|

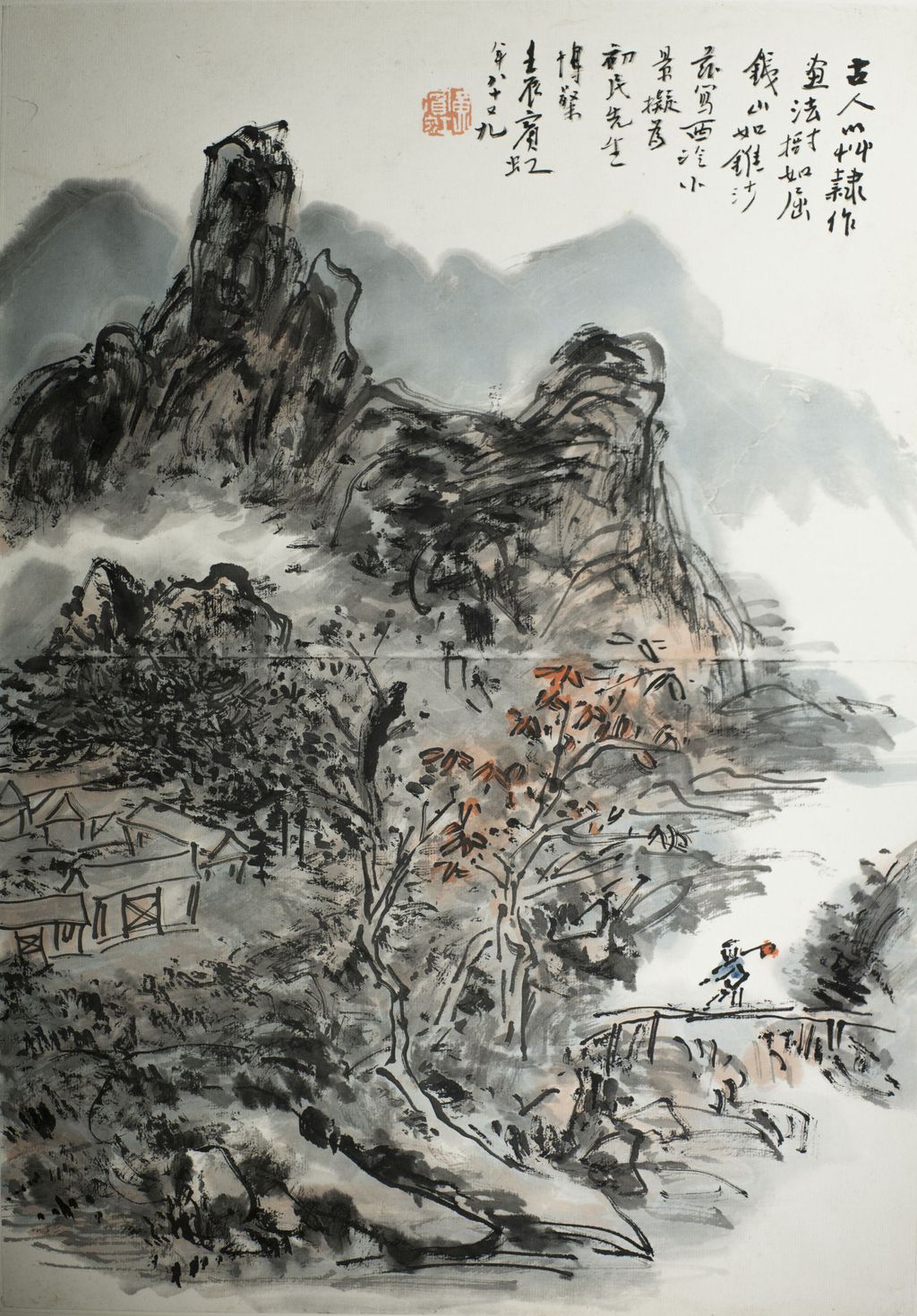

| "Landscapes," album leaf by Huang Binhong. | Image courtesy of Elna Tsao with support from the Mozhai Foundation |

Painting Lost Landscapes,

Spiritual and Physical,

with a Sonic Brush

Lei Liang -

A Thousand Mountains, A Million Streams

Program Note

I always wanted to create music as if painting with a sonic brush. I think in terms of curves and lines, light and shadows, distances, the speed of the brush, textures, gestures, movements and stillness, layering, blurring, coloring, the inter-penetration of ink, brushstrokes, energy, breath, spatial resonance, spiritual vitality, void and emptiness.

A Thousand Mountains, A Million Streams meditates on the loss of landscapes of cultural and spiritual dimensions. The work implies an intention to preserve and resurrect parallel landscapes - both spiritual and physical – and sustain a place where we and our children can belong.

Using a sonic brush, I paint an inner journey: A landscape emerges out of darkness, illuminated by an artist’s inner vision; distant contours, shapes, hints of color, and emptiness. As the viewer draws closer and closer to the landscape, lines and human presence begin to emerge, sounds to resonate, until we become one with each of its brush-strokes and ink splashes, with its every breath. The mountains are breathing, singing and roaring. The landscape vibrates, pulsates and dances; it takes flight; it stirs, swells, rises, grinds, surges, stretches and blooms; trembling, jolting, and collapsing, it breaks into fragments. ... Rain – drops and drops of rain – returns, to heal the landscape in ruin. A prayer, a resurrection, the rain brings life back to the landscapes, and it regains its gentle heartbeat.

--Lei Liang

Lei Liang (b.1972) began his musical studies in China, completing them in the USA. His music aims at a deeper philosophical engagement with musical sound as a tool for reflection and contemplation, while resisting exoticized and formulaic treatment of Asian musical elements. Liang's music is deeply philosophical, yet sensual, evocative, yet abstract, and disciplined, yet spontaneous.

He studied composition with Harrison Birtwistle, Chaya Czernowin, Joshua Fineberg, and Mario Davidovsky, and received degrees from the New England Conservatory of Music and Harvard University. He now teaches at UCSD (San Diego).

• Written for the Arditti String Quartet, Serashi Fragments is a tribute to the Mongolian chaoer (fiddler) Serashi (1887-1968). In this highly virtuosic piece, Liang deploys a wide range of articulation for strings: pizzicato sul pont, stacatissimo, Bartók pizzicato, glissando, harmonics, and glissando harmonics.

• In Some Empty Thoughts of a Person from Edo, Liang expands the timbral possibilities of the harpsichord through introducing "lute stops," clusters formed by the palm and fingers of each hand, along with other extended devices. A plucked passage with arpeggiated chords is reminiscent of the Japanese koto.

• Memories of Xiaoxiang for saxophone and tape presents a personal commentary on Liang's cultural past, including field recordings in the tape part.

• In Praise of Shadows for solo flute is a piece that invites philosophical contemplation on the duality of light and shadow, embodied by the barely audible partials in the multiphonics, whistling tones, or the downward portamento Liang often uses to end a phrase.

• Brush-Stroke allows the listener to be immersed in the transience of each sound as it comes into being and passes away. It is reminiscent of Japanese gagaku and Korean Aak court music.

• Liner notes by Yayoi Uno Everett.

Lei Liang - Brush Stroke

|

| Additional Recordings w/Analysis - click here |

Review in NY Times

"Over 30 minutes, the work unfurls a fluid stream of instrumental colors, from shimmering filaments of sound to broad sighing gestures that build with unrelenting momentum into muscular blocks of dark matter. A series of brutal percussive slashes leads to scorched silence. In the end, droplets of sound evoke a fragile rebirth.

The work is intended as a reflection on the man-made destruction of both natural landscapes and cultural ecosystems, and highlights the power of art to preserve them — at least in memory. Mr. Liang teaches at the University of California at San Diego and has collaborated with scientists on innovative ways to record the sounds of Pacific Ocean coral reefs and Arctic fauna.

“We have the external world that we need to protect,” he said in the interview. At the same time, he warns against the kind of self-inflicted damage to a culture’s spiritual heritage that he feels left lasting wounds in his native China: “There is also an internal world that we need to nurture, because it can vanish very rapidly.”

-- Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim, NY Times

|

| Sonic Artist Lei Liang |

SCORCHED SILENCE, FRAGILE REBIRTH, AWARD-WINNING MUSIC

The New York Times

by Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim

December 13, 2019

The apartment building in which the composer Lei Liang grew up, in Beijing in the 1970s, was a musicological beehive. Its residents worked at the Music Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Arts, which had an archive of rare historical recordings that had been saved, often at great personal cost, from destruction in the Cultural Revolution.

Mr. Liang’s father was an authority on Chinese opera; his mother, an expert on American music. Many evenings, a Mongolian friend of the family would drop by for drinks and impromptu performances of war songs, dances and epic poems.

On one wall of the apartment hung a photograph of Mr. Liang’s mother interviewing Aaron Copland in his Westchester, N.Y., home. Years later, as a young composer, Mr. Liang came to live and work there when he won a residency at Copland House, now a foundation.

“Because of that photo,” he said in a recent phone interview, “I found that environment strangely familiar.”

The emotional resonance of fragile environments, both natural and cultural, is captured in haunting ways in the music of Mr. Liang, 47, who this month was honored with the Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition, one of the most prestigious prizes in contemporary music. He won for an orchestral work, “A Thousand Mountains, a Million Streams,” inspired by a landscape painting by the Chinese ink-brush master Huang Binhong (1865-1955).

Over 30 minutes, the work unfurls a fluid stream of instrumental colors, from shimmering filaments of sound to broad sighing gestures that build with unrelenting momentum into muscular blocks of dark matter. A series of brutal percussive slashes leads to scorched silence. In the end, droplets of sound evoke a fragile rebirth.

The work is intended as a reflection on the man-made destruction of both natural landscapes and cultural ecosystems, and highlights the power of art to preserve them — at least in memory. Mr. Liang teaches at the University of California at San Diego and has collaborated with scientists on innovative ways to record the sounds of Pacific Ocean coral reefs and Arctic fauna.

“We have the external world that we need to protect,” he said in the interview. At the same time, he warns against the kind of self-inflicted damage to a culture’s spiritual heritage that he feels left lasting wounds in his native China: “There is also an internal world that we need to nurture, because it can vanish very rapidly.”

Here are edited excerpts from the conversation:

What drew you to the painting that inspired “A Thousand Mountains”?

Huang Binhong painted this particular set of magnificent landscapes late in life, when he was almost blind. I was fascinated by how a person could use his inner vision to create something even more beautiful than reality, with the environment collapsing.

What are some aspects of the painting that made it into the music?

Huang Binhong made this remark that you have to use white as black. He was referring to void and emptiness that are as substantial as that which is painted with ink. I apply that to my music in a very concrete way. I have a lot of emptiness and silence in the music. I think of those moments as containers of memory and historical resonance.

The end of “A Thousand Mountains” recalls water, with plucked strings and subtle percussion effects, but without using the amplified sounds of actual water, as some of your colleagues might do. Why?

That’s a lesson I learned from traditional Peking Opera: You do not portray anything realistically. In Peking opera alone there were more than a hundred kinds of coughing sounds. Depending on the role types and what the cough symbolizes — whether you’re entering or interrupting a conversation — it was expressed in a particular vocal way. I was very inspired by this idea to not portray things realistically, but to find an imaginative way to filter an idea and distill it using purely instrumental means.

“A Thousand Mountains” is itself the result of a process of distillation, isn’t it?

Yes, and it’s very much about recovering and reimagining my own history. I was acutely aware of how fragile my own cultural and spiritual landscapes are. After I started working on this project, which started with the analysis of the landscape painting and going through electronic music experimentation and transforming that into an experience using purely acoustic instruments, I discovered the connection of the inner landscape that was disappearing before our eyes and how that parallels the environmental landscape that is collapsing around us.

Were there specific examples of environmental depredation that came to mind?

The first time I went back to China, six years after moving to America, I lost my voice because of the pollution. I didn’t recognize my own city. I also think of Mongolia, whose music was one of my earliest loves, and of the sand storms that now come in from the desert there, which some researchers have attributed to the overconsumption of beef in China. And, of course, now in California there are the fires that affect us and personal friends.

You have spoken of the cultural epiphany you experienced when you arrived in the United States at 17. How did the move change you?

I discovered China in America. It was only in Austin, Tex., and then during my 14 years in Boston studying at the New England Conservatory and Harvard, that I really reconstructed my family’s past, my culture’s past. These were things that we hadn’t been taught — in fact things that were denied. I hand-copied Buddhist and Taoist classics and treatises on paintings. I learned the traditional Chinese characters on my own because I had not been taught them in mainland China.

It takes some effort and even struggle to earn a membership in a cultural community. I mean, I was born a Chinese citizen. But to be Chinese culturally and spiritually? That is a process, a cultivation and, in the end, a path of self-discovery. It’s about what we choose to inherit.

The study of calligraphy, poetry and traditional painting were central to the Chinese concept of the wenren, or Renaissance man. How do you identify with that term?

It’s a challenge to see myself as a vessel, as an imaginative and creative force that has a place in history — so that you create while you preserve at the same time. Today, in a different world, that encompasses the environmental, cultural and spiritual responsibilities an artist has.

*wenren - The Qing literati (wenren Chinese:文人) were officially designated as literate or cultivated persons. Parallel to wenren are two terms, "shi"(Chinese:士), scholar, and "shen"(Chinese:绅), often defined as gentry or official. - Wikipedia