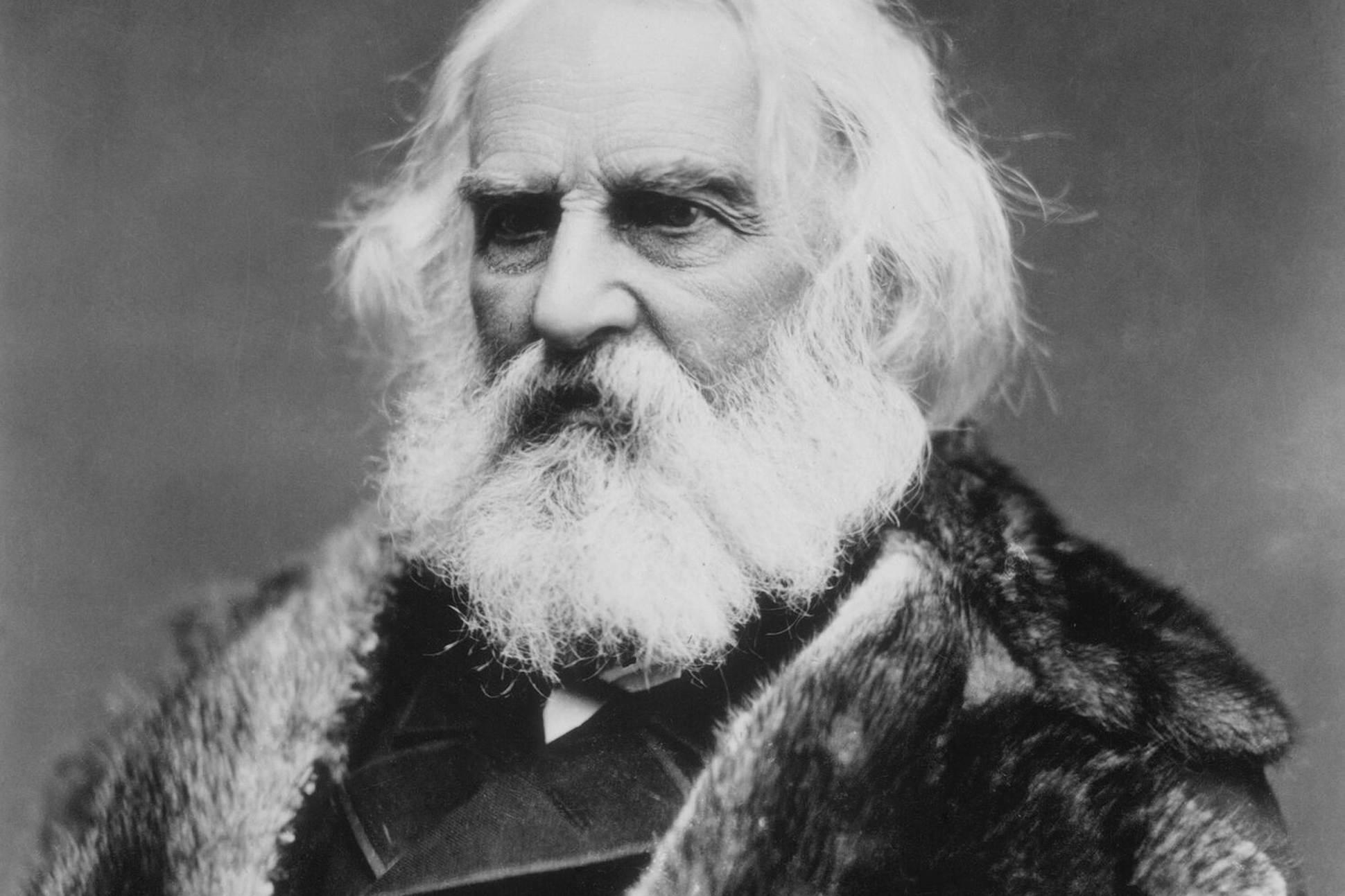

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, one of the "Fireside Poets," wrote lyrical poems about history, mythology, and legend that were popular and widely translated, making him the most famous American of his day.

|

Eastman Johnson, Christmas Time |

|

| Print of Thomas Buchanan Read's portrait of Longfellow's three daughters, Alice, Edith and Anne Allegra |

* * * * * * *

Wikipedia - The poem describes the poet's idyllic family life with his own three daughters, Alice, Edith, and Anne Allegra:[1] "grave Alice, and laughing Allegra, and Edith with golden hair." As the darkness begins to fall, the narrator of the poem (Longfellow himself) is sitting in his study and hears his daughters in the room above. He describes them as an approaching army about to enter through a "sudden rush" and a "sudden raid" via unguarded doors. Climbing into his arms, the girls "devour" their father with kisses, who in turn promises to keep them forever in his heart.

THE CHILDREN'S HOUR

by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882)

Between the dark and the daylight,

When the night is beginning to lower

Comes a pause in the day's occupations,

That is known as the Children's Hour.

I hear in the chamber above me

The patter of little feet,

The sound of a door that is opened,

And voices soft and sweet.

From my study I see in the lamplight,

Descending the broad hall stair,

Grave Alice, and laughing Allegra,

And Edith with golden hair.

A whisper, and then a silence:

Yet I know by their merry eyes

They are plotting and planning together

To take me by surprise.

A sudden rush from the stairway,

A sudden raid from the hall!

By three doors left unguarded

They enter my castle wall!

They climb up into my turret

O'er the arms and back of my chair;

If I try to escape, they surround me;

They seem to be everywhere.

They almost devour me with kisses,

Their arms about me entwine,

Till I think of the Bishop of Bingen

In his Mouse-Tower on the Rhine!

Do you think, o blue-eyed banditti,

Because you have scaled the wall,

Such an old mustache as I am

Is not a match for you all!

I have you fast in my fortress,

And will not let you depart,

But put you down into the dungeon

In the round-tower of my heart.

And there will I keep you forever,

Yes, forever and a day,

Till the walls shall crumble to ruin,

And moulder in dust away!

When the night is beginning to lower

Comes a pause in the day's occupations,

That is known as the Children's Hour.

I hear in the chamber above me

The patter of little feet,

The sound of a door that is opened,

And voices soft and sweet.

From my study I see in the lamplight,

Descending the broad hall stair,

Grave Alice, and laughing Allegra,

And Edith with golden hair.

A whisper, and then a silence:

Yet I know by their merry eyes

They are plotting and planning together

To take me by surprise.

A sudden rush from the stairway,

A sudden raid from the hall!

By three doors left unguarded

They enter my castle wall!

They climb up into my turret

O'er the arms and back of my chair;

If I try to escape, they surround me;

They seem to be everywhere.

They almost devour me with kisses,

Their arms about me entwine,

Till I think of the Bishop of Bingen

In his Mouse-Tower on the Rhine!

Do you think, o blue-eyed banditti,

Because you have scaled the wall,

Such an old mustache as I am

Is not a match for you all!

I have you fast in my fortress,

And will not let you depart,

But put you down into the dungeon

In the round-tower of my heart.

And there will I keep you forever,

Yes, forever and a day,

Till the walls shall crumble to ruin,

And moulder in dust away!

* * * * * * *

The Children’s Hour by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

by Andrew Walker, Andrew

If you’ve ever tried to convey a sarcastic remark through a written medium, you probably already know how difficult it can be to convey tone through text. For poets, this can be a very difficult mechanic to employ, but a very powerful one at the same time — not because poets are sarcastic people, but because of how useful it can be to play with connotations and denotations and take advantage of a reader’s predispositions. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow proves himself, again and again, to be very adept at using tone to enhance the messages within his poem, and The Children’s Hour is an excellent example of his use of the tool to convey the idea of his titular phenomenon.

The Children’s Hour Analysis

Between the dark and the daylight,

When the night is beginning to lower,

Comes a pause in the day’s occupations,

That is known as the Children’s Hour.

–

I hear in the chamber above me

The patter of little feet,

The sound of a door that is opened,

And voices soft and sweet.

The Children’s Hour is written very lyrically, using the same rhythm and rhyming structure from beginning to end, without any kind of emphatic break or pause. The rhyme and flow helps the poem to pick up an easygoing kind of atmosphere — poems just sound nicer when they can essentially be sung. The first verse is also crucial in establishing atmosphere, and this seems to be its only read purpose. The grammatical structure of the verse is what is most interesting, specifically that there is no subject, and the entire verse is written in passive voice. It talks about a time and talks about a name, but gives no story or purpose to either; whose occupations are paused? Who calls this the Children’s Hour? Whose children are they? None of this is established, which makes the information presented sound just a little cryptic, and a lot like fact. It’s meant to be intriguing and disarming, and largely succeeds.

The second verse, on the other hand, has a narrator, who describes the early events of the Children’s Hour for the reader. The meaning of the verse is straightforward enough — the speaker can hear light footsteps and voices from people leaving the room above. Longfellow’s word choice is interesting though — he describes the “patter” and the “soft and sweet” voices, words typical of describing children, and he also describes their room as a “chamber,” which is more typical of a castle hall or dungeon than a nursery. The word is completely unneeded from a structural standpoint — “room” would have fit just as easily, if not more, since it would have made the line the same number of syllables as the first line of the previous verse. “Chamber” holds conflicting connotation with the rest of the verse, and this makes it what is likely a very intentional choice by the author.

From my study I see in the lamplight,

Descending the broad hall stair,

Grave Alice, and laughing Allegra,

And Edith with golden hair.

–

A whisper, and then a silence:

Yet I know by their merry eyes

They are plotting and planning together

To take me by surprise.

The second and third verses describe the children arriving to the speaker’s study, and they follow a similar structure in tone to the verses before them. Allegra is laughing, Edith is golden, and Alice is grave, and that last adjective is a truly odd one to find in the bunch. The children’s eyes are merry, yet they are plotting. What is interesting here is that these changes in description, these words that don’t belong, do not detract from the cheerful atmosphere; rather, the reader tries to imagine the words has having other meanings. It makes more sense to think that Alice is simply taking the plan very seriously than it does to imagine one of these children as being cold and serious. This is a triumph of The Children’s Hour’s tonal developments so early in the work.*

A sudden rush from the stairway,

A sudden raid from the hall!

By three doors left unguarded

They enter my castle wall!

–

They climb up into my turret

O’er the arms and back of my chair;

If I try to escape, they surround me;

They seem to be everywhere.

At this point in the poem, it’s fairly clear that the speaker’s children are the subjects of the work, so when Longfellow continues to describe their embrace as a fortress raid, the idea becomes endearing, rather than threatening. The tone of the work is influencing the reader’s perceived meaning of each word — so here, he uses many more words that might otherwise be considered dark additions to a story, such as “rush,” “raid,” “unguarded,” “wall,” “turret,” “escape,” and “surround.” There are a lot of them! But in this context, it’s more cute than threatening, and it seems that he may be describing events as they take place in the children’s minds, rather than the speaker’s own. It makes sense to think of young kids as imagining that they are invading a castle, and that the study chair is an outpost, with their parent as the object of a daring raid. In this context, the poem feels even more fun than previously.

They almost devour me with kisses,

Their arms about me entwine,

Till I think of the Bishop of Bingen

In his Mouse-Tower on the Rhine!

–

Do you think, o blue-eyed banditti,

Because you have scaled the wall,

Such an old moustache as I am

Is not a match for you all!

After the children reach the study chair, the speaker begins to imagine themselves as a part of the children’s story. The reference to the Bishop of Bingen is somewhat obscure — in popular medieval legend, he was a cruel and unfair leader who’s tower was invaded by rats as punishment for a famine he did little to avoid or help his subjects through. The speaker, however, feels more confident than the Bishop, and warns his children that reaching the tower was the easy part and that there is one guard they cannot get past, namely their own father (judging from the self-described “old moustache”). He places himself within the story and calls them “banditti,” a group of outlaws befitting of their narrative.

I have you fast in my fortress,

And will not let you depart,

But put you down into the dungeon

In the round-tower of my heart.

–

And there will I keep you forever,

Yes, forever and a day,

Till the walls shall crumble to ruin,

And moulder in dust away!

Tonally, The Children’s Hour is much benefitted when the father of the children embraces their narrative, and the story in the final four verses becomes about embracing that story and making it a part of the poem itself. Of course, because this is the Children’s Hour, the father will not allow his children to leave the “fortress,” returning their affection and promising to love them forever, still using their own story as his means of doing so — the “round-tower of my heart” is a somewhat literal metaphor, but it works here. The image of the tower crumbling to dust is a sad image to end off the poem, because it more than likely symbolizes the death of the father, who is saying that not a day will go by in his life that he will not love his children. It is a very sweet adaptation of the love a father has for his children, which is almost certainly the inspiration of the poem. Alice, Edith, and Anne Allegra Longfellow are the name of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s first three children, a fact which makes the playful and childish narrative of The Children’s Hour much, much sweeter to contemplate.

* * * * * * *

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

1807–1882

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine—then still part of Massachusetts—on February 27, 1807, the second son in a family of eight children. His mother, Zilpah Wadsworth, was the daughter of a Revolutionary War hero. His father, Stephen Longfellow, was a prominent Portland lawyer and later a member of Congress.

After graduating from Bowdoin College, Longfellow studied modern languages in Europe for three years, then returned to Bowdoin to teach them. In 1831 he married Mary Storer Potter of Portland, a former classmate, and soon published his first book, a description of his travels called Outre Mer ("Overseas"). But in November 1835, during a second trip to Europe, Longfellow's life was shaken when his wife died during a miscarriage. The young teacher spent a grief-stricken year in Germany and Switzerland.

Longfellow took a position at Harvard in 1836. Three years later, at the age of thirty-two, he published his first collection of poems, Voices of the Night, followed in 1841 by Ballads and Other Poems. Many of these poems ("A Psalm of Life," for example) showed people triumphing over adversity, and in a struggling young nation that theme was inspiring. Both books were very popular, but Longfellow's growing duties as a professor left him little time to write more. In addition, Frances Appleton, a young woman from Boston, had refused his proposal of marriage.

Frances finally accepted his proposal the following spring, ushering in the happiest eighteen years of Longfellow's life. The couple had six children, five of whom lived to adulthood, and the marriage gave him new confidence. In 1847, he published Evangeline, a book-length poem about what would now be called "ethnic cleansing." The poem takes place as the British drive the French from Nova Scotia, and two lovers are parted, only to find each other years later when the man is about to die.

In 1854, Longfellow decided to quit teaching to devote all his time to poetry. He published Hiawatha, a long poem about Native American life, and The Courtship of Miles Standish and Other Poems. Both books were immensely successful, but Longfellow was now preoccupied with national events. With the country moving toward civil war, he wrote "Paul Revere's Ride," a call for courage in the coming conflict.

A few months after the war began in 1861, Frances Longfellow was sealing an envelope with wax when her dress caught fire. Despite her husband's desperate attempts to save her, she died the next day. Profoundly saddened, Longfellow published nothing for the next two years. He found comfort in his family and in reading Dante’s Divine Comedy. (Later, he produced its first American translation.) Tales of a Wayside Inn, largely written before his wife's death, was published in 1863.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the poet was fifty-eight. His most important work was finished, but his fame kept growing. In London alone, twenty-four different companies were publishing his work. His poems were popular throughout the English-speaking world, and they were widely translated, making him the most famous American of his day. His admirers included Abraham Lincoln, Charles Dickens, and Charles Baudelaire.

From 1866 to 1880, Longfellow published seven more books of poetry, and his seventy-fifth birthday in 1882 was celebrated across the country. But his health was failing, and he died the following month, on March 24. When Walt Whitman heard of the poet's death, he wrote that, while Longfellow's work "brings nothing offensive or new, does not deal hard blows," he was the sort of bard most needed in a materialistic age: "He comes as the poet of melancholy, courtesy, deference—poet of all sympathetic gentleness—and universal poet of women and young people. I should have to think long if I were ask'd to name the man who has done more and in more valuable directions, for America."

* * * * * * *

More References

No comments:

Post a Comment