The Taking of Teach the Pirate

by Benjamin Franklin - 1719

The poem recounts the last hours of Blackbeard's life as he fought against Lieutenant Robert Maynard and his sailors. Sent out to capture the loathed pirate by Alexander Spotswood, Royal Governor of Virginia, Lieutenant Maynard cornered Blackbeard at Ocracoke Island off the coast of North Carolina. After a short battle on the morning of November 22, 1718, Blackbeard was dead, his severed head proudly displayed from the HMS Jane, as Lieutenant Maynard sailed home to claim the prize for killing such a despised soul.

Seaward they scudded and skipped on the breeze,

Searching for treasure to plunder and seize.

Riches, regrettably, couldn’t be found.

Ships bearing booty were nowhere around.

Therefor the buccaneers wandered afloat

thinking of things they could do with their boat.

Bluebeard said, “Aargh, since we’ve nothing to do,

Why don’t we paint our new pirate ship blue?”

Redbeard spoke up, saying, “Aye, but instead,

wouldn’t ye rather we painted her red?”

Blackbeard said, “Blimey, you’re both off the track.

No other color’s as handsome as black.”

“Blue!” shouted Bluebeard, and Redbeard yelled “Red!”

Blackbeard said, “Black! You’re both cracked in the head!”

Redbeard grabbed brushes and buckets and paints

Over his shipmates insistent complaints.

Rather than letting him paint the ship red,

They got some blue paint and black paint instead.

Swiftly the three of them painted their boat,

Each a completely dissimilar coat,

Making a color not red, black or blue;

Mixing, instead, an entirely new hue.

That was the last that was seen of the three

Simply because they refused to agree.

They weren’t torpedoed or shelled or harpooned.

They disappeared, for their ship was marooned.

Kenn Nesbitt

|

| This most famous fictional pirate was real |

Pirate music about a pirate ship that goes on many dangerous expeditions and adventures in search of gold and treasures. This music is called The Jolly Roger. We hope you enjoy it!

Avast ye, hearties: Tuesday, September 19 is National Talk Like a Pirate Day and you don’t want to look like a scallywag. Captain Syntax shares a few useful phrases in this video so your pirate lingo will sound like that of an old salt, matey. And don’t forget the rum… er, grog.

William Henry Davies (1871 - September 26, 1940), was a Welsh poet and writer. He spent most of his life as a tramp in the United States and United Kingdom, but became known as one of the most popular poets of his time.

He was born in Newport, Monmouthshire, where his father died when he was two years old. His mother then abandoned him and his siblings when she remarried, leaving them to be brought up by their grandparents.

He was a difficult and somewhat delinquent young man, and after failing to settle as an apprentice, took casual work and travelled. The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp (1908) is an account of his times in the USA 1893 - '99, during which he lived as a vagrant. He lost a leg while jumping a train in Canada, and wore a wooden leg.

He returned to England, living a rough life in London in particular. His first book of poetry, in 1905, was the beginning of success and a growing reputation; he drew extensively on his experiences with the seamier side for material. By the time of his prominent place in the Edward Marsh Georgian poetry series, he was an established figure. He is generally best known for two lines from his poem, Leisure:

- What is this life if, full of care,

- We have no time to stand and stare.

He married in 1923 Helen Payne, an ex-prostitute and his junior by three decades; his frank account of how this came about was only published in 1980. They lived quietly in Sussex and Gloucestershire.

A dear old couple my grandparents were,

And kind to all dumb things; they saw in Heaven

The lamb that Jesus petted when a child;

Their faith was never draped by Doubt: to them

Death was a rainbow in Eternity,

That promised everlasting brightness soon.

An old seafaring man was he; a rough

Old man, but kind; and hairy, like the nut

Full of sweet milk.

All day on shore he watched

The winds for sailors' wives, and told what ships

Enjoyed fair weather, and what ships had storms;

He watched the sky, and he could tell for sure

What afternoons would follow stormy morns,

If quiet nights would end wild afternoons.

He leapt away from scandal with a roar,

And if a whisper still possessed his mind,

He walked about and cursed it for a plague.

