Snow-bound

The sun that brief December day

Rose cheerless over hills of gray,

And, darkly circled, gave at noon

A sadder light than waning moon.

Slow tracing down the thickening sky

Its mute and ominous prophecy,

A portent seeming less than threat,

It sank from sight before it set.

A chill no coat, however stout,

Of homespun stuff could quite shut out,

A hard, dull bitterness of cold,

That checked, mid-vein, the circling race

Of life-blood in the sharpened face,

The coming of the snow-storm told.

The wind blew east; we heard the roar

Of Ocean on his wintry shore,

And felt the strong pulse throbbing there

Beat with low rhythm our inland air.

Meanwhile we did our nightly chores,

Brought in the wood from out the doors,

Littered the stalls, and from the mows

Raked down the herd's-grass for the cows;

Heard the horse whinnying for his corn;

And, sharply clashing horn on horn,

Impatient down the stanchion rows

The cattle shake their walnut bows;

While, peering from his early perch

Upon the scaffold's pole of birch,

The cock his crested helmet bent

And down his querulous challenge sent.

The World Transformed

Unwarmed by any sunset light

The gray day darkened into night,

A night made hoary with the swarm

And whirl-dance of the blinding storm,

As zigzag, wavering to and fro,

Crossed and recrossed the wingëd snow:

And ere the early bedtime came

The white drift piled the window-frame,

And through the glass the clothes-line posts

Looked in like tall and sheeted ghosts.

So all night long the storm roared on:

The morning broke without a sun;

In tiny spherule traced with lines

Of Nature's geometric signs,

In starry flake, and pellicle,

All day the hoary meteor fell;

And, when the second morning shone,

We looked upon a world unknown,

On nothing we could call our own.

Around the glistening wonder bent

The blue wall of the firmament,

No cloud above, no earth below, -

A universe of sky and snow!

The old familiar sights of ours

Took marvellous shapes; strange domes and towers

Rose up where sty or corn-crib stood,

Or garden-wall, or belt of wood;

A smooth white mound the brush-pile showed,

A fenceless drift what once was road;

The bridle-post an old man sat

With loose-flung coat and high cocked hat;

The well-curb had a Chinese roof;

And even the long sweep, high aloof,

In its slant spendor, seemed to tell

Of Pisa's leaning miracle.

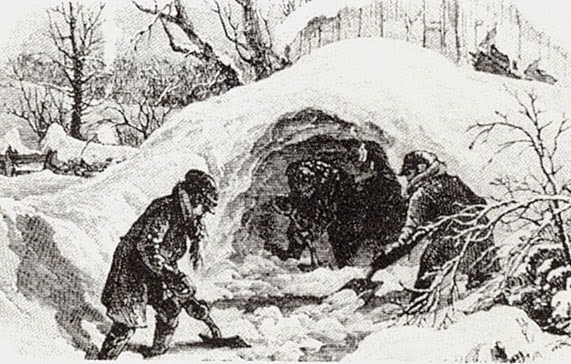

Father

A prompt, decisive man, no breath

Our father wasted: "Boys, a path!"

Well pleased (for when did farmer boy

Count such a summons less than joy?)

Our buskins on our feet we drew;

With mittened hands, and caps drawn low,

To guard our necks and ears from snow,

We cut the solid whiteness through.

And, where the drift was deepest, made

A tunnel walled and overlaid

With dazzling crystal: we had read

Of rare Aladdin's wondrous cave,

And to our own his name we gave,

With many a wish the luck were ours

To test his lamp's supernal powers.

We reached the barn with merry din,

And roused the prisoned brutes within.

The old horse thrust his long head out,

And grave with wonder gazed about;

The cock his lusty greeting said,

And forth his speckled harem led;

The oxen lashed their tails, and hooked,

And mild reproach of hunger looked;

The hornëd patriarch of the sheep,

Like Egypt's Amun roused from sleep,

Shook his sage head with gesture mute,

And emphasized with stamp of foot.

All day the gusty north-wind bore

The loosening drift its breath before;

Low circling round its southern zone,

The sun through dazzling snow-mist shone.

No church-bell lent its Christian tone

To the savage air, no social smoke

Curled over woods of snow-hung oak.

A solitude made more intense

By dreary-voicëd elements,

The shrieking of the mindless wind,

The moaning tree-boughs swaying blind,

And on the glass the unmeaning beat

Of ghostly finger-tips of sleet.

Beyond the circle of our hearth

No welcome sound of toil or mirth

Unbound the spell, and testified

Of human life and thought outside.

We minded that the sharpest ear

The buried brooklet could not hear,

The music of whose liquid lip

Had been to us companionship,

And, in our lonely life, had grown

To have an almost human tone.

As night drew on, and, from the crest

Of wooded knolls that ridged the west,

The sun, a snow-blown traveller, sank

From sight beneath the smothering bank,

We piled, with care, our nightly stack

Of wood against the chimney-back, --

The oaken log, green, huge, and thick,

And on its top the stout back-stick;

The knotty forestick laid apart,

And filled between with curious art

The ragged brush; then, hovering near,

We watched the first red blaze appear,

Heard the sharp crackle, caught the gleam

On whitewashed wall and sagging beam,

Until the old, rude-furnished room

Burst, flower-like, into rosy bloom;

While radiant with a mimic flame

Outside the sparkling drift became,

And through the bare-boughed lilac-tree

Our own warm hearth seemed blazing free.

The crane and pendent trammels showed,

The Turks' heads on the andirons glowed;

While childish fancy, prompt to tell

The meaning of the miracle,

Whispered the old rhyme: "Under the tree,

When fire outdoors burns merrily,

There the witches are making tea."

The moon above the eastern wood

Shone at its full; the hill-range stood

Transfigured in the silver flood,

Its blown snows flashing cold and keen,

Dead white, save where some sharp ravine

Took shadow, or the sombre green

Of hemlocks turned to pitchy black

Against the whiteness at their back.

For such a world and such a night

Most fitting that unwarming light,

Which only seemd where'er it fell

To make the coldness visible.

Firelight

Shut in from all the world without,

We sat the clean-winged hearth about,

Content to let the north-wind roar

In baffled rage at pane and door,

While the red logs before us beat

The frost-line back with tropic heat;

And ever, when a louder blast

Shook beam and rafter as it passed,

The merrier up its roaring draught

The great throat of the chimney laughed;

The house-dog on his paws outspread

Laid to the fire his drowsy head,

The cat's dark silhouette on the wall

A couchant tiger's seemed to fall;

And, for the winter fireside meet,

Between the andirons' straddling feet,

The mug of cider simmered slow,

The apples sputtered in a row,

And, close at hand, the basket stood

With nuts from brown October's wood.

What matter how the night behaved?

What matter how the north-wind raved?

Blow high, blow low, not all its snow

Could quench our hearth-fire's ruddy glow.

O Time and Change! -- with hair as gray

As was my sire's that winter day,

How strange it seems with so much gone,

Of life and love, to still live on!

Ah, brother! only I and thou

Are left of all that circle now, --

The dear home faces whereupon

That fitful firelight paled and shone.

Henceforward, listen as we will,

The voices of that hearth are still;

Look where we may, the wide earth o'er,

Those lighted faces smile no more.

We tread the paths their feet have worn,

We sit beneath their orchard trees,

We hear, like them, the hum of bees

And rustle of the bladed corn;

We turn the pages that they read,

Their written words we linger o'er.

But in the sun they cast no shade,

No voice is heard, no sign is made,

No step is on the conscious floor!

Yet love will dream, and Faith will trust

(Since He who knows our need is just),

That somehow, somewhere, meet we must.

Alas for him who never sees

The stars shine through his cypress-trees!

Who, hopeless, lays his dead away,

Nor looks to see the breaking day

Across the mourful marbles play!

Who hath not learned, in hours of faith,

The truth to flesh and sense unknown,

That Life is ever lord of Death,

And Love can never lose its own!

We sped the time with stories old,

Wrought puzzles out, and riddles told,

Or stammered from our school-book lore

"The Chief of Gambia's golden shore."

How often since, when all the land

Was clay in Slavery's shaping hand,

As if a far-blown trumpet stirred

The languorous sin-sick air, I heard:

"Does not the voice of reason cry,

Claim the first right which Nature gave,

From the red scourge of bondage to fly,

Nor deign to live a burdened slave!"

Our father rode again his ride

On Memphremagog's wooded side;

Sat down again to moose and samp

In trapper's hut and Indian camp;

Lived o'er the old idyllic ease

Beneath St. François' hemlock-trees;

Again for him the moonlight shone

On Norman cap and bodiced zone;

Again he heard the violin play

Which led the village dance away,

And mingled in its merry whirl

The grandam and the laughing girl.

Or, nearer home, our steps he led

Where Salisbury's level marshes spread

Mile-wide as flied the laden bee;

Where merry mowers, hale and strong,

Swept, scythe on scythe, their swaths along

The low green prairies of the sea.

We shared the fishing off Boar's Head,

And round the rocky Isles of Shoals

The hake-broil on the drift-wood coals;

The chowder on the sand-beach made,

Dipped by the hungry, steaming hot,

With spoons of clam-shell from the pot.

We heard the tales of witchcraft old,

And dream and sign and marvel told

To sleepy listeners as they lay

Stretched idly on the salted hay,

Adrift along the winding shores,

When favoring breezes deigned to blow

The square sail of the gundelow

And idle lay the useless oars.

Mother

Our mother, while she turned her wheel

Or run the new-knit stocking-heel,

Told how the Indian hordes came down

At midnight on Concheco town,

And how her own great-uncle bore

His cruel scalp-mark to fourscore.

Recalling, in her fitting phrase,

So rich and picturesque and free

(The common unrhymed poetry

Of simple life and country ways),

The story of her early days, --

She made us welcome to her home;

Old hearths grew wide to give us room;

We stole with her a frightened look

At the gray wizard's conjuring-book,

The fame whereof went far and wide

Through all the simple country side;

We heard the hawks at twilight play,

The boat-horn on Piscataqua,

The loon's weird laughter far away;

We fished her little trout-brook, knew

What flowers in wood and meadow grew,

What sunny hillsides autumn-brown

She climbed to shake the ripe nuts down,

Saw where in sheltered cove and bay,

The ducks' black squadron anchored lay,

And heard the wild-geese calling loud

Beneath the gray November cloud.

Then, haply, with a look more grave,

And soberer tone, some tale she gave

From painful Sewel's ancient tome,

Beloved in every Quaker home,

Of faith fire-winged by martyrdom,

Or Chalkley's Journal, old and quaint, --

Gentlest of skippers, rare sea-saint! --

Who, when the dreary calms prevailed,

And water-butt and bread-cask failed,

And cruel, hungry eyes pursued

His portly presence, mad for food,

With dark hints muttered under breath

Of casting lots for life or death,

Offered, if Heaven withheld supplies,

To be himself the sacrifice.

Then, suddenly, as if to save

The good man from his living grave,

A ripple on the water grew,

A school of porpoise flashed in view.

"Take, eat," he said, "and be content;

These fishes in my stead are sent

By Him who gave the tangled ram

To spare the child of Abraham."

Uncle

Our uncle, innocent of books,

Was rich in lore of fields and brooks,

The ancient teachers never dumb

Of Nature's unhoused lyceum.

In moons and tides and weather wise,

He read the clouds as prophecies,

And foul or fair could well divine,

By many an occult hint and sign,

Holding the cunning-warded keys

To all the woodcraft mysteries;

Himself to Nature's heart so near

That all her voices in his ear

Of beast or bird had meanings clear,

Like Apollonius of old,

Who knew the tales the sparrows told,

Or Hermes, who interpreted

What the sage cranes of Nilus said;

A simple, guileless, childlike man,

Content to live where life began;

Strong only on his native grounds,

The little world of sights and sounds

Whose girdle was the parish bounds,

Whereof his fondly partial pride

The common features magnified,

As Surrey hills to mountains grew

In White of Selborne's loving view, --

He told how teal and loon he shot,

And how the eagle's eggs he got,

The feats on pond and river done,

The prodigies of rod and gun;

Till, warming with the tales he told,

Forgotten was the outside cold,

The bitter wind unheeded blew,

From ripening corn the pigeons flew,

The partridge drummed i' the wood, the mink

Went fishing down the river-brink.

The woodchuck, like a hermit gray,

Peered from the doorway of his cell;

The muskrat plied the mason's trade,

And tier by tier his mud-walls laid;

And from the shagbark overhead

The grizzled squirrel dropped his shell.

Aunt

Next, the dear aunt, whose smile of cheer

And voice in dreams I see and hear, --

The sweetest woman ever Fate

Perverse denied a household mate,

Who, lonely, homeless, not the less

Found peace in love's unselfishness,

And welcome wheresoe'er she went,

A calm and gracious element,

Whose presence seemed the sweet income

And womanly atmosphere of home, --

Called up her girlhood memories,

The huskings and the apple-bees,

The sleigh-rides and the summer sails,

Weaving through all the poor details

And homespuun warp of circumstance

A golden woof-thread of romance.

For well she kept her genial mood

And simple faith of maidenhood;

Before her still a cloud-land lay,

The mirage loomed across her way;

The morning dew, that dries so soon

With others, glistened at her noon;

Through years of toil and soil and care,

From glossy tress to thin gray hair,

All unprofaned she held apart

The virgin fancies of the heart.

Be shame to him of woman born

Who hath for such but thought of scorn.

Sister

There, too, our elder sister plied

Her evening task the stand beside;

A full, rich nature, free to trust,

Truthful and almost sternly just,

Impulsive, earnest, prompt to act,

And make her generous thought a fact,

Keeping with many a light disguise

The secret of self-sacrifice.

O heart sore-tried! thou hast the best

That Heaven itself coud give thee, -- rest,

Rest from all bitter thoughts and things!

How many a poor one's blessing went

With thee beneath the low green tent

Whose curtain never outward swings!

As one who held herself a part

Of all she saw, and let her heart

Against the household bosom lean,

Upon the motley-braided mat

Our yougest and our dearest sat,

Lifting her large, sweet, asking eyes,

Now bathed in the unfading green

And holy peace of Paradise.

Oh, looking from some heavenly hill,

Or from the shade of saintly palms,

Or silver reach of river calms,

Do those large eyes behold me still?

With me one little year ago: --

The chill weight of the winter snow

For months upon her grave has lain;

And now, when summer south-winds blow

And brier and harebell bloom again,

I tread the pleasant paths we trod,

I see the violet-sprinkled sod

Whereon she leaned, too frail and weak

The hillside flowers she loved to seek,

Yet following me where'er I went

With dark eyes full of love's content.

The birds are glad; the brier-rose fills

The air with sweetness; all the hills

Stretch green to June's unclouded sky;

But still I wait with ear and eye,

For something gone which should be nigh,

A loss in all familiar things,

In flower that blooms, and bird that sings.

And yet, dear heart! remembering thee,

Am I not richer than of old?

Safe in thy immortality,

What change can reach the wealth I hold?

What chnce can mar the pearl and gold

Thy love hath left in trust with me?

And while in late life's late afternoon,

Where cool and long the shadows grow,

I walk to meet the night that soon

Shall shape and shadow overflow,

I cannot feel that thou art far,

Since near at need the angels are;

And when the sunset gates unbar,

Shall I not see thee waiting stand,

And, white against the evening star,

The welcome of thy beckoning hand?

The School Master

Brisk wielder of the birch and rule,

The master of the local school

Held at the fire his favored place,

Its warm glow lit a laughing face

Fresh-hued and fair, where scarce appeared

The uncertain prophecy of beard.

He teased the mitten-blinded cat,

Played cross-pins on my uncle's hat,

Sang songs, and told us what befalls

In classic Dartmouth's college halls.

Born the wild Northern hills among,

From whence his yeoman father wrung

By patient toil subsistence scant,

Not competence and yet not want,

He early gained the power to pay

His cheerful, self-reliant way;

Could doff at ease his scholar's gown

To peddle wares from town to town;

Or through the long vacation's reach

In lonely lowland districts teach,

Where all the droll experience found

At stranger hearths in boarding round,

The moonlit skater's keen delight,

The sleigh-drive through the frosty night,

The rustic party, with its rough

Accompaniment of blind-man's-buff,

And whirling-plate, and forfeits paid,

His winter task a pastime made.

Happy the snow-locked homes wherein

He tuned his merry violin,

Or played the athlete in the barn,

Or held the good dame's winding-yarn,

Or mirth-provoking versions told

Of classic legends rare and old,

Wherein the scenes of Greece and Rome

Had all the commonplace of home,

And little seemed at best the odds

'Twixt Yankee pedlers and old gods;

Where Pindus-born Arachthus took

The guise of any grist-mill brok,

And dread Olympus at his will

Became a huckleberry hill.

A careless boy that night he seemed;

But at his desk he had the look

And air of one who wisely schemed,

And hostage from the future took

In trained thought and lore of book.

Large-brained, clear-eyed, of such as he

Shall Freedom's young apostles be,

Who, following in War's bloody trail,

Shall every lingering wrong assail;

All chains from limb and spirit strike,

Uplift the black and white alike;

Scatter before their swift advance

The darkness and the ignorance,

The pride, the lust, the squalid sloth,

Which nurtured Treason's monstrous growth,

Made murder pastime, and the hell

Of prison-torture possible;

The cruel lie of caste refute,

Old forms remould, and substitute

For Slavery's lash the freeman's will,

For blind routine, wise-handed skill;

A school-house plant on every hill,

Stretching in radiate nerve-lines thence

The quick wires of intelligence;

Till North and South together brought

Shall own the same electric thought,

In peace a common flag salute,

And, side by side in labor's free

And unresentful revalry,

Harvest the fields wherein they fought.

The Prophetess

Another guest that winter night

Flashed back from lustrous eyes the light.

Unmarked by time, and yet not young,

The honeyed music of her tongue

And words of meekness scarcely told

A nature passionate and bold,

Strong, self-concentred, spurning guide,

Its milder features dwarded beside

Her unbent will's majestic pride.

She sat among us, at the test,

A not unfeared, half-welcome guest,

Rebuking with her cultured phrase

Our homeliness of words and ways.

A certain pard-like, treacherous grace

Swayed the lithe limbs and dropped the lash,

Lent the white teeth their dazzling flash;

And under low brows, black with night,

Rayed out at times a dangerous light;

The sharp heat-lightnings of her face

Presaging ill to him whom Fate

Condemned to share her love or hate.

A woman tropical, intense

In thought and act, in soul and sense,

She blended in a like degree

The vixen and the devotee,

Revealing with each freak of feint

The temper of Petruchio's Kate,

The raptures of Siena's saint.

Her tapering hand and rounded wrist

Had facile power to form a fist;

The warm, dark languish of her eyes

Was never safe from wrath's surprise.

Brows saintly calm and lips devout

Knew every change of scowl and pout;

And the sweet voice had notes more high

And shrill for social battle-cry.

Since then what old cathedral town

Has missed her pilgrim staff and gown,

What convent-gate has held its lock

Against the challenge of her knock!

Through Smyrna's plague-hushed thoroughfares,

Up sea-set Malta's rocky stair,

Gray olive slopes of hills that hem

Thy tombs and shrines, Jerusalem,

Or startling on her desert throne

The crazy Queen of Lebanon

With claims fantastic as her own,

Her tireless feet have held their way;

And still, unrestful. bowed, and gray,

She watches under Eastern skies,

With hope each day renewed and fresh,

The Lord's quick coming in the flesh,

Whereof she dreams and prophecies!

Where'er her troubled path may be,

The Lord's sweet pity with her go!

The outward wayward life we see,

The hidden springs we may not know.

Nor is it given us to discern

What threads the fatal sisters spun,

Through what ancestral years has run

The sorrow with the woman born,

What forged her cruel chain of moods,

What set her feet in solitudes,

And held the love within her mute,

What mingled madness in the blood

A life-long discord and annoy,

Water of tears with oil of joy,

And hid within the folded bud

Peversities of flower and fruit.

It is not ours to separate

The tangled skien of will and fate,

To show what metes and bounds should stand

Upon the soul's debatable land,

And between choice and Providence

Divide the circle of events;

But He who knows our frame is just,

Merciful and compassionate,

And full of sweet assurances

And hope for all the language is,

That He remembereth we are dust!

Last Firelights

At last the great logs, crumbling low,

Sent out a dull and duller glow,

The bull's-eye watch that hung in view,

Ticking its weary circuit through,

Pointed with mutely warning sign

Its black hand to the hour of nine.

That sign the pleasant circle. broke:

My uncle ceased his pipe to smoke,

Knocked from its bowl the refuse gray

And laid it tenderly away;

Then roused himself to safely cover

The dull red brands with ashes over,

And while, with care, our mother laid

The work aside, her steps she stayed

One moment, seeking to express

Her grateful sense of happiness

For food and shelter, warmth and health,

And love's contentment more than wealth,

With simple wishes (not the weak,

Vain prayers which no fulfilment seek,

But such as warm the generous heart,

O'er-prompt to do with Heaven its part)

That none might lack, that bitter night,

For bread and clothing, warmth and light.

A'bed

Within our beds awhile we heard

The wind that round the gables roared,

With now and then a ruder shock,

Which made our very bedsteads rock.

We heard the loosened clapboards tost,

The board-nails snapping in the frost;

And on us, through the unplastered wall,

Felt the light sifted snow-flakes fall.

But sleep stole on, as sleep will do

When hearts are light and life is new;

Faint and more faint the murmurs grew,

Till in the summer-land of dreams

They softened to the sound of streams,

Low stir of leaves, and dip of oars,

And lapsing waves on quiet shores.

Morning

Next morn we wakened with the shout

Of merry voices high and clear;

And saw the teamsters drawing near

To break the drifted highways out.

Down the long hillside treading slow

We saw the half-buried oxen go,

Shaking the snow from heads uptost,

Their straining nostrils white with frost.

Before our door the stragglins train

Drew up, an added team to gain.

The elders threshed their hands a-cold,

Passed, with the cider-mug, their jokes

From lip to lip; the younger folks

Down the loose snow-banks, wrestling rolled,

Then toiled again the cavalcade

O'er windy hill, through clogged ravine,

And woodland paths that wound between

Low drooping pine-boughs winter-weighed.

From every barn a team afoot,

At every house a new recruit,

Where, drawn by Nature's subtlest law,

Haply the watchful young men saw

Sweet doorway pictures of the curls

And curious eyes of merry girls,

Lifting their hands in mock defence

Against the snow-ball's compliments,

And reading in each missive tost

The charm with Eden never lost.

The Doctor

We heard once more the sleigh-bells' sound;

And, following where the teamsters led,

The wise old Doctor went his round,

Just pausing at our door to say,

In the brief autocratic way

Of one who, prompt at Duty's call

Was free to urge her claim on all,

That some poor neighbor sick abed

At night our mother's aid would need.

For, one in generous thought and deed

What mattered in the sufferer's sight

The Quaker matron's inward light,

The Doctor's mail of Calvin's creed?

All hearts confess the saints elect

Who, twain in faith, in love agree,

And melt not in an acid sect

The Christian pearl of charity!

A Week Later

So days went on: a week had passed

Since the great world was heard from last.

The Almanac we studied o'er,

Read and reread our little store

Of books and pamphlets, scarce a score;

One harmless novel, mostly hid

From younger eyes, a book forbid,

And poetry (or good or bad,

A single book was all we had),

Where Ellwood's meek, drab-skirted Muse,

A stranger to the heathen Nine,

Sang, with a somewhat nasal whine,

The wars of David and the Jews.

At last the flourndering carrier bore

The village paper to our door.

Lo! broadening outward as we read,

To warmer zones the horizon spread;

In panoramic length unrolled

We saw the marvels that it told.

Before us passed the painted Creeks,

And daft McGregor on his raids

In Costa Rica's everglades.

And up Taygetos winding slow

Rode Ypsilanti's Mainote Greeks,

A Turk's head at each saddle-bow!

Welcome to us its week-old news,

Its corner for the rustic Muse

Its monthly gauge of snow and rain,

Its record, mingling in a breath

The wedding bell and dirge of death:

Jest, anecdote, and love-lorn tale,

The latest culprit sent to jail;

Its hue and cry of stolen and lost,

Its vendue sales and goods at cost,

And traffic calling loud for gain.

We felt the stir of hall and street,

The pulse of life that round us beat;

The chill embargo of the snow

Was melted in the genial glow;

Wide swung again our ice-locked door,

And all the world was ours once more!

Echoes of the Past

Clasp, Angel of the backword look

And folded wings of ashen gray

And voice of echoes far away,

The brazen covers of thy book;

The weird palimpsest old and vast,

Wherein thou hid'st the spectral past;

Where, closely mingling, pale and glow

The characters of joy and woe;

The monographs of outlived years,

Or smile-illumed or dim with tears,

Green hills of life that slope to death,

And haunts of home, whose vistaed trees

Shade off to mournful cypresses,

With the white amaranths underneath.

Even while I look, I can but heed

The restless sands' incessant fall,

Importunate hours that hours succeed

Each clamorous with its own sharp need,

And duty keeping pace with all.

Shut down and clasp with heavy lids;

I hear again the voice that bids

The dreamer leave his dream midway

For larger hopes and graver fears:

Life greatens in these later years,

The century's aloe flowers to-day!

Yet, haply, in some lull of life,

Some Truce of God which breaks its strife,

The wordling's eyes shall gather dew,

Dreaming in throngful city ways

Of winter joys his boyhood knew;

And dear and early friends -- the few

Who yet remain -- shall pause to view

These Flemish pictures of old days;

Sit with me by the homestead hearth

And stretch the hands of memory forth

To warm them at the wood-fire's blaze!

And thanks untraced to lips unknown

Shall greet me like the odors blown

From unseen meadows newly mown,

Or lilies floating in some pond,

Wood-fringed, the wayside gaze beyond;

The traveller owns the grateful sense

Of sweetness near, he knows not whence,

And, pausing takes with forehead bare

The benediction of the air.

- John Greenleaf Whittier

*subtitles added by R.E. Slater

The poem takes place in what is today known as the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead, which still stands in Haverhill, Massachusetts.[1] The poem chronicles a rural New England family as a snowstorm rages outside for three days. Stuck in their home for a week, the family members exchange stories by their roaring fire.

Overview

Composition and publication history

John Greenleaf Whittier, author ofSnow-Bound, pictured in 1859

Whittier began the poem originally as a personal gift to his niece Elizabeth as a method of remembering the family.

[2] Nevertheless, he told publisher

James Thomas Fields about it, referring to it as "a homely picture of old New England homes".

[2] Snow-Bound was first published as a book-length poem on February 17, 1866.

[3]

Response

Snow-Bound was financially successful, much to Whittier's surprise.

[4] By the summer after its first publication, sales had reached 20,000, earning Whittier royalties of ten cents per copy. He ultimately collected $10,000 for it.

[5] Its popularity also led to the home depicted in the poem being preserved as a museum in 1892.

[6]

The first important critical response to Snow-Bound came from James Russell Lowell. Published in the North American Review, the review emphasized the poem as a record of a vanishing era. "It describes scenes and manners which the rapid changes of our national habits will soon have made as remote from us as if they were foreign or ancient," he wrote. "Already are the railroads displacing the companionable cheer of crackling walnut with the dogged self-complacency and sullen virtue of anthracite."[7] The poem was second in popularity only to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The Song of Hiawatha and was published well into the twentieth century. Though it remains in many common anthologies today, it is not as widely read as it once was.[6]

Analysis

The poem attempts to make the ideal past retrievable.[8] By the time it was published, homes like the Whittier family homestead were examples of the fading rural past of the United States.[6] The use of storytelling by the fireplace was a metaphor against modernity in a post-Civil War United States, without acknowledging any of the specific forces modernizing the country.[9] The raging snowstorm also suggests impending death, which is combated against through the family's nostalgic memories.[10] Scholar Angela Sorby suggests the poem focuses on whiteness and its definition, ultimately signaling a vision of a biracial America after the Civil War.[11]

*

* * * * * * * * * * *

Biography of John Greenleaf Whittier

An American poet and editor, John Greenleaf Whittier was born December 17, 1807, in Haverhill, Massachusetts. The son of two devout Quakers, he grew up on the family farm and had little formal schooling. His first published poem, "The Exile's Departure," was published in William Lloyd Garrison's Newburyport Free Press in 1826. He then attended Haverhill Academy from 1827 to 1828, supporting himself as a shoemaker and schoolteacher. By the time he was twenty, he had published enough verse to bring him to the attention of editors and readers in the antislavery cause. A Quaker devoted to social causes and reform, Whittier worked passionately for a series of abolitionist newspapers and magazines. In Boston, he edited American Manufacturer and Essex Gazette before becoming editor of the important New England Weekly Review. Whittier was active in his support of National Republican candidates; he was a delegate in 1831 to the national Republican Convention in support of Henry Clay, and he himself ran unsuccessfully for Congress the following year.

His first book, Legends of New England in Prose and Verse, was published in 1831; from then until the Civil War, he wrote essays and articles as well as poems, almost all of which were concerned with abolition. In 1833 he wrote Justice and Expedience urging immediate abolition. In 1834 he was elected as a Whig for one term to the Massachusetts legislature; mobbed and stoned in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1835. He moved in 1836 to Amesbury, Massachusetts, where he worked for the American Anti-Slavery Society. During his tenure as editor of the Pennsylvania Freeman, in May 1838, the paper's offices burned to the ground and were sacked during the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall by a mob.

Whittier founded the antislavery Liberty party in 1840 and ran for Congress in 1842. In the mid-1850s he began to work for the formation of the Republican party; he supported presidential candidacy of John C. Frémont in 1856. He helped to found Atlantic Monthly in 1857. Although Whittier was close friends with Elizabeth Lloyd Howell and considered marrying her, in 1859 he decided against it.

While Whittier's critics never considered him to be a great poet, they thought him a nobel and kind man whose verse gave unique expression to ideas they valued. The Civil War inspired the famous poem, "Barbara Frietchie," but the important change in his work came after the war. From 1865 until his death in 1892, Whittier wrote of religion, nature, and rural life; he became the most popular Fireside poets.

In 1866 he published his most popular work, Snow-Bound, which sold 20,000 copies. In the early 1880s, he formed close friendships with Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields. For his seventieth birthday dinner in 1877, Ralph Waldo Emerson,

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Mark Twain, Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell, and William Dean Howells attended. He died at Hampton Falls, New Hampshire, on September 7, 1892.

A Selected Bibliography

Poetry

Legends of New England in Prose and Verse (1831)

Moll Pitcher (1832)

Justice and Expediency (1833)

Poems (1838)

Lays of My Home (1843)

The Panorama (1846)

Voices of Freedom (1846)

Poems by John G. Whittier (1849)

Songs of Labor (1850)

The Chapel of the Hermits (1853)

Poetical Works (1857)

Home Ballads (1860)

In War Time (1864)

Snow-Bound (1866)

The Tent on the Beach (1867)

Among the Hills (1869)

Miriam and Other Poems (1871)

Hazel-Blossoms (1875)

The Vision of Echard (1878)

St. Gregory's Guest (1886)

At Sundown (1890)

The Complete Poetical Works of John Greenleaf Whittier (1894)

Prose

Leaves from Margaret Smith's Journal (1849)

Old Portraits and Modern Sketches (1850)

Literary Recreations and Miscellanies (1854)