The rhyme and flow helps the poem to pick up an easygoing kind of atmosphere — poems just sound nicer when they can essentially be sung. The first verse is also crucial in establishing atmosphere, and this seems to be its only read purpose. The grammatical structure of the verse is what is most interesting, specifically that there is no subject, and the entire verse is written in passive voice. It talks about a time and talks about a name, but gives no story or purpose to either; whose occupations are paused? Who calls this the Children’s Hour? Whose children are they? None of this is established, which makes the information presented sound just a little cryptic, and a lot like fact. It’s meant to be intriguing and disarming, and largely succeeds.

The second verse, on the other hand, has a narrator, who describes the early events of the Children’s Hour for the reader. The meaning of the verse is straightforward enough — the speaker can hear light footsteps and voices from people leaving the room above. Longfellow’s word choice is interesting though — he describes the “patter” and the “soft and sweet” voices, words typical of describing children, and he also describes their room as a “chamber,” which is more typical of a castle hall or dungeon than a nursery. The word is completely unneeded from a structural standpoint — “room” would have fit just as easily, if not more, since it would have made the line the same number of syllables as the first line of the previous verse. “Chamber” holds conflicting connotation with the rest of the verse, and this makes it what is likely a very intentional choice by the author.

From my study I see in the lamplight,

Descending the broad hall stair,

Grave Alice, and laughing Allegra,

And Edith with golden hair.

–

A whisper, and then a silence:

Yet I know by their merry eyes

They are plotting and planning together

To take me by surprise.

The second and third verses describe the children arriving to the speaker’s study, and they follow a similar structure in tone to the verses before them. Allegra is laughing, Edith is golden, and Alice is grave, and that last adjective is a truly odd one to find in the bunch. The children’s eyes are merry, yet they are plotting. What is interesting here is that these changes in description, these words that don’t belong, do not detract from the cheerful atmosphere; rather, the reader tries to imagine the words has having other meanings. It makes more sense to think that Alice is simply taking the plan very seriously than it does to imagine one of these children as being cold and serious. This is a triumph of The Children’s Hour’s tonal developments so early in the work.*

A sudden rush from the stairway,

A sudden raid from the hall!

By three doors left unguarded

They enter my castle wall!

–

They climb up into my turret

O’er the arms and back of my chair;

If I try to escape, they surround me;

They seem to be everywhere.

At this point in the poem, it’s fairly clear that the speaker’s children are the subjects of the work, so when Longfellow continues to describe their embrace as a fortress raid, the idea becomes endearing, rather than threatening. The tone of the work is influencing the reader’s perceived meaning of each word — so here, he uses many more words that might otherwise be considered dark additions to a story, such as “rush,” “raid,” “unguarded,” “wall,” “turret,” “escape,” and “surround.” There are a lot of them! But in this context, it’s more cute than threatening, and it seems that he may be describing events as they take place in the children’s minds, rather than the speaker’s own. It makes sense to think of young kids as imagining that they are invading a castle, and that the study chair is an outpost, with their parent as the object of a daring raid. In this context, the poem feels even more fun than previously.

They almost devour me with kisses,

Their arms about me entwine,

Till I think of the Bishop of Bingen

In his Mouse-Tower on the Rhine!

–

Do you think, o blue-eyed banditti,

Because you have scaled the wall,

Such an old moustache as I am

Is not a match for you all!

After the children reach the study chair, the speaker begins to imagine themselves as a part of the children’s story. The reference to the Bishop of Bingen is somewhat obscure — in popular medieval legend, he was a cruel and unfair leader who’s tower was invaded by rats as punishment for a famine he did little to avoid or help his subjects through. The speaker, however, feels more confident than the Bishop, and warns his children that reaching the tower was the easy part and that there is one guard they cannot get past, namely their own father (judging from the self-described “old moustache”). He places himself within the story and calls them “banditti,” a group of outlaws befitting of their narrative.

I have you fast in my fortress,

And will not let you depart,

But put you down into the dungeon

In the round-tower of my heart.

–

And there will I keep you forever,

Yes, forever and a day,

Till the walls shall crumble to ruin,

And moulder in dust away!

Tonally, The Children’s Hour is much benefitted when the father of the children embraces their narrative, and the story in the final four verses becomes about embracing that story and making it a part of the poem itself. Of course, because this is the Children’s Hour, the father will not allow his children to leave the “fortress,” returning their affection and promising to love them forever, still using their own story as his means of doing so — the “round-tower of my heart” is a somewhat literal metaphor, but it works here. The image of the tower crumbling to dust is a sad image to end off the poem, because it more than likely symbolizes the death of the father, who is saying that not a day will go by in his life that he will not love his children. It is a very sweet adaptation of the love a father has for his children, which is almost certainly the inspiration of the poem. Alice, Edith, and Anne Allegra Longfellow are the name of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s first three children, a fact which makes the playful and childish narrative of The Children’s Hour much, much sweeter to contemplate.

* * * * * * *