He took offence at Heaven when beggars passed,

And sternly called them back to give them help.

In this old captain's house I lived, and things

That house contained were in ships' cabins once:

Sea-shells and charts and pebbles, model ships;

Green weeds, dried fishes stuffed, and coral stalks;

Old wooden trunks with handles of spliced rope,

With copper saucers full of monies strange,

That seemed the savings of dead men, not touched

To keep them warm since their real owners died;

Strings of red beads, methought were dipped in blood,

And swinging lamps, as though the house might move;

An ivory lighthouse built on ivory rocks,

The bones of fishes and three bottled ships.

And many a thing was there which sailors make

In idle hours, when on long voyages,

Of marvellous patience, to no lovely end.

And on those charts I saw the small black dots

That were called islands, and I knew they had

Turtles and palms, and pirates' buried gold.

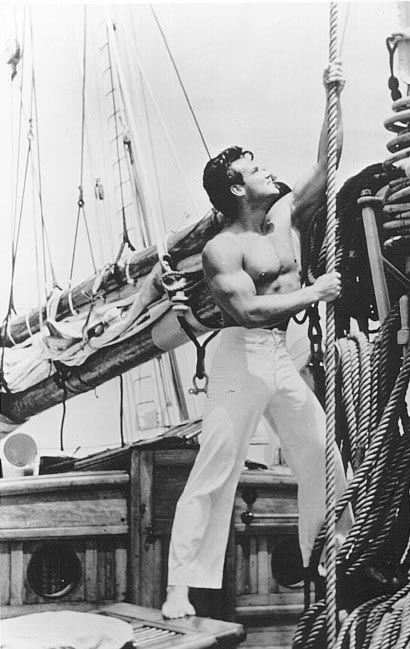

There came a stranger to my granddad's house,

The old man's nephew, a seafarer too;

A big, strong able man who could have walked

Twm Barlum's hill all clad in iron mail

So strong he could have made one man his club

To knock down others -- Henry was his name,

No other name was uttered by his kin.

And here he was, sooth illclad, but oh,

Thought I, what secrets of the sea are his!

This man knows coral islands in the sea,

And dusky girls heartbroken for white men;

More rich than Spain, when the Phoenicians shipped

Silver for common ballast, and they saw

Horses at silver mangers eating grain;

This man has seen the wind blow up a mermaid's hair

Which, like a golden serpent, reared and stretched

To feel the air away beyond her head.

He begged my pennies, which I gave with joy --

He will most certainly return some time

A self-made king of some new land, and rich.

Alas that he, the hero of my dreams,

Should be his people's scorn; for they had rose

To proud command of ships, whilst he had toiled

Before the mast for years, and well content;

Him they despised, and only Death could bring

A likeness in his face to show like them.

For he drank all his pay, nor went to sea

As long as ale was easy got on shore.

Now, in his last long voyage he had sailed

From Plymouth Sound to where sweet odours fan

The Cingalese at work, and then back home --

But came not near my kin till pay was spent.

He was not old, yet seemed so; for his face

Looked like the drowned man's in the morgue, when it

Has struck the wooden wharves and keels of ships.

And all his flesh was pricked with Indian ink,

His body marked as rare and delicate

As dead men struck by lightning under trees

And pictured with fine twigs and curlèd ferns;

Chains on his neck and anchors on his arms;

Rings on his fingers, bracelets on his wrist;

And on his breast the Jane of Appledore

Was schooner rigged, and in full sail at sea.

He could not whisper with his strong hoarse voice,

No more than could a horse creep quietly;

He laughed to scorn the men that muffled close

For fear of wind, till all their neck was hid,

Like Indian corn wrapped up in long green leaves;

He knew no flowers but seaweeds brown and green,

He knew no birds but those that followed ships.

Full well he knew the water-world; he heard

A grander music there than we on land,

When organ shakes a church; swore he would make

The sea his home, though it was always roused

By such wild storms as never leave Cape Horn;

Happy to hear the tempest grunt and squeal

Like pigs heard dying in a slaughterhouse.

A true-born mariner, and this his hope --

His coffin would be what his cradle was,

A boat to drown in and be sunk at sea;

Salted and iced in Neptune's larder deep.

This man despised small coasters, fishing-smacks;

He scorned those sailors who at night and morn

Can see the coast, when in their little boats

They go a six days' voyage and are back

Home with their wives for every Sabbath day.

Much did he talk of tankards of old beer,

And bottled stuff he drank in other lands,

Which was a liquid fire like Hell to gulp,

But Paradise to sip.

And so he talked;

Nor did those people listen with more awe

To Lazurus -- whom they had seen stone dead --

Than did we urchins to that seaman's voice.

He many a tale of wonder told: of where,

At Argostoli, Cephalonia's sea

Ran over the earth's lip in heavy floods;

And then again of how the strange Chinese

Conversed much as our homely Blackbirds sing.

He told us how he sailed in one old ship

Near that volcano Martinique, whose power

Shook like dry leaves the whole Caribbean seas;

And made the sun set in a sea of fire

Which only half was his; and dust was thick

On deck, and stones were pelted at the mast.

Into my greedy ears such words that sleep

Stood at my pillow half the night perplexed.

He told how isles sprang up and sank again,

Between short voyages, to his amaze;

How they did come and go, and cheated charts;

Told how a crew was cursed when one man killed

A bird that perched upon a moving barque;

And how the sea's sharp needles, firm and strong,

Ripped open the bellies of big, iron ships;

Of mighty icebergs in the Northern seas,

That haunt the far hirizon like white ghosts.

He told of waves that lift a ship so high

That birds could pass from starboard unto port

Under her dripping keel.

Oh, it was sweet

To hear that seaman tell such wondrous tales:

How deep the sea in parts, that drownèd men

Must go a long way to their graves and sink

Day after day, and wander with the tides.

He spake of his own deeds; of how he sailed

One summer's night along the Bosphorus,

And he -- who knew no music like the wash

Of waves against a ship, or wind in shrouds --

Heard then the music on that woody shore

Of nightingales,and feared to leave the deck,

He thought 'twas sailing into Paradise.

To hear these stories all we urchins placed

Our pennies in that seaman's ready hand;

Until one morn he signed on for a long cruise,

And sailed away -- we never saw him more.

Could such a man sink in the sea unknown?

Nay, he had found a land with something rich,

That kept his eyes turned inland for his life.

'A damn bad sailor and a landshark too,

No good in port or out' -- my granddad said.

Here's a virtual movie of a reading of an old English seafaring Poem that is often sung as a sort of sea shanty "The Salcombe Seaman's Flaunt to the proud Pirate" There isn't a known author or date of origin for this memorable piece of sea poetry. I have employed the visual services of an old Sea Dog to be our reader me hearties.

|

| An ink drawing of A Broadside |

A LOFTY ship from Salcombe came,

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

She had golden trucks that shone like flame,

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

"Look out and round; d' ye see a sail?"

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

"Her banner aloft it blows out red,"

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

"Are you man-of-war, or privateer?"

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

"I will rummage through your after hold,"

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

Till the pirate's mast went overboard,

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

Was blood and spars and broken wreck,

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

"O keep all fast until we drown,"

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

They sang their songs until she sank,

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

And drink a bowl to the Salcombe ship,

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

Blow high, blow low, and so sailed we;

Who put the pirate ship to shame,

On the bonny coasts of Barbary.

I soon got used to this singing, for the sailors never touched a rope without it . . . Some sea captains, before shipping a man, always ask him whether he can sing out at a rope.

–Herman Melville, Redburn

It’s the 19th century. You’re a young man seeking adventure and a test of your manhood. You decide to sign up on a ship to see exotic foreign lands. You take the trip to the coast. You find a big coastal town and you walk through the docks admiring the ships. Finally, you spot one that you like. You walk on deck and a tall man dressed in black coat confronts you. It’s the captain.

“What do you want lad?”

“I want to sign on board sir,” you say.

He looks you up and down, and says “Aye. But first I need to give you a test.”

You’re not worried. You were expecting this and, in fact, hoping for it. You want to show the captain what you can do. After all, you were always the strongest out of all your friends. You could climb up any rock or tree since you learned how to walk. And you also knew a bit about navigation from your grandfather. You were eager to show what a great addition to the crew you’d make.

“How well can you sing?” the captain asks.

Sea Shanties were work songs sung on ships during the age of sail. They were used to keep rhythm during work and make it more pleasant. Because these songs were used to accomplish a goal, rather then for pure entertainment, the lyrics and melody were not very sophisticated. Still, the songs were usually meaningful and told of a sailor’s life, which included backbreaking labor, abuse from captain and crew, alcohol, and longing for girls and dry land.

Shantyman: Our boots and clothes are all in pawn

Sailors: Go(pull) down ye blood red roses, go(pull) down.

A very popular halyard shanty among modern shantymen. The Spongebob Squarepants theme is a variation of this tune. The version sung on ships usually told about a policeman accusing a sailor of being a black baller and the insulted sailor knocking the policeman down and ending up in jail. The modern version usually tells a story about a sailor meeting a pretty young damsel. The title and chorus refer to the abuse sailors endured on the ships of the Black Ball line.

A capstan shanty of African-American origin. The song told about the indulgences sailors dreamed of partaking once they came on shore. It was very easy to add lyrics to it, and so individual sailors would list things they loved most that “wouldn’t do them any harm.”The line, “A drop of Nelson’s blood wouldn’t do us any harm,” refers to Horatio Nelson whose body was put in a casket of brandy following his death at the battle of Trafalgar.

This one was a forecastle song. Originally an English song, it was later rewritten by American sailors to tell about a victorious battle with pirates disguised as another ship. The pirates pleaded for mercy but the sailors gave them no quarter.

This is the song that you can hear in Master and Commander and Jaws. It was a capstan shanty sung on homeward bound journeys. The lines “we’ll rant and we’ll roar like true British sailors, we’ll rant and we’ll roar along the salt seas,” might as well have been a battle cry. The verse “we’ll drink and be jolly and drown melancholy,” perfectly describes the sailor’s recipe for a bad mood.

This was a forecastle song telling a true story about whaling ship The Diamond which was lost at sea in 1819. Whaling in the age of sail was perhaps the most dangerous job a man could do. Sailors were required to kill the biggest creature on earth from a rowboat. The frost and winds and hard work alone were enough to make sure that only the toughest men signed up for the job.

Another whaling forecastle song. This one featured a sweet melody which reflected the melancholy of tired sailors. It told about coming home from a whaling trip and describes leaving behind the hardships of hunting for whales.

A halyard shanty about going around Cape Horn to whale. Rounding Cape Horn was one of the toughest tasks in the age of sail because of the strong and unfavorable winds in the area.There is some speculation as to what “blood red roses” is referring to. Some people say it’s a name for the Royal British marines who wore a red uniform. Others say it’s referring to whale’s blood on the surface of the water.

A forecastle ballad. Fiddler’s Green is sailors’ and fishermen’s version of heaven. A place where there is no work, where you have a mug of beer that refills itself, and there are pretty ladies dancing to a sound of fiddle that never ends. The idea of Fiddler’s Green was taken from an old Irish legend and adapted by sailors because at sea the dying did not have the chance to get properly anointed and therefore did not have the chance to enter Christian heaven.

A very sad capstan shanty (although it was probably sung more often in the forecastle). As with all shanties, there are many versions, but the basic story is that the sailor dreams about his love and in that instant he knows that she has died. There are versions where it’s the sailor’s girl that dreams about the sailor. Some versions are more elaborate and include sailors seeing red roses on his girl’s body as a symbol of blood, wet hair as a sign of drowning, and so on. In some versions after the death of a sailor the girl cuts her hair so that no other man will find her attractive.

A short haul shanty. Another popular shanty among modern shantymen. It contains, in my opinion, the best two lines of any shanty or sea song: “When I was a little boy my mother always told me…That if I did not kiss the girls, my lips would grow all moldy.” The rest of the song usually tells about the sailor’s adventures with women of different nationalities until he finds one that’s “just a daisy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment