He told me the truth about the femme fatale,

which freed my knowledge to sit about in the light of day,

like an object,

to be coped with,

not hid like some hair monster.

And I didn’t die.

- SP

* * * * * * * * * * *

A New Chapter of Grief in Plath-Hughes Legacy

April 11, 2009

FAIRBANKS, Alaska — Before his death in 1998, the English poet Ted Hughes published a searing volume about his life with Sylvia Plath called “Birthday Letters.” The poems, almost all addressed to Ms. Plath, explored the beauty and then fracturing of their marriage before her suicide in 1963.

One poem, though, was written to their children, Frieda and Nicholas. Titled “The Dogs Are Eating Your Mother,” it warned of ravenous Plath devotees who “will find you every bit as succulent,” and it offered a kind of blessing to Nicholas, who had long kept the literati at bay:

The lines were a succinct rendering of Nicholas Hughes, a man who joyously devoted his career to the study of fish in Alaska’s snowy rivers and whose home, a handsome 2,800-square-foot cabin on 20 pristine acres of spruce and birch, faced toward the distant Brooks Range. He was a man who made it clear to friends that he would rather discuss the finer points of ice fishing than the writings of his parents. Indeed, some of his colleagues in the School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, worked with him for years without knowing he was the son of two major 20th-century poets.

All that changed on March 16.

It was sunny, the temperature hovering just below zero, and Mr. Hughes seemed in good spirits. For years he had battled depression, as his mother had, and on a recent trip to New Zealand he had even talked of suicide. But he had endured other low periods, leaning on close friends, getting medical help and managing his illness with exercise and regular winter migrations to New Zealand’s sunnier climes. At his cabin that afternoon, he drank tea with his girlfriend, Christine M. Hunter.

“It’s a good day,” he told her. He said he was going to go for a walk. Ms. Hunter, a wildlife ecology professor at the university, went upstairs to grade papers. Around 4 p.m., when he had not returned, Ms. Hunter went searching. Mr. Hughes had told friends that if he was ever going to take his life, he had decided the best method was to hang himself in his workshop by his cabin. Ms. Hunter found him there, hanging by a thin nylon cord tied to an exposed ceiling beam.

Mr. Hughes, 47, did not leave a note. Investigators, though, said it was clear from the evidence that he had planned his death carefully. “He knew what he was doing,” State Trooper Michael Wery said.

In the weeks since, the news of the suicide has cut through two distant and disconnected worlds in vastly different ways.

One poem, though, was written to their children, Frieda and Nicholas. Titled “The Dogs Are Eating Your Mother,” it warned of ravenous Plath devotees who “will find you every bit as succulent,” and it offered a kind of blessing to Nicholas, who had long kept the literati at bay:

So leave her.

Let her be their spoils. Go wrap

Your head in the snowy rivers

of the Brooks Range.

The lines were a succinct rendering of Nicholas Hughes, a man who joyously devoted his career to the study of fish in Alaska’s snowy rivers and whose home, a handsome 2,800-square-foot cabin on 20 pristine acres of spruce and birch, faced toward the distant Brooks Range. He was a man who made it clear to friends that he would rather discuss the finer points of ice fishing than the writings of his parents. Indeed, some of his colleagues in the School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, worked with him for years without knowing he was the son of two major 20th-century poets.

All that changed on March 16.

It was sunny, the temperature hovering just below zero, and Mr. Hughes seemed in good spirits. For years he had battled depression, as his mother had, and on a recent trip to New Zealand he had even talked of suicide. But he had endured other low periods, leaning on close friends, getting medical help and managing his illness with exercise and regular winter migrations to New Zealand’s sunnier climes. At his cabin that afternoon, he drank tea with his girlfriend, Christine M. Hunter.

“It’s a good day,” he told her. He said he was going to go for a walk. Ms. Hunter, a wildlife ecology professor at the university, went upstairs to grade papers. Around 4 p.m., when he had not returned, Ms. Hunter went searching. Mr. Hughes had told friends that if he was ever going to take his life, he had decided the best method was to hang himself in his workshop by his cabin. Ms. Hunter found him there, hanging by a thin nylon cord tied to an exposed ceiling beam.

Mr. Hughes, 47, did not leave a note. Investigators, though, said it was clear from the evidence that he had planned his death carefully. “He knew what he was doing,” State Trooper Michael Wery said.

In the weeks since, the news of the suicide has cut through two distant and disconnected worlds in vastly different ways.

In the thriving community of Plath and Hughes scholars, the death has been deeply felt through the prism of his parents’ writings. His birth was vividly chronicled in Ms. Plath’s journals. He was “the baby in the barn” in “Nick and the Candlestick,” from Ms. Plath’s best-known collection, “Ariel,” written in her final months.

And in the event that looms over every page of “Birthday Letters,” he was little Nick, barely 1, when Ms. Plath carefully sealed him and Frieda in another room and then gassed herself in the oven of her North London flat.

“They almost feel like they know them through the poetry,” said Karen V. Kukil, who curates the Sylvia Plath collection at Smith College. Ms. Kukil said that when she gave talks, people inevitably asked about Nicholas and Frieda. After all, not only did they absorb their mother’s death, but they also endured what came six years later, when Assia Wevill, the woman for whom Mr. Hughes left Ms. Plath, gassed herself and their 4-year-old half sister, Shura.Photo

And in the event that looms over every page of “Birthday Letters,” he was little Nick, barely 1, when Ms. Plath carefully sealed him and Frieda in another room and then gassed herself in the oven of her North London flat.

“They almost feel like they know them through the poetry,” said Karen V. Kukil, who curates the Sylvia Plath collection at Smith College. Ms. Kukil said that when she gave talks, people inevitably asked about Nicholas and Frieda. After all, not only did they absorb their mother’s death, but they also endured what came six years later, when Assia Wevill, the woman for whom Mr. Hughes left Ms. Plath, gassed herself and their 4-year-old half sister, Shura.Photo

|

| Nicholas Hughes | Credit Courtesy of Mark Wipfli |

Audiences, Ms. Kukil said, seemed reassured when she described Nicholas Hughes’s life in remote Alaska, a path in keeping with his father’s love of nature and fishing. His suicide, she said, “really hit people hard.”

In Fairbanks, the responses are more complex. Here a community of scientists knew him not through his parents’ poetry, but through the ingenuity of his research into freshwater ecosystems. They knew him from ice fishing and cycling, from gardening or making pottery. And with his death there is building resentment, a sense that his life and death are being distorted by strangers, depicted as either the inevitable after-effect of his father’s infidelities or somehow genetically foreordained by his mother’s demons.

Their Nicholas Hughes was a man of immense energy and curiosity, most at home in a well-worn wool sweater and a battered pair of Xtratuf boots, marching over tundra toward some hidden bend of water. He was possessed with an utter distaste for academic politics and a special gift for finding simple solutions to complex scientific problems, which he then translated into clear, clean prose for the most important publications in his field.

“For me, his work was elegant and beautiful, just like a good poem,” said Amanda E. Rosenberger, an assistant professor in the School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, wiping away tears.

His friends here are grappling with his death not as heart-rending literary coda, but as devastating loss — for his girlfriend, for the students he mentored and for the future of fish ecology. Using elaborate underwater camera systems and sophisticated computer models, Mr. Hughes had developed new ideas about how salmon, grayling and other fish chose their habitats. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of ecosystems, yet he was also an expert in hydrodynamics and evolutionary biology — a kind of academic triple threat.

This is one reason people here scoff at the notion that he came to Alaska as some kind of “Into the Wild” escape. His fascination with fish spans more than two decades, back to Oxford University, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in zoology, followed by a Ph.D. in biology from the university here in 1991. After winning several prestigious research positions in Canada and Alaska, he was hired as an assistant professor here in 1998. He was 36, and a promotion to associate professor and tenure followed in due course.

Mr. Hughes worked in a cluster of research buildings atop a ridge overlooking a plain where herds of reindeer graze. It is an informal setting, where scientists keep cross-country skis in their laboratories so they can go skiing at lunchtime. The life suited him, both professionally and because of his love for the Alaskan wilderness. As much as he liked observing fish, he also loved to catch them, especially the homely but tasty burbot.

“He was fully engaged in the Alaska experience,” said Denis A. Wiesenburg, dean of the School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences.

But he also appreciated another quality of Alaska — the shared reverence for being left alone. Several of his friends politely refused interview requests, saying they simply did not believe that Mr. Hughes would want any intrusion into his privacy. Likewise, those who knew of his family story considered it basic good manners not to trespass on the subject uninvited.

In Fairbanks, the responses are more complex. Here a community of scientists knew him not through his parents’ poetry, but through the ingenuity of his research into freshwater ecosystems. They knew him from ice fishing and cycling, from gardening or making pottery. And with his death there is building resentment, a sense that his life and death are being distorted by strangers, depicted as either the inevitable after-effect of his father’s infidelities or somehow genetically foreordained by his mother’s demons.

Their Nicholas Hughes was a man of immense energy and curiosity, most at home in a well-worn wool sweater and a battered pair of Xtratuf boots, marching over tundra toward some hidden bend of water. He was possessed with an utter distaste for academic politics and a special gift for finding simple solutions to complex scientific problems, which he then translated into clear, clean prose for the most important publications in his field.

“For me, his work was elegant and beautiful, just like a good poem,” said Amanda E. Rosenberger, an assistant professor in the School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, wiping away tears.

His friends here are grappling with his death not as heart-rending literary coda, but as devastating loss — for his girlfriend, for the students he mentored and for the future of fish ecology. Using elaborate underwater camera systems and sophisticated computer models, Mr. Hughes had developed new ideas about how salmon, grayling and other fish chose their habitats. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of ecosystems, yet he was also an expert in hydrodynamics and evolutionary biology — a kind of academic triple threat.

This is one reason people here scoff at the notion that he came to Alaska as some kind of “Into the Wild” escape. His fascination with fish spans more than two decades, back to Oxford University, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in zoology, followed by a Ph.D. in biology from the university here in 1991. After winning several prestigious research positions in Canada and Alaska, he was hired as an assistant professor here in 1998. He was 36, and a promotion to associate professor and tenure followed in due course.

Mr. Hughes worked in a cluster of research buildings atop a ridge overlooking a plain where herds of reindeer graze. It is an informal setting, where scientists keep cross-country skis in their laboratories so they can go skiing at lunchtime. The life suited him, both professionally and because of his love for the Alaskan wilderness. As much as he liked observing fish, he also loved to catch them, especially the homely but tasty burbot.

“He was fully engaged in the Alaska experience,” said Denis A. Wiesenburg, dean of the School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences.

But he also appreciated another quality of Alaska — the shared reverence for being left alone. Several of his friends politely refused interview requests, saying they simply did not believe that Mr. Hughes would want any intrusion into his privacy. Likewise, those who knew of his family story considered it basic good manners not to trespass on the subject uninvited.

|

| Some of Nicholas Hughes’s colleagues went years without knowing that he was the son of the poets Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, above. | Credit Agence France-Presse, Associated Press |

Frank Soos, a retired English professor, was in a cycling group with Mr. Hughes, and he knew the work of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes well. But not once did he broach the subject. “It was so apparent he didn’t want to go there,” Mr. Soos said. In fact, he recalled, their relationship changed when Mr. Hughes learned he taught English.

“You could feel a palpable distance creep in there,” he said.

Carin Bailey Stephens, a public information officer at the university, had studied poetry and knew about his parents through the grapevine. “I hear you are the son of Sylvia Plath,” she recalled telling him, hoping for a conversation about writing.

“He just immediately made it clear that he knew about science and he wasn’t interested in writing,” she said. “He was very gentle about it.”

His colleagues knew of his struggle with depression, but they also said he worked hard to manage it. Still, in September 2006 his bosses grew alarmed when he did not show up for work for several days. Eventually the state police were asked to check up on him.

A few months later he abruptly resigned his university position. Friends said he wanted to escape the stresses of academic politics and administrative drudge work. But thanks to his mother’s literary estate, he could afford to pursue his research on his own, and he continued work with another professor, Mark S. Wipfli, on a major project studying the demographics and ecology of Chinook salmon in the Chena River.

He also bought his cabin on the outskirts of Fairbanks, and he began dating Ms. Hunter, whose own research has helped describe how global warmingis threatening polar bears. Ms. Rosenberger joined the couple for dinner in December, just before they left for New Zealand. “I was glad to see he was in a relationship and happy,” she said.

But Trooper Wery said Ms. Hunter told investigators that Mr. Hughes had become distressed about one particular subject — discord between his sister and their stepmother, Carol Hughes. The two women have quarreled in recent years over the estate of Ted Hughes. Neither Ms. Hunter nor Frieda Hughes, herself a poet, painter and author in England, responded to requests for comment.

On March 30, friends gathered in a conference room at the university for a memorial service. Colleagues from Juneau and New Zealand were patched in by video. Plans were hatched to establish the Nick Hughes Memorial Scholarship Fund at the university. Although his death generated headlines around the world, his memorial service went unmentioned in the next morning’s Daily News-Miner.

Not that the newspaper did not know about it. Dermot Cole, the newspaper’s main columnist, said he had known for at least a decade that the son of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes lived in town. Every so often he would call and try to persuade Mr. Hughes to let him write about him. “He just didn’t want to do it,” Mr. Cole said. After the suicide, he wrote Mr. Hughes’s obituary, but he said it simply did not feel right to intrude on the memorial service.

Mr. Cole said he wanted to give him his privacy.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

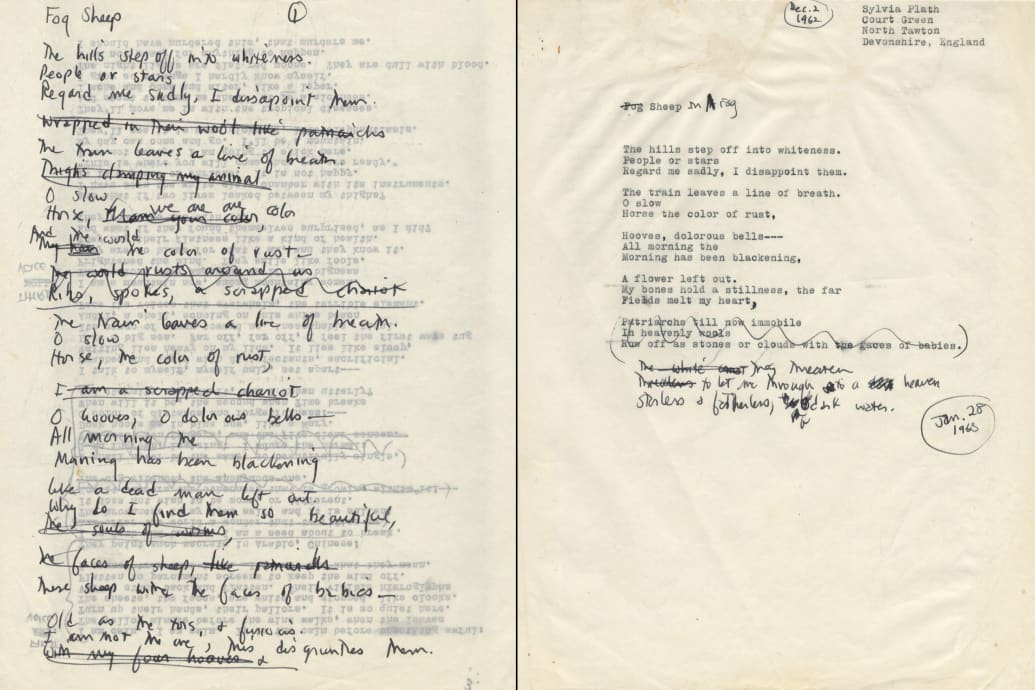

| Sylvia Plath, 1954 | Credit Everett Collection, via Alamy |

Sylvia Plath’s Last Letters Show Her Struggling

to Imagine Life Without Ted Hughes

by Katie Roiphe

Nov. 8, 2018

THE LETTERS OF SYLVIA PLATH

Volume 2: 1956-1963

Edited by Peter K. Steinberg and Karen V. Kukil

Illustrated. 1,025 pp. HarperCollins Publishers. $45.

One could certainly be forgiven for thinking that no remaining bit of Sylvia Plath scholarship could change one’s view of the much analyzed poet. However, the adroitly edited new collection of her letters, “The Letters of Sylvia Plath, Volume 2: 1956-1963,” which spans her entire marriage to the English poet Ted Hughes and its aftermath, and includes many letters that had not previously been published, provides one of the most vivid and intimate accounts of her life to date.

Volume 2: 1956-1963

Edited by Peter K. Steinberg and Karen V. Kukil

Illustrated. 1,025 pp. HarperCollins Publishers. $45.

One could certainly be forgiven for thinking that no remaining bit of Sylvia Plath scholarship could change one’s view of the much analyzed poet. However, the adroitly edited new collection of her letters, “The Letters of Sylvia Plath, Volume 2: 1956-1963,” which spans her entire marriage to the English poet Ted Hughes and its aftermath, and includes many letters that had not previously been published, provides one of the most vivid and intimate accounts of her life to date.

In particular, these letters vastly enrich our understanding of Plath’s state of mind leading up to her suicide, which has been patchy and sparse, in part because of Hughes’s decision to destroy her final journal. “The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath” ends in early July 1962, right before the ultimate crisis in their marriage, so the new collection of letters offers a fresh look at her struggle with Hughes and the last wild months of her life.

One striking aspect of these letters is how prominently and enthusiastically the domestic details of Plath’s life in England, like stew recipes or flaky crusts or home-sewn baby clothes, are discussed, even as she remains intensely dedicated to her work. She is invested in a vision of a domestic bohemian idyll with more than the usual amount of urgency. She seems to feel that this fantasy household is almost within her reach if only she could have Toll House chocolate morsels, or paint the floors, or get a sewing machine, or learn how to make her own mayonnaise. There is something feverish in this pursuit of perfection; Plath is obsessive, driven — ambitious, almost — toward domestic happiness. For nearly 800 pages, she is basically silent on any conflict with Hughes, but after hundreds of letters delineating domestic improvements and yearnings, one begins to suspect that there is a bigger problem in her house that she is trying to fix, a more profound anxiety she is trying to quiet.

|

| Plath with her mother and two children in Devon, England, 1962 | Credit CSU Archive/Everett, via Alamy |

The most substantive revelations here, however, are the letters she wrote in the last eight months of her life to an American psychiatrist, Dr. Ruth Beuscher. She began her treatment with Beuscher in 1953, after the early suicide attempt chronicled in her novel “The Bell Jar,” and saw her again five years later, when Plath and Hughes had temporarily decamped to America. The poet remained close to Beuscher until the end of her life. These desperate letters, which until recently were privately held, provide astonishing insight into Plath’s inner state in the troubled months when she wrote her strongest poems.

These letters are more intimate, more raw, than the rest of her correspondence. To other people, even her mother, with whom she had an extremely close if tortured relationship, she carefully curates herself. In her letters to Beuscher, there is a kind of frantic rush of honesty, a thought process laid bare, a concerted effort to sort through and analyze her feelings. While she is writing to other people about doll prams or pork sandwiches, she is confiding in Beuscher about Hughes disappearing after a romantic night at an expensive hotel, or frankly describing the precise tenor of their sexual relations.

Without much comment, she briefly mentions a disturbing incident in which Hughes “beat me up physically” in the days before a miscarriage. She says that at the time she felt this was an “aberration” that she had provoked by deliberately ripping a manuscript of his.

Plath apparently wanted to view these letters as therapeutic “sessions” and offered to pay Beuscher to read and respond to them, but the psychiatrist refused payment and wrote back to her anyway. In confiding in Beuscher, after discovering her husband’s affair with Assia Wevill, Plath seems to be trying to solve the problem of herself. How can she change to make the marriage work? She writes: “How can I make these women unnecessary to him? And keep up my own sense of seductiveness and womanly power? I don’t want to be sorrowful or bitter, men hate that, but what can I do in the face of these prospects?” She also writes: “Can you suggest a gracious procedure when you see some little (whoops, not little, big!) tart is after your husband at a party, or dinner or something? Do you leave them to it? Engage a hotel room? Smile & vanish? Smile & stand by? What I don’t want to be is stern & disapproving or teary. But I am only human. I have to feel I have some ground-rights.”

Plath apparently wanted to view these letters as therapeutic “sessions” and offered to pay Beuscher to read and respond to them, but the psychiatrist refused payment and wrote back to her anyway. In confiding in Beuscher, after discovering her husband’s affair with Assia Wevill, Plath seems to be trying to solve the problem of herself. How can she change to make the marriage work? She writes: “How can I make these women unnecessary to him? And keep up my own sense of seductiveness and womanly power? I don’t want to be sorrowful or bitter, men hate that, but what can I do in the face of these prospects?” She also writes: “Can you suggest a gracious procedure when you see some little (whoops, not little, big!) tart is after your husband at a party, or dinner or something? Do you leave them to it? Engage a hotel room? Smile & vanish? Smile & stand by? What I don’t want to be is stern & disapproving or teary. But I am only human. I have to feel I have some ground-rights.”

This is very far from the familiar cold rage of the late poems: “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.” The Plath of these letters is engaged in a painful struggle to make her marriage work, and, later, to finding her way to managing on her own. She reveals herself as hurt and humiliated and devastated in characteristically electric prose: “He told me the truth about the femme fatale, which freed my knowledge to sit about in the light of day, like an object, to be coped with, not hid like some hair monster. And I didn’t die.”

The letters to Beuscher are moving and revelatory because they add a dimension to the hard, brilliant, glittering fury of the late poems. We are familiar with Plath’s fierceness, the power of her imagination to exact revenge, to correct humiliations, to create dark drama out of despair. But we are notably less familiar with the Plath of these letters, trying so hard to steady herself, to gain perspective, to find her way toward the independence and health she could so clearly make out, just in the distance.

The decline of her marriage and her subsequent breakdown have been subject to so much projection and politicizing that it is an enormous contribution to see the poet tackle these events in her own words. These letters take the grand archetype of suicidal Plath, the elaborate, brittle mythologies that have sprung up around her, and give them an unforgettable human specificity. What has been missing from the biographical record of the final months is Plath’s own voice.

The saddest thing to watch is how hard she was working to get better. Beuscher advised her not to imagine that she couldn’t exist without Hughes: “First, middle and last, do not give up your personal one-ness.” She warns her not to imagine that her entire life hinges on one particular man. Plath was trying to make her way to the doctor’s words. “The part about keeping my personal one-ness is a real help. I must. But my god I can’t see to thinking straight.”

What comes across so clearly and heartbreakingly in these letters is how hard she is trying. She is actively engaged in the intellectual work of getting better. Beuscher recommends Erich Fromm to her, and she reads and stars a passage: “I have finally read the Fromm & think that I have been guilty of what he calls ‘Idolatrous love,’ that I lost myself in Ted instead of finding myself.”

She wanted so badly to be able to see a life without Hughes, to be able to inhabit it. She could almost see it. She writes to Beuscher, “If I could study, read, enjoy people on my own, Ted’s leaving would be hard, but manageable.” Seven days later, she was dead.

____

*Katie Roiphe is the author of “The Violet Hour: Great Writers at the End,” and the director of the cultural reporting and criticism program at New York University.

*A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 11, 2018, on Page 39 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: Mad Girl’s Love Song.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Courtesy of Bonhams; Everett Collection |

Sylvia Plath’s Darkest Sea:

What an Unveiled Draft Poem Reveals

The drafts for one of Sylvia Plath's last poems will go to auction soon. Olivia Cole uncovers a haunting fragment on the back of a page.

by Olivia Cole

May 3, 2013

Now that her life story is the stuff of myth, it's hard to imagine that when Sylvia Plath killed herself on February 11, 1963, she was the obscure American wife of Ted Hughes, a much more famous British poet. When in June 1960 the couple attended a party at Faber & Faber (Hughes’s publisher), he was photographed, looking shy, standing in the center of the most famous voices of the time. Plath was at the party, but not snapped with the giants. She wrote to her mother Aurelia, “I drank champagne with the appreciation of a housewife on an evening off from the smell of sour milk and diapers. During the course of the party, Charles Monteith, one of the Faber board, beckoned me out into the hall. There Ted stood, flanked by TS Eliot, W H Auden, Louis McNeice [sic] on the one hand and Stephen Spender on the other, having his photograph taken. ‘Three generations of Faber poets there,’ Charles observed. ‘Wonderful!’ Of course, I was tremendously proud. Ted looked very at home among the great.”

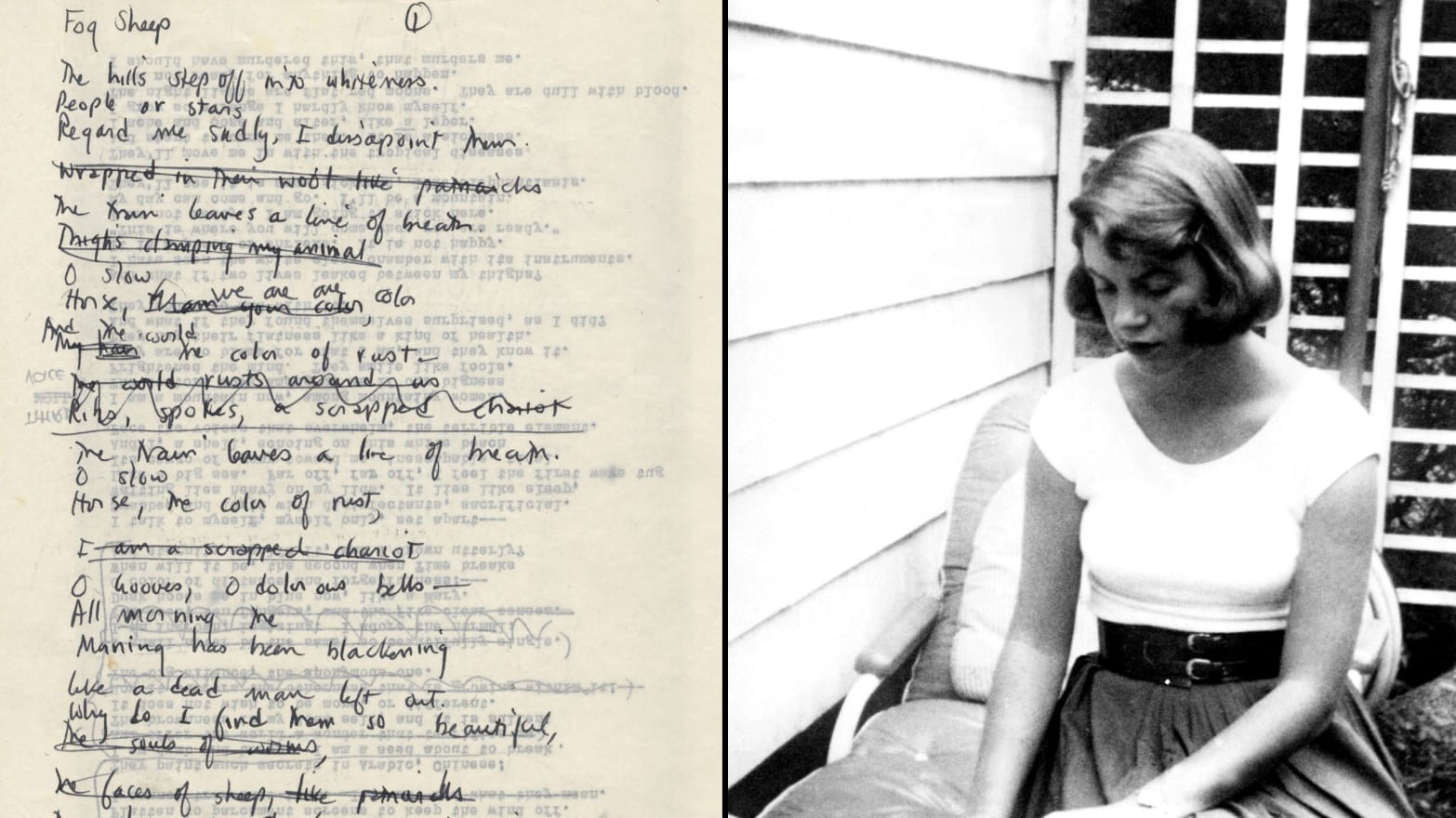

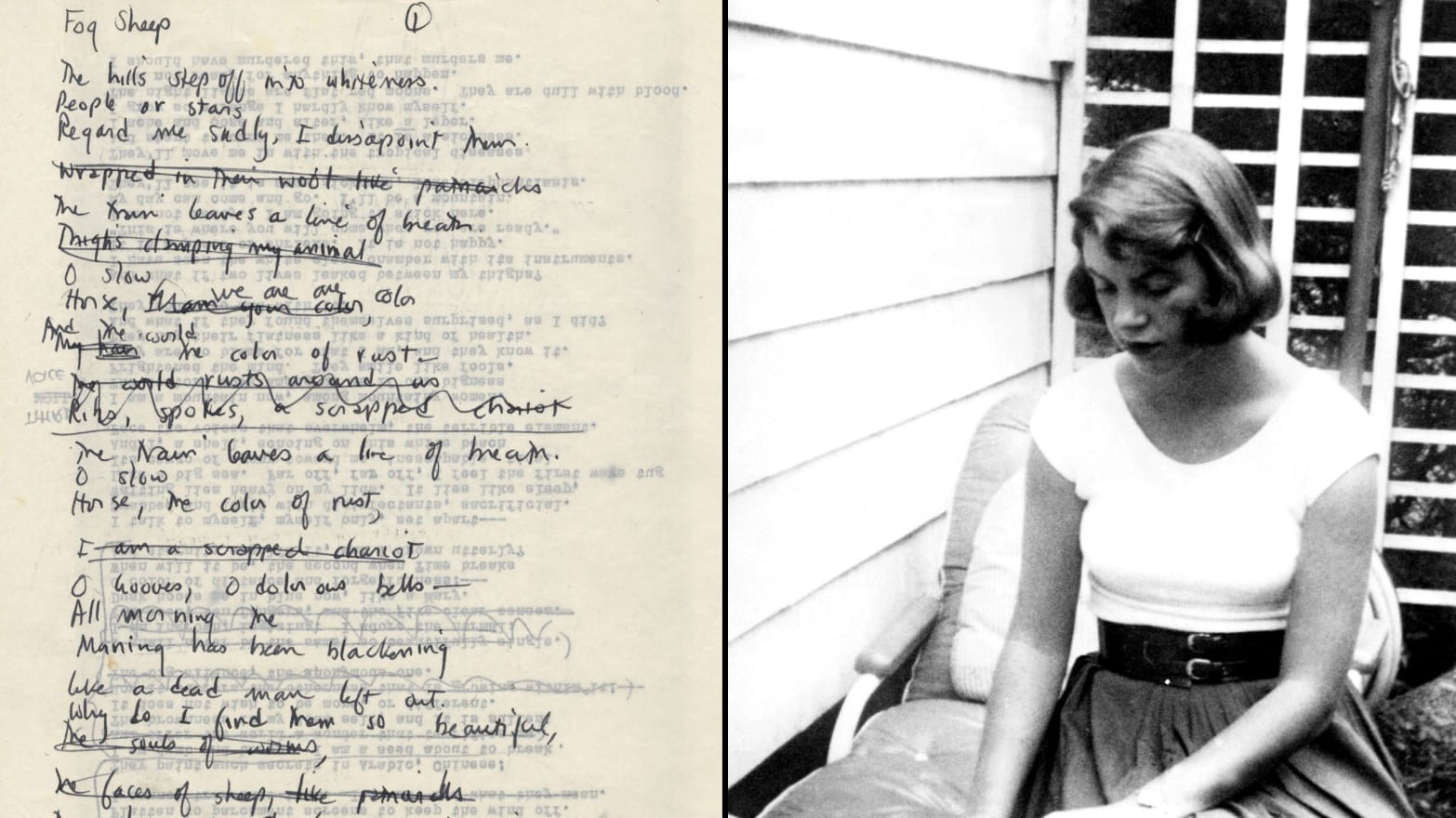

Later, in a scrapbook, Plath wrote underneath her copy of the photograph, “A pride of poets.” Plath’s own first collection, The Colossus, wouldn’t be published until later that year, but today, her own reputation, for the most part resting on the Ariel poems she wrote in the last months of her life, makes her the lioness of that “pride of poets.” Almost all of her drafts and archives are in academic institutions and new material has only rarely been discovered. However, drafts of one of her most famous poems, “Sheep in Fog,” a truly remarkable set of manuscripts written in the last weeks of her life, have recently come onto the market as part of the poetry collection of Roy Davids. A collection put together over 40 years, it is being sold this spring at Bonhams on May 8. The Plath material is estimated to sell for between £30,000 and £35,000 (approximately $45,000 to $53,000) and is likely to break records for the sale of her literary manuscripts.

To anyone who has explored the complex afterlife of Plath and Hughes’s poetry and their tangled archives, Davids is a key figure. A fellow poet, collector, and manuscript dealer, he became a close friend of Hughes’s in the 1970s, when as head of Sotheby’s book department he helped Hughes sell Plath’s own archive to Smith College in Massachusetts and later brokered the controversial and highly lucrative sale of the poet laureate's papers to Emory. When he sold Plath's papers, Hughes kept back a full set of drafts for each of their two children, Nicholas and Frieda, and when later in life Nicholas was short of money, Hughes arranged for Davids to buy them.

To anyone who has explored the complex afterlife of Plath and Hughes’s poetry and their tangled archives, Davids is a key figure. A fellow poet, collector, and manuscript dealer, he became a close friend of Hughes’s in the 1970s, when as head of Sotheby’s book department he helped Hughes sell Plath’s own archive to Smith College in Massachusetts and later brokered the controversial and highly lucrative sale of the poet laureate's papers to Emory. When he sold Plath's papers, Hughes kept back a full set of drafts for each of their two children, Nicholas and Frieda, and when later in life Nicholas was short of money, Hughes arranged for Davids to buy them.

The same poem had also offered the occasion for one of Hughes's, until the publication of Birthday Letters in 1998, very rare meditations on his late wife. In 1987 Davids was giving a lecture on poetic drafts to help Hughes gave him “The Evolution of Sheep in Fog,” later published in Winter Pollen.

“Sheep in Fog” is a beautiful distress signal of a poem. The setting is a dawn ride over Dartmoor, where until the breakdown of their marriage Plath, Hughes and their two small children had been living. Ariel was her horse (named grandly after Shakespeare's flying invisible spirit), and it's from him that she surveys the frozen landscape: "The hills step off into whiteness./People or stars/Regard me sadly, I disappoint them//The train leaves a line of breath. O slow..."

“Sheep in Fog” is a beautiful distress signal of a poem. The setting is a dawn ride over Dartmoor, where until the breakdown of their marriage Plath, Hughes and their two small children had been living. Ariel was her horse (named grandly after Shakespeare's flying invisible spirit), and it's from him that she surveys the frozen landscape: "The hills step off into whiteness./People or stars/Regard me sadly, I disappoint them//The train leaves a line of breath. O slow..."

When I recently went to take a look at these drafts in person, I was astonished to find another footnote to the sad story they contain, one that not even Hughes addressed in his analysis of the poem. (No scholars have yet seen these drafts.) When they lived together Plath and Hughes shared and thriftily recycled paper—a more apt emblem of their creative intimacy would be hard to come by. As Hughes wrote in his poem “Love Song,” the lovers were two brains working out of one head, “in the morning they wore each other's face.” (When in 2000, as a student, I worked at Emory, helping to catalogue the Hughes archive, much of it had to be photocopied and referenced twice because both sides were used by the couple.) By the winter of 1962, living alone, Plath was reusing her own drafts. If she turned over "Fog Sheep" to glance at her own writing on the other side, she would have revisited one of her prose scenes (which seems to be unpublished and unreported until now) in which a girl contemplates a night swim and entertains the possibility of disappearing into the dark water.

"The sea was big, enormous... She thought of all the people in the town asleep in their warm beds, snug, blind against the night, and oh, suddenly she wanted to be a very little girl again. To have somebody tuck her in at night, to cradle her against the colossal dark." Plath writes in the kind of third-person interior monologue she often used for her short stories and early fiction. The sense of "fatherlessness” is here even without thinking of the poem on the other side. The “Colossus,” in fact, was Plath's poetic name for her dead father, whom she reconfigured in her first collection of poems as a watery sea creature to whose deathly embrace she was drawn. Here, "Alison" leaves her raincoat on the beach, keeping a lookout, like the suicidal heroine of The Bell Jar who leaves her heels on the sand when she thinks of swimming out to sea and never coming back.

To her harshest critics Plath, however brilliant, presents a moral problem. She is charged with being the egotistical artist who courted death and her death wish in her writing before going through with it as a final fame grabbing flourish. Hughes knew that was too harsh a view. "The Ariel poems,” he wrote in his essay on “Sheep in Fog,” "document Plath's struggle to deal with a double situation—when her sudden separation from her husband coincided with a crisis in her traumatic feelings about her father's death which had occurred when she was eight-years-old (and which had been complicated by her all but successful attempt to follow him in a suicidal act in 1953). Against these very strong, negative feelings, and others associated with them, her battle to create a new, reborn self, supplies the extraordinary positive resolution of the poems that she wrote up to 2 December 1962."

The "crisis" of course was Hughes's affair with Assia Wevill, but it also precipitated her best work. Like Keats, in a few short months she wrote the poems on which her giant reputation now rests. Heartbreak or no, here you find the "extraordinary" high-wire tricks of reincarnation and regeneration: whatever life throws at her, in the poems at least, Plath is Lady Lazarus, who dies only to be reborn: "Out of the ash/I rise with my red hair/And I eat men like air.” She's a cat with nine lives. It's beautiful myth making—a way of writing but also, you guess, a way of surviving—or trying to survive.

In “Ariel,” a poem from that same streak, the setting again is her dawn ride, but it's totally different from “Sheep in Fog.” As dawn breaks, the rider flies into the eye of the sun, hurtling like Icarus, but also triumphant, a godlike figure, not the sad, grief-stricken woman who two months later sees her horse’s hooves as "dolorous bells." There between the third and fourth version of “Sheep in Fog” is the shift that sets Plath floundering and signals her desperation. The poems that followed are her most desolate: her belief in rebirth no longer works its old magic. In “Totem,” one of her last poems, she wrote of how the “same self unfolds like a suit/Bald and shiny with pockets of wishes//Notions and tickets, short circuits and folding mirrors."

Like so many of Plath's female characters in her prose, Alison is plainly a stand-in for the poet herself. On the beach she casts “herself into the black water," whispering to an unnamed presence that she is coming.

"The night seemed to fall back, withdrawing from her, dark and silent. A star glared at her. The moon sprouted like a puffball in the heavens. If she lay on her back, she could kick the moon. She could split it open with a kick, and the ashes inside would come falling gently down, on her eyes, on her mouth, in a gray coverlet.

At the bottom of the sea a lobster was laughing at her... Foolish Alison, silly girl. She should be in bed where she belonged, asleep her eyes shut tightly, tightly. Let the moon sail by spilling white flour, let the stars fall among the tree leaves. It had nothing to do with her. Nothing at all."

Here is the classic Plath torn between significance and irrelevance—the self that's Lady Lazarus and the one that's a cheap shiny suit. Ted Hughes himself never put much store on Plath's short stories. Most of them were written for the American magazine market, whose needs she had learned to master as a student, but even if produced solely to pay the bills, they rehearse her preoccupations. Did Plath flip the page and cast an eye over Alison in the dark sea as she looked at her floating cloud in the final verse and knew it wouldn't do? It's impossible to tell, but even this prose fragment stages the drama of Plath's extraordinary imagination that still grips us 50 years after her death. In the end, her great power as a poet is in being neither wholly the mythical goddess kicking the moon nor entirely the doubting solitary rider whom even the stars find disappointing, but both: sometimes all on the same piece of paper.

The "crisis" of course was Hughes's affair with Assia Wevill, but it also precipitated her best work. Like Keats, in a few short months she wrote the poems on which her giant reputation now rests. Heartbreak or no, here you find the "extraordinary" high-wire tricks of reincarnation and regeneration: whatever life throws at her, in the poems at least, Plath is Lady Lazarus, who dies only to be reborn: "Out of the ash/I rise with my red hair/And I eat men like air.” She's a cat with nine lives. It's beautiful myth making—a way of writing but also, you guess, a way of surviving—or trying to survive.

In “Ariel,” a poem from that same streak, the setting again is her dawn ride, but it's totally different from “Sheep in Fog.” As dawn breaks, the rider flies into the eye of the sun, hurtling like Icarus, but also triumphant, a godlike figure, not the sad, grief-stricken woman who two months later sees her horse’s hooves as "dolorous bells." There between the third and fourth version of “Sheep in Fog” is the shift that sets Plath floundering and signals her desperation. The poems that followed are her most desolate: her belief in rebirth no longer works its old magic. In “Totem,” one of her last poems, she wrote of how the “same self unfolds like a suit/Bald and shiny with pockets of wishes//Notions and tickets, short circuits and folding mirrors."

Like so many of Plath's female characters in her prose, Alison is plainly a stand-in for the poet herself. On the beach she casts “herself into the black water," whispering to an unnamed presence that she is coming.

"The night seemed to fall back, withdrawing from her, dark and silent. A star glared at her. The moon sprouted like a puffball in the heavens. If she lay on her back, she could kick the moon. She could split it open with a kick, and the ashes inside would come falling gently down, on her eyes, on her mouth, in a gray coverlet.

At the bottom of the sea a lobster was laughing at her... Foolish Alison, silly girl. She should be in bed where she belonged, asleep her eyes shut tightly, tightly. Let the moon sail by spilling white flour, let the stars fall among the tree leaves. It had nothing to do with her. Nothing at all."

Here is the classic Plath torn between significance and irrelevance—the self that's Lady Lazarus and the one that's a cheap shiny suit. Ted Hughes himself never put much store on Plath's short stories. Most of them were written for the American magazine market, whose needs she had learned to master as a student, but even if produced solely to pay the bills, they rehearse her preoccupations. Did Plath flip the page and cast an eye over Alison in the dark sea as she looked at her floating cloud in the final verse and knew it wouldn't do? It's impossible to tell, but even this prose fragment stages the drama of Plath's extraordinary imagination that still grips us 50 years after her death. In the end, her great power as a poet is in being neither wholly the mythical goddess kicking the moon nor entirely the doubting solitary rider whom even the stars find disappointing, but both: sometimes all on the same piece of paper.

____

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that Smith College is in Boston. It’s in Northampton, Massachusetts. We regret the error